The World is Losing another Historic Generation

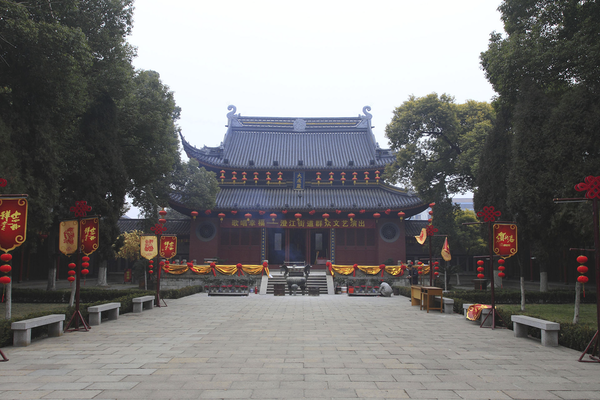

Temple of Confucius of Jiangyin, Wuxi, Jiangsu. Photo by Zhangzhugang. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Every day, little by little, one of the world’s largest and most important historic generations is passing away— the last generation to have grown up in China before the communist takeover in 1949. These individuals were born between 1919 and 1937, right before the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War, and were raised in what we might loosely call traditional China. Yes, China was surely modernizing during the years 1919-1949, but traditional Chinese culture retreated only slowly and was still pervasive in 1949, even in foreign-influenced coastal cities like Shanghai. Dense bastions of traditional practices remained in education, the judiciary, and government bureaucracies, as well as in family structure and social relations in general. Students and young people shaped by this environment were in touch with a very ancient Chinese system of values, with all its cultural beauty and social flaws.

After 1949 the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) launched an active campaign to eradicate traditional values they regarded as “feudal thinking,” extending their long-standing hostility against the Confucian worldview to national educational policy. Things got much worse during the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976 when fanatical anti-traditional hysteria generated a decade of state-tolerated anarchic violence and contempt by Red Guard youth groups directed against “feudal” and “bourgeois” values. The widespread physical destruction of artwork and cultural sites during those years was the most visible manifestation of a policy designed to root out traditional thinking tied to the pre-revolutionary past.

More recently the CCP has paid lip-service to the nation’s past culture by appropriating Confucius’s name for the vast network of international “Confucian Institutes” that project a positive image of communist China to the outside world. These institutes have little connection to China’s past; they are primarily centers of communist propaganda and recruitment of naïve, sympathetic foreign students. A Chinese ruling elite that tolerates corrupt communists and crony capitalists has no genuine interest in a state grounded in Confucian ethics. Instead they pick out the Confucian elements that reinforce communist rule, such as emphases on political loyalty and communalism.

Students coming of age in China today are acquainted with only those parts of classical Chinese art, literature, and philosophy that the CCP regards as useful for justifying its continued one-party dictatorship. Conversations with Chinese students reveal alarming gaps in their knowledge of China’s political and economic development before 1949. Disastrous events under communist rule like the failure of the Great Leap Forward and the resulting famine of 1959-1961 or the Tian An Men massacre of 1989 are “forbidden topics” beyond discussion or even mention in Chinese schools and universities, but that is a separate topic. This is not simply complaining about the habits and interests of today’s youth in China; these knowledge gaps are a deliberate product of the CCP’s Orwellian educational policy reaching back over many decades with the intent of allowing vast swathes of pre-communist history and culture to wither away.

These trends mean that as the last generation of individuals who grew up in, were educated, in, or were at least exposed to classical Chinese education and culture leave us, they will not be replaced. That human loss will be a bitter blow, perhaps the death blow, for a civilization with a 5,000 year pedigree. The surviving cultural remnants will be only those crumbs from the pre-communist past selected by the CCP for public presentations carefully managed by the party for its own purposes.

In a dangerous irony, this great reduction in the human cultural capital of pre-communist China comes at the same time the growth of Chinese economic, military, and political influence around the world makes international audiences more interested than ever before in understanding some of the deeper elements of Chinese culture.

If the outside world wants to understand China’s long history, traditional values, and cultural contributions in an intellectually honest way, we will have to get beyond the carefully controlled version of history being offered by the current communist government. We can help by doing two things. First, by maintaining open, honest, and critical scholarship of China’s long history at universities and research institutes around the world. That includes refusing to knuckle under to China’s frequent demands that we cooperate with their efforts to censor critical research produced by foreign-based scholars. Second, we can support the remaining outposts of Chinese culture that exist beyond the reach of the CCP, for example in Taiwan, where non-communist versions of China’s past, present, and future are on display every day.

We cannot prevent the passing away of China’s last generation from the pre-communist era, but we can do our part in helping to preserve the ancient culture they knew, so that it does not vanish completely with them.