The Cold War New and Old: Architectural Exchanges Beyond the West

Recent reports on Chinese and Russian involvement in infrastructural developments in Africa and the Middle East coined the phrase “New Cold War”. Yet when seen from the Global South, the continuities with the 20th century lie less in the confrontation with the West, and more in reviving the collaboration between the “Second” and the “Third” worlds. In my recent book Architecture in Global Socialism (Princeton University Press, 2020) I argue that architecture is a privileged lens to study multiple instances of such collaboration, and their institutional, technological, and personal continuities.

When commentators discuss China’s expanding involvement in Africa, they often point at its continuity with the Cold War period. This includes the “Eight Principles” of Chinese aid, announced by prime minister Zhou Enlaiin 1964 during his visit to Ghana, at the time of China’s widening ideological split with the Soviet Union. Less discussed is the fact that, in spite of this split, these principles closely echoed the tenets of Soviet technical assistance from which China had benefitted and which was under way in Ghana. Like China later, so the Soviet Union offered low-interest loans for the purchase of Soviet equipment, the transfer of technical knowledge to the local personnel, and assurances of mutual benefit and respect for the sovereignty of the newly independent state.

Above: Nikita Khrushchev and president Sukarno inspect the model of the National Stadium in Jakarta (Indonesia), 1960. R. I. Semergiev, K. P. Pchel'nikov, U. V. Raninskii, E. G. Shiriaevskaia, A. B. Saukke, N. N. Geidenreikh, I. Y. Yadrov, L. U. Gonchar, I. V. Kosnikova. Private archive of Igor Kashmadze. Courtesy of Mikhail Tsyganov.

In 1960s West Africa, the Soviet Union and its Eastern European satellites used technical assistance to promote socialist solidarity against the United States and Western Europe. Architects, planners, engineers, and construction companies from socialist countries were instrumental in the implementation of the socialist model of development in Ghana, Guinea, and Mali. It was based on industrialization, collectivization, wide distribution of welfare, and mass mobilization. Until today, many urban landscapes in West Africa bear witness to how local authorities and professionals drew on Soviet prefabrication technology, Hungarian and Polish planning methods, Yugoslav and Bulgarian construction materials, Romanian and East German standard designs, and manual laborers from across Eastern Europe.

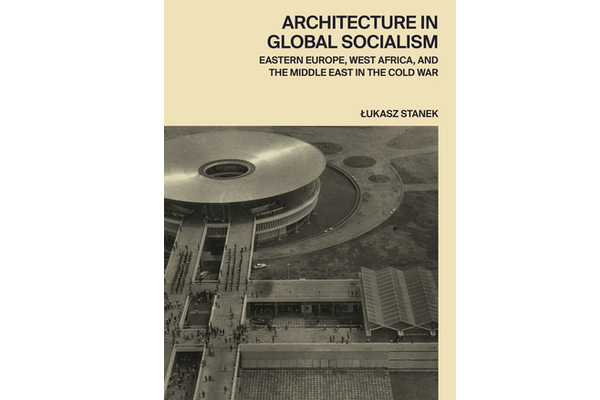

Above: International Trade Fair, Accra (Ghana), 1967. Ghana National Construction Corporation (GNCC), Vic Adegbite (chief architect), Jacek Chyrosz, Stanisław Rymaszewski (project architects). Photo by Jacek Chyrosz. Private archive of Jacek Chyrosz, Warsaw (Poland)

Some of these engagements were interrupted by regime changes, as it was the case in Ghana, when the socialist leader Kwame Nkrumah was toppled in 1966. But socialist or Marxist-Leninist regimes were not the only, and even not the main, destinations for Soviet and Eastern European architects and contractors. Their most sustained work, often straddling several decades, took place in countries which negotiated their position across the Cold War divisions, such as Syria under Hafez al-Assad, Iraq under Abd al-Karim Qasim and the regimes that followed, Houari Boumédiene’s Algeria, and Libya under Muammar Gaddafi. By the 1970s Eastern Europeans were invited to countries with elites openly hostile to socialism, such as Nigeria, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates.

Some countries in the Global South collaborated with Eastern Europe in order to obtain technology embargoed by the West. More often, they aimed at a stimulation of industrial development and at offsetting the hegemony of Western firms. Many of these transactions exploited the differences between the political economy of state socialism and the emerging global market of design and construction services. For example, state-socialist managers used the inconvertibility of Eastern European currencies to lower the costs of their services. In turn, barter agreements bypassed international financial markets when raw materials from Africa and Asia were exchanged for buildings and infrastructures constructed by components, technologies, and labor from socialist countries.

Above: State House Complex, Accra(Ghana), 1965. Ghana National Construction Corporation (GNCC), Vic Adegbite (chief architect), Witold Wojczyński, Jan Drużyński (project architects). Photo by Ł. Stanek, 2012.

The 1973 oil embargo was a game changer for Eastern European construction export. The profits from oil sales, deposited by Arab governments with Western financial institutions, were lent to socialist countries intent on modernizing their economies. Yet when the industrial leap expected from these investments did not materialize, Hungary, Poland, and East Germany struggled to repay huge loans in foreign currencies. Debt repayment became a key objective for the stimulation of export from many Eastern European countries, in particular as the Soviet Union was increasingly unwilling to subsidize them with cheap oil and gas. Faced with the shrinking markets for their industrial products, Eastern Europeans boosted the export of design and construction services.

By the 1970s, the main destinations of this export were the booming oil-producing countries in North Africa and the Middle East. In Algeria, Libya, and Iraq, state-socialist enterprises constructed housing neighborhoods, schools, hospitals, and cultural centers, as well as industrial facilities and infrastructure, paid in convertible currencies or bartered for crude oil. Eastern Europeans also delivered master plans of Algiers, Tripoli, and Baghdad, and worked in architectural offices, planning administration, and universities in the region.

Above: Flagstaff House housing project, Accra(Ghana), 1963. Ghana National Construction Corporation (GNCC), Vic Adegbite (chief architect), Károly (Charles) Polónyi (design architect). Photo by Ł. Stanek, 2012.

These collaborations were as widespread as they were uneven. Under pressure of state and party leadership to produce revenue in convertible currencies, state-socialist enterprises were highly accommodating to the requests of their North African and Middle Eastern counterparts. In turn, the latter were often constrained by path-dependencies of Eastern European technologies already acquired.

Many would see such transactions as indicative of a shift in socialist regimes from ideology to pragmatism, if not cynicism. But a more complex picture emerges when these transactions are addressed through the lens of architecture, which spans not only economy and technology, but also includes questions of representation, identity, and everyday life.

While largely abandoning the discourse of socialist solidarity, Eastern European architects continued to speculate about the position in the world that they shared with Africans and Middle Easterners. In so doing, they aimed at identifying professional precedents useful for the tasks at hand. For example, the expertise of tackling rural underdevelopment, which had been long claimed by Central European architects as their professional obligation, provided specific planning tools in the agrarian countries of the Global South. In turn, the search for “national architecture” in the newly constituted states in Central Europe after World War I became useful when architects were commissioned to design spaces representing the independent countries in Africa and Asia.

Above: Municipality and Town Planning Department, Abu Dhabi(UAE), 1979-85. Bulgarproject (Bulgaria), Dimitar Bogdanov. Photo by Ł. Stanek, 2015.

During the Cold War, these exchanges were carefully recorded in North America and Western Europe. But after 1989, they were often forgotten by policy makers, professionals, and scholars in the West. By contrast, buildings, infrastructures, and industrial facilities co-produced by West Africans, Middle Easterners, and Eastern Europeans are still in use in the Global South, and master plans and building regulations are still being applied. Some of the modernist buildings are recognized as monuments to decolonization and independence, while others sit awkwardly in rapidly urbanizing cities.

Memories of collaboration with Eastern Europe are vivid among professionals, decision makers and, sometimes, users of these structures. They result in renewed engagements when, for example, Libyan authorities invite a Polish planning company to revisit its master plans for Libyan cities delivered during the socialist period. These memories speak more about the experience of collaboration that bypassed the West, and less about a Cold War confrontation, old or new.