The Cultural Constants of Contagion

Sometime during the year 541, a few rats found their way into Byzantium. Soon more would arrive in the city. Whether they came from ships unloading cargo in Constantinople’s bay, or overland in carts bringing goods from points further east, the rodents carried fleas harboring the Yersina pestis bacterium. Byzantium’s citizens, ruled over by the increasingly erratic Justinian, had heard accounts of the plague as it struck down other nations first. The historian Procopius, who was witness to the ensuing pestilence, writes in his History of the Wars that the resultant disease “seemed to move by fixed arrangement, and to tarry for a specified time in each country, casting its blight… spreading in either direction out to the ends of this world, as if fearing some corner of the earth might escape it.”

Known as Justinian’s Plague, the pandemic marked the first instance of the bubonic plague in Europe, almost a millennium before its more famous manifestation as the Medieval Black Death. William Rosen writes in Justinian’s Flea that while contagion was a feature of human life, before the sixth-century “none of them [had] ever swept across what amounted to the entire known world, ending tens of millions of lives, and stopping tens of millions more from ever being born.” By the pandemic’s end, epidemiologists estimate that perhaps a quarter of the known world’s population had perished.

There is something deep within our collective unconscious that dimly apprehends these past traumas. The accounts of a historian like Procopius sound familiar to us; echoes of such horror in everything from the skeleton masks of Halloween, the morbid aesthetic of the gothic, and the horror movies of pandemic–from the clinical Contagion and Outbreak to the fantastical The Walking Dead and 28 Days Later. We so fearfully thrill to narratives of apocalypse, that when faced with our own pandemic there is something almost uncanny about it. For the past several months a few Western observers nervously read reports about the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. More people paid attention as cases emerged in Italy. Shades of Procopius, who reflected that “at first the deaths were a little more than the normal, then the mortality rose still higher, and afterwards the tale of dead reached five thousand each day, and again it even came to ten thousand and still more than that.” Today almost every nation in the European Union is affected by coronavirus, a majority of U.S. states, and every single continent save for Antarctica. Physicians have yet to fully ascertain the disease’s mortality rate, but thousands have already died, and contrary the obstinate denials from the president of the United States, Covid-19 clearly seems to be more than “just the flu.”

Those of us who work in the humanities have, for more than a generation, been loath to compare radically different time periods and cultures–and for good reason. There can be a flattening to human experience when we read the past as simply a mirror of our own lives. Yet plague is, in some ways, a type of cultural absolute zero, a shared experience of extremity that does seem to offer certain perennial themes that approach universality. For the first time in more than a century, since the Spanish Influenza outbreak of 1918, we collectively and globally face a pandemic that threatens to radically alter the lives of virtually everybody on the planet. It behooves us to converse with the dead. Much is alien about our forebears, but when we read accounts of pestilence raging through ancient cities, it’s hard not to hear echoes of our own increasingly frenzied push notifications.

There is a collection of morbid motifs which recur with epidemics–the initial disbelief, the governmental incompetence, hoarding of goods, desperate attempts at protection (including the embrace of superstition), social stigma and bigotry, social distancing and quarantine, and of course panic. In the pilfered N95 surgical masks there are echoes of the avian masks worn by Renaissance plague doctors; in the rosemary, sage, and thyme clutched by medieval peasants there are precursors of the Purell which we’re all desperately using (albeit the latter is certainly more effective). As different as those who lived before us may be, the null void which is the pandemic does display a certain universality in how people react to their circumstances, born necessarily from biology itself. For example, gallows humor is an inextricable and required aspect of human endurance, though it can also mark a dangerous denialism. Catharine Arnold writes in Pandemic 1918 that the in its earliest days, the Spanish flu was either denied or joked about. Arnold writes that “At the [Cape Town, South Africa] Opera House, a cough in the audience provided the actor on stage with an excellent opportunity to ad-lib. ‘Ha, the Spanish flu, I presume?’ The remark brought the house down.” However, she writes that “within days, that joke wasn’t funny anymore.”

Few emotions are as all encompassing, understandable, and universal as is panic. In the queasy feeling which a pandemic inculcates throughout a society there is a unity of experience across disparate time periods. Consider the language from The New York Evening Post in July of 1832 as they traced the inevitable arrival of a cholera epidemic into the city, where inhabitants of the metropolis fled “from the city, as we may suppose the inhabitants of Pompeii or Reggio fled from those devoted places.” Naturally hoarding is another predictable behavior, if often dangerous and self-defeating, as can be attested to anyone who has tried to buy hand sanitizer or toilet paper in the last week, or with the squirreling away of face masks which are currently needed by public health officials. Procopius again notes that in Byzantium, “it seemed a difficult and very notable thing to have sufficiency of bread or of anything else; so that with some of the sick it appeared that the end of life came about sooner than it should have come by reason of the lack of the necessities of life.”

This panic can metastasize into rank irrationalism, as pandemic often leads to the embrace of quack cures, or more disturbingly the promulgation of noxious hatreds. Philip Ziegler writes in The Black Death that during the pandemic of 1348, in France a “fashionable course of study” regarding the plague included “an ointment called ‘Black de Razes’” that was “on sale at apothecaries as a cure recommended for virtually any ailment.” Its effectiveness might be compared to the silver nitrate solutions hawked by televangelist Jim Bakker as a prophylactic against coronavirus. During the Black Death, fear was a convenient catalyst for old hatreds, as the plague justified antisemitic pogroms. By dint of both their isolation and the religious strictures that encouraged rigorous hygiene, medieval Jewish communities were sometimes spared the worst of the plague. This was interpreted by Christians as complicity in the pandemic, and so the Jews were made to suffer for their previous good fortune. John Kelly writes in The Great Mortality that antisemitism “bubbled up from the medieval Teutonic psyche,” where in Germany and other nations the religious cult of the Flagellants “believed the curse of the mortality could be lifted through self-abuse of the flesh and slaying Jews.”

Xenophobia similarly marked more modern pandemics. In the first four years of the twentieth-century, San Francisco saw America’s only prolonged outbreak of bubonic plague. Brought by ship into the city, where today a coronavirus contaminated cruise ship lingers off the bay, the plague broke out in Chinatown, leading to hundreds of deaths. Marilyn Chase explains in The Barbary Plague that “public health efforts… were handicapped by limited scientific knowledge and bedeviled by the twin demons of denial and discrimination.” Rather than offering treatment, Mayor James D. Phelan spread fear about the Chinese residents of the city, anticipating today’s talk of “foreign virus.” He called them “a constant menace to the public health,” while ironically exacerbating the outbreak by dint of his policy. Meanwhile, California governor Henry Gage simply denied the existence of the plague at all, fearing more that the economy would be harmed then that his fellow citizens were dying.

If there is a commonality to the recurring themes that mark pandemics throughout history, it’s because of the physical reality of the ailment. Covid-19 can’t be explained away, can’t be ignored, can’t be obscured, can’t be denied. It can’t be tweeted out of existence. It turns out that internet memes aren’t the same thing as viruses. We may yet discover that in a “post-reality” world, reality has a way of coming to collect its debts.

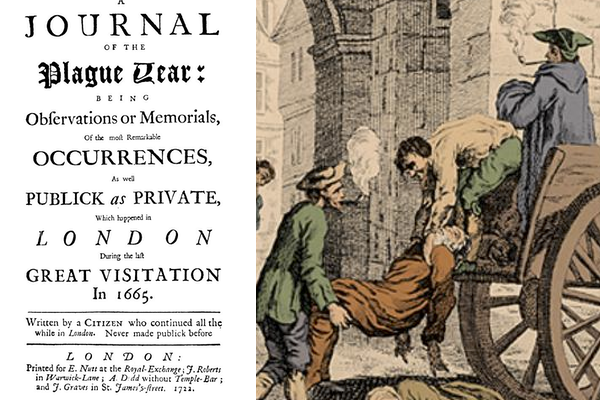

An important reminder, however; for all of the uncertainty, panic, and horror which pandemics spread, there is also the acknowledgment, at least among some, of our shared affliction, our collective ailment, our common humanity. Within a plague there are fears both rational and irrational, there are prejudices and panics, there is selfishness, cruelty, and hatred. But there is also kindness, and the opportunity for kindness. The story of pandemics contains flagellants, but also selfless physicians and nurses; it includes the shunning of whole groups of people but the relief of treatment as well. We’ve never faced something like the coronavirus in the contemporary Western world, but we’d do well to remember something strangely hopeful that Daniel Defoe observed in his quasi-fictional A Journal of the Plague Year, 1666 when the last of the major bubonic outbreaks killed a fifth of London’s population: “a close conversing with Death, or the Diseases that threaten Death, would scum off the Gall from our Tempers, remove the Animosities among us, and bring us to see with differing Eyes, than those which we look’d on Things with before.”