Minorities, Native Peoples, the Poor, and Infectious Diseases from Columbus to Coronavirus

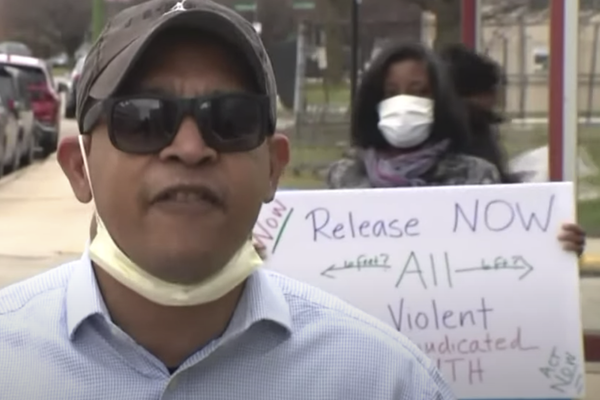

Protesters demand release of inmates from Cook County Jail, Chicago

An early April Washington Post article warned “the coronavirus is infecting and killing black Americans at an alarmingly high rate,” telling us what historians should have guessed. About the same time, Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo of New York stated that “it always seems that the poorest people pay the highest price. Why is that? Whatever the situation is.” He noted that African Americans and Latinos were suffering and dying at greater rates than whites, and in some areas the disproportion was even greater than in New York--e.g., in Louisiana and Michigan, where African Americans comprised 70 and 40 percent of the respective coronavirus deaths though being only 32 and 14 percent respectively of the states’ populations. Moreover, it is likely that minority and poor coronavirus deaths were (and are)--like deaths from other infectious diseases--under-reported. Other articles have dealt with how dangerous the coronavirus is for U. S. prisoners, the homeless, and undocumented immigrants and refugees, all disproportionately numbered with minorities.

Outside of the USA the poor and minorities are also most threatened by COVID-19. The PBS Newshour profiled the Moria camp on the island of Lesbos. The Newshour correspondent indicated that the refugee camp was originally intended for 3,000 people, but there are now about 20,000 refugees crowded together in tents and hovels, with no running water. One refugee told him, “The people are scared, because, when the coronavirus come here, nobody can save their life.” A recent Foreign Affairs article on the misguided nature of President Trump’s “America First” policy stated that “COVID-19 could soon overwhelm [the self-governing Palestinian territory] Gaza’s anemic health system,” with its almost two million densely-packed people. The essay quotes a former State Department officer who notes that Middle-East refugees and others “are particularly vulnerable to the virus, because in overcrowded camps, distancing is impossible, and residents lack access to information, soap, and clean water.”

While U.S. citizens are understandably mainly concerned about domestic coronavirus threats and inconveniences, the title of still another article, “In Scramble for Coronavirus Supplies, Rich Countries Push Poor Aside,” should remind us that not only do poor individuals often get shafted, but so too do poor nations. And of this writing, the worst effects of the pandemic are most likely still ahead for many poor nations; the United Nations World Food Program indicated that the figure of 135 million people at risk of food shortage could nearly double due to COVID-19.

Although people had died of infectious diseases long before the beginning of the Roman Empire, a noticeable increase in the Americas began with Columbus’s landing on the Haitian portion of Hispaniola. As one history of Native Americans (James Wilson’s The Earth Shall Weep, 1999) states it, “The peoples of the western hemisphere in 1492 . . . . had almost no resistance to a whole range of diseases, from the common cold and measles to smallpox and bubonic plague,” and “scholars now believe that epidemics of European diseases were far more devastating to native people than had previously been imagined.”

In his 2008 essay “The Conquerors,” historian Edmund Morgan indicates that diseases and other causes reduced Hispaniola’s native Arawak Indians from at least 100,000 in 1492 to about 200 in 1542. To take their place the Spanish imported slaves from Africa. Wilson cites one source that indicates “there were almost a hundred epidemics and pandemics of European diseases among Native Americans between the first contact and the beginning of the twentieth century.”

Although U. S. slaves, overwhelmingly in southern states, certainly suffered from infectious diseases prior to the Civil War, the war and the Reconstruction Era created new medical difficulties for freed slaves. Federal, state, and local officials pointed fingers at each other for inadequately providing aid to ex-slaves, and “this confusion created an institutional vacuum that left ex-slaves defenceless against disease outbreaks, and their situation was further exacerbated by freedpeople's nebulous political and economic status.” And, of course, from the late-nineteenth century to the present, African-Americans have continued to deal with racist effects that have had adverse effects on their health.

In her recent These Truths: A History of the United States, Jill Lepore presents statistics that should startle the minds of any citizens believing in a history that minimizes the role of Native Americans and African Americans: “Between 1500 and 1800, roughly two and a half million Europeans moved to the Americas [note: not just the USA]; they carried twelve million Africans there by force; and as many as fifty million Native Americans died, chiefly of disease.” And she adds that “the isolation of the Americas from the rest of the world, for hundreds of millions of years, meant that diseases to which Europeans and Africans had built up immunities over millennia were entirely new to the native peoples of the Americas.” Among them were “smallpox, measles, diphtheria, trachoma, whooping cough, chicken pox, bubonic plague, malaria, typhoid fever, yellow fever, dengue fever, scarlet fever, amoebic dysentery, and influenza.”

In her Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-82, Elizabeth Fenn explains that in 1774 when smallpox struck Philadelphia, its chief victims were “the children of poor people.” She also noted how, as Ben Franklin indicated, that inoculation for a tradesman’s large family was “more money than he can well spare.” Nor could “artisans nor the working poor” afford to take the time off work that accompanied the inoculation process. For these and other reasons, immunity was concentrated “among the well-to-do.”

Later infectious disease outbreaks often revealed similar disproportional effects on the poor and/or minorities. For example, the smallpox epidemic of 1837–38 hit hard many of the Native American agricultural villages along the Missouri River. Later in the century after most Indians had been moved to reservations, other diseases such as tuberculosis, pneumonia, measles, and influenza killed them off in large numbers.

John Barry’s highly-praised The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, dealing with the 1918-1919 outbreak that killed at least fifty million worldwide, states what history so often confirms about epidemics and pandemics--“the poor died in larger numbers than the rich.”

Of the many millions of global deaths in this deadly pandemic, less than two percent (about 675,000) occurred in the USA. Similarly, the poor and indigenous peoples in other countries have also frequently been more decimated by infectious diseases.

Not long after Columbus first landed in Hispanola, the forces of Spaniard Hernán Cortés in 1521 captured Tenochtitlan, an Aztec city of 200,000. His main ally? A smallpox epidemic that in a single year reduced the city’s population by 40 percent.

In Muscovite Russia, Russian military forces and officials swept some 3,000 miles eastward across Siberia (an area larger than the USA) in less than three quarters of a century, reaching the Pacific Ocean by the mid-seventeenth century. In subjugating various Siberian indigenous peoples the conquerors were often aided by epidemics like smallpox and measles, which sometimes wiped out more than half a people’s population.

In the late eighteenth century, several expeditions led by James Cook helped establish British control over Australia and New Zealand. Onehistory of smallpox recounts that “fifteen months after the settlers’ arrival in Sydney in 1788, an appalling epidemic of smallpox attacked the unprotected aborigines of Australia, as the native Americans had been attacked nearly two centuries earlier.” Another account sums up the effect of infectious diseases on the Māoris of New Zealand, the nation’s largest indigenous group. “From around 100,000 in 1769, the Māori population had declined by 10–30% by 1840. This was largely due to introduced diseases . . . . Between 1840 and 1891 disease and social and economic changes had serious negative effects on Māori health, and a significant impact on the population.” In that half century, “the Māori population may have halved. ”

The natives of Africa, most of whom fell under European control in the late nineteenth century, suffered in a similar manner. One of the best accounts of some of the injustices of the continent’s imperialism comes from Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. “As with the decimation of the American Indians, disease killed many more Congolese than did bullets. Europeans and the Afro-Arab slave-traders brought to the interior of the Congo many diseases previously not known there. . . . Smallpox had been endemic in parts of coastal Africa for centuries, but the great population movements of the imperial age spread the illness throughout the interior, leaving village after village full of dead bodies.” He added, “Epidemics almost always take a drastically higher and more rapid toll among the malnourished and the traumatized.”

Thus, for many centuries before our present coronavirus pandemic, and in many parts of the world, indigenous people, minorities, and the poor have suffered disproportionately from infectious diseases. Because of less of almost everything--immunity, adequate food and water, money, housing, leisure, medical access, etc.--epidemics have proportionately killed a larger percentage of the disadvantaged. And so it is today in our present crisis.

While some of us have adequate housing and money, can work from home, maintain social distancing, and worry about how we are going to entertain ourselves and/or our children, the disadvantaged have few such luxuries. (See here for one case in a hard-hit Detroit community.) Increasingly, they are unemployed or must risk exposure on public transportation as they travel to essential jobs like being low-paid EMT or nursing-home workers. And then there are all those who are homeless, often crowded together on streets at night, or in prison, or in low-cost public housing, where social distancing is more difficult. And the poorer among us must worry about how they are going to pay for food, rent, mortgage payments, and medical care, which because of their poverty will be inadequate. Moreover, many of the poor are more likely to suffer from some of the pre-existing conditions that make contracting the coronavirus more deadly. Decisions made this week by Republican governors like Georgia’s Brian Kemp reflect both a refusal to support policies that would help poor and mostly minority workers to stay home, but also undercut the political power of black elected officials in communities hard-hit by the virus like Atlanta.

In most of the world outside China, Europe, and the United States, poverty is more widespread and the worst effects of the pandemic are yet likely to soar. Take, for example, India, with its 1.3 billion people, where the government instituted a “lockdown” for at least three weeks beginning on 25 March. As a result, “India's poorest . . . now face penury and deprivation.”

Good history requires empathy and imagination. So too does understanding how the coronavirus affects not just us or our family and friends, but also other people, including all the less advantaged, whether in the USA or abroad.