Pandemic Exposes Vulnerabilities of Workers on Farms

On my most recent trip for groceries during this COVID-19 self-isolation, I noticed that the grocery store had established new procedures. The store was carefully cleaned and the shopping cart handles had been wiped down with disinfectant. There was a reduced limit to how many shoppers could be in the store at one time. There were markers on the floor denoting six feet, the distance that reduces the chances of contagion. And as the cashier scanned my milk and apples, there was a plexiglass barrier protecting him from airborne pathogens. These measures were all assuring and reasonable. The government had deemed the grocery store (and by extension, the worker) essential, and his labor was keeping our food supply chain operational. Considering the health risk he was taking by being there, it seemed the least that could be done.

After all, food is essential, and as long as it is available in a time of emergency, we feel greater security. The workers who make this possible deserve any and all protections at their disposal. Yet those at the beginning of the supply chain—people who do farm work—are the least protected workers in the country, and the vulnerability and insecurity we are experiencing now is something they deal with on a regular basis. They are at greater risk for exposure to dangerous diseases due to their living and employment conditions, are less likely to afford missing work or seeking health care when sick, and, because of their racial background and precarious legal status, face additional stress and discrimination when requesting medical services.

According to the National Center for Farmworker Health, there are approximately 2 to 3 million migratory and seasonal agricultural workers in the United States today, not including their spouses and children. The majority (73%) of all agricultural workers are foreign born, most of them (69%) born in Mexico, and close to half of the foreign-born population of agricultural workers (40%) have spent 20 or more years living in the United States. The average hourly wage earned by an agricultural worker in 2011 and 2012, based on figures provided by the U.S. Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS), was $10.19. Only 14% of farmworkers in the NAWS reported being covered by employer-provided health insurance. 46% of those surveyed reported paying for health care services out-of-pocket during their last health care visit.

Farmworkers’ poor socioeconomic conditions, and the lack of broad legal protections and benefits providing improvements in their labor and civil rights, means that one of the nation’s most essential populations remains vulnerable during this crisis. Farmworkers’ vulnerability has potentially devastating consequences for all of us who depend on the food they supply. Various farmworker advocates and organizations recently released a statement calling for increased attention to the ongoing and emerging needs of the farmworker community, and the enactment of policy measures that protect and support all farmworkers. Among the pressing issues they raise are the fact that most farmworkers do not have the same safety nets that would permit them to miss work—like financial savings, paid sick leave, or unemployment compensation. Farmworker housing conditions, which are typically overcrowded and substandard, also pose a heightened risk for the transmission of infectious diseases. Although farmworkers may want to isolate themselves and their children from exposure to the virus, they have to work. Farmworker parents are thus increasingly forced to place their children in unsafe situations to provide alternative childcare during school closures. And, like many working-class families, most farmworkers do not have health insurance or the financial means and transportation to seek medical attention when they need it. In cases they do seek medical care, earlier studies on pandemic influenza and farmworkers found that they are likely to face significant cultural and language barriers to timely and adequate treatment, and discrimination and profiling. Under these circumstances, it is near impossible for farmworker families to prevent and treat COVID-19.

This is why the federal government has to do more to protect our nation’s farmworkers and include migrant families in any efforts to provide further safeguards and relief. In writing about federal intervention in farmworkers’ lives during the 1930s and 1940s, I discovered that the Farm Security Administration (FSA), under the U.S. Department of Agriculture, created a number of state-based Agricultural Workers Health Associations (AWHA), beginning in 1938, to guarantee all migratory farmworkers and their families access to quality medical care. The health plan’s principal objective was to serve low-income agricultural workers who could not obtain medical assistance from welfare agencies because of residency requirements or lack of funds. The FSA encouraged migrant workers to visit one of the associations’ participating clinics where they could receive treatment and secure a referral to a participating local physician for additional care.

The FSA’s health plan entitled farmworkers to full medical, surgical, hospital, and dental care, including coverage for medications, vaccinations, and any special diet requirements prescribed by the doctor. Patients were expected to pay as much as they could, but for the most part all expenses were billed to the corresponding AWHA, which the FSA subsidized. Conservative figures suggest that the FSA covered anywhere between 75,000 and 200,000 agricultural workers in its plans at any one time. By the early 1940s, the FSA had also set up migrant health clinics in about 250 key areas of farm labor concentration throughout the country, mostly as part of its labor camp program. In the FSA’s farm labor camps, migrants could consult with the nurse, who staffed the clinic daily and also lived in the camp. All of the FSA camps also had quarantine housing for those who required it.

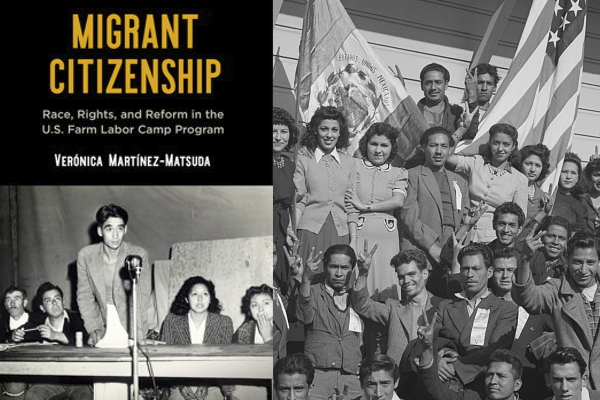

As my book Migrant Citizenship reveals, the FSA’s medical program existed at a time when farmworkers were deliberately excluded from all New Deal labor and social protections. Defying the broader conservative political forces of the time, the FSA intervened because it understood that farmworkers’ health was vital to the nation’s wellbeing. As one federal official warned the congressional Committee on the Interstate Migration of Destitute Citizens in 1940, “Contagious diseases are no respecters of social class or geographic boundary.”

A serious response to the public health crisis we face today cannot ignore farmworkers, including the more than half who are undocumented and in mixed-status families. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (“CARES Act”) promises to provide assistance to American workers, families, and businesses. Yet, the act specifically excludes “non-resident aliens.” The legislation fails to protect the lives of all people living and working in the United States. We must pressure our local and state governments to reject President Trump’s disregard for our nation’s farmworkers. These essential workers and valued community members must have full access to all testing, treatment, and relief afforded to others, and must be included in any plan to provide Medicare for all. Until they do, the food we bring home remains contaminated with injustice.