Yes, John Wilkes Booth did Speak Those Notorious Words At Lincoln's Last Speech

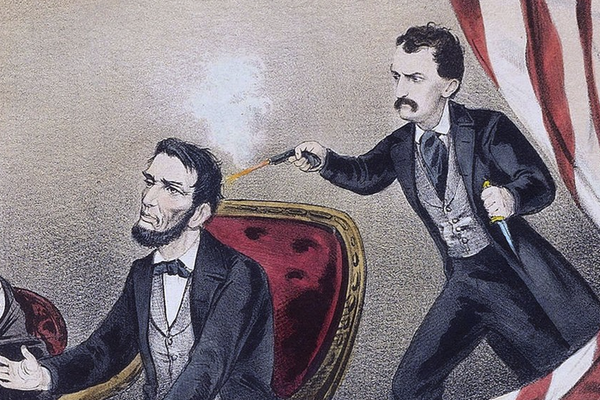

Ever since Abraham Lincoln’s law partner and close friend William H. Herndon completed his book Herndon’s Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life in 1888 and published it in 1889 and 1890, American historians have reprised this Shakespearean scene, found on page 579 of Herndon’s third volume, as prologue to the tragic murder of our national hero by the Shakespearean actor John Wilkes Booth:

Frederick Stone, counsel for Harold after Booth’s death, is the authority for the statement that the occasion for Lincoln’s assassination was the sentiment expressed by the President in a speech delivered from the steps of the White House on the night of April 11, when he said: “If universal amnesty is granted to the insurgents I cannot see how I can avoid exacting in return universal suffrage, or at least suffrage on the basis of intelligence and military service.” Booth was standing before Mr. Lincoln on the outskirts of the crowd. “That means nigger citizenship,” he said to Harold by his side. “Now, by God! I’ll put him through.”

(Herndon misspelled the surname of David Herold, Booth’s assassination plot co-conspirator. Lincoln delivered his speech from an open window of the White House, not from the steps.)

Besides being consistent with Booth’s dramatic style, that declaration established Booth’s motive for murdering Lincoln and confirmed the date and the context of his determination to commit the crime of the century.

I read Herndon’s Lincoln when I was in elementary school, at age 10 or 11, being a juvenile bookworm with adult library privileges and a member of an Illinois family with a modest Lincoln legacy (my mother’s heirlooms included a mechanical pencil and a beaded coin purse, presents Lincoln gave to my great-great-grandfather, John Wallis Ewing). More than 65 years later, I still recall that poignant passage with visceral revulsion.

Publication of the quotation did not originate with Herndon (or with his collaborator, Jesse W. Weik), but as Herndon wrote in his preface, “Use has been made of the views and recollections of other persons, but only those known to be truthful and trustworthy.”

George Alfred Townsend, who had covered the assassination, trials and executions of those who aided Booth’s conspiracy as Washington correspondent for the New York World, was the reporter who first published Booth’s malediction, in this passage from his historical romance novel, Katy of Catoctin, in November 1886:

President Lincoln addressed the people from his mansion in Washington on the night of April 11th, saying:

“If universal amnesty is granted to the insurgents, I can not see how I can avoid exacting in return universal suffrage, or at least suffrage on the basis of intelligence and military service.”

There were then hundreds of thousands of colored soldiery, and the insurgent President had demanded the right to arm the slaves.

Booth was standing before Mr. Lincoln on the outskirts of the large assemblage. “That means nigger citizenship,” he said to little Herold, by his side. “Now, by God! I’ll put him through.”*

Townsend’s footnote reads:

*Frederick Stone, counsel for Herold after Booth’s death, told the author that this was the occasion of the deliberate murder being resolved upon by Booth, and in the words above.

I counted 62 other places in the novel where Townsend inserted similar footnotes to add factual historical and literary references that framed his fictional narrative. They begin in his chapter titled “John Brown Executed,” where Booth, as a member of the Richmond Grays militia, witnessed the hanging. The sample dozen that I checked all proved to be accurate.

Louis J. Weichmann, the prosecution’s principal witness in the trial of Booth’s accomplices, cited that passage and two others from Townsend’s book as credible evidence of the conspirators’ intentions and exploits in his authoritative 1898-99 compilation, A True History of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln and of the Conspiracy of 1865. Collector Floyd E. Risvold purchased Weichmann’s unpublished manuscript and supporting documents from Weichmann’s descendants, and published them in 1975.

In his preface to Katy of Catoctin, Townsend, “who knew Booth personally,” explained that he had postponed writing the book “because too many actors in the tragedy still lived,” which suggests to me that his story cleaved as close to the truth as he thought documented facts and decorum allowed.

Besides, the author’s stock of materials, made complete by visits and searches of nineteen years, required the interpretation of his own eye and hand.

He felt that, while to have written this book earlier would have been to speak too harshly and too narrowly of some agents in the crime, to postpone the composition longer would have been to remand it to mere antiquarian literature.

Five months after his book appeared, Townsend included Booth’s oath in a nationally syndicated newspaper feature article, “The Death of Lincoln,” but with the footnote sentence incorporated into the text. It seems likely to me that more readers learned of it from their newspapers than from the novel.

Ever since, nearly every major historian of the event has quoted Booth’s execration. For example, on page 852 of Battle Cry of Freedom, James McPherson wrote:

At least one listener interpreted this speech as moving Lincoln closer to the Radical Republicans. “That means nigger citizenship,” snarled John Wilkes Booth to a companion.” “Now, by God, I’ll put him through. That is the last speech he will ever make.”

As an example of its persistence in American lore, the eminent Lincoln scholar Harold Holzer chronicled, augmented, and embellished that anecdote on pages 78 and 79 of his 2004 book for young readers, The President is Shot! The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln:

One person in the audience that night who recognized at once the importance of Lincoln’s words was none other than John Wilkes Booth.

“That means nigger citizenship,” Booth hissed to his friend Lewis Powell. “Now, by God, I will put him through.”

Imagine my surprise when I learned that since 2015 Holzer has denied the authenticity of the words he and Herndon and McPherson and dozens of other biographers and historians had quoted. Holzer presented his reasons (but not whatever had prompted him to change his mind) in a Lincoln Lecture sponsored by the National Archives to mark the 150th anniversary of the assassination (on-line at www.youtube.com/watch?v=OCdIwwkqImU).

Holzer doubted that the quote could be authentic because Townsend had not included it in his 1865 nonfiction book, The Life, Crime, and Capture of John Wilkes Booth and the Pursuit, Trial and Execution of His Accomplices. But Townsend had not known about it in 1865.

In his eulogy for Stone in the October 25, 1899, Baltimore Sun, Townsend wrote:

About 1870, soon after Judge Stone’s second marriage, I drove from Washington city to his residence, without any letter to him or previous acquaintance, to sound him upon the information he received from David Herold, who was with Wilkes Booth upon his flight. I had suspected that he became Herold’s counsel to close that person’s mouth upon the circumstances of the flight, during which some or several persons had probably fed and expedited the assassins. From his friendly and humane character, Judge Stone also acted on behalf of Mrs. Surratt, in both cases probably without charge. If I had formed any idea that his region was unlike the rest of the world, from the associations of that tragedy, they were immediately dispersed by Mr. Stone’s consideration. He said that some persons were still living who were sensitive upon that question and until they died he could not freely communicate what he knew, but he would bear the matter in mind, and if the future ever allowed him to speak he might do so….

After a dozen to fifteen years I wrote to him that I thought it was due the literary concerns of history to give me that information, and that I would have to proceed without it in my compositions if he did not impart it. He then wrote to me to meet him at the junction from Annapolis on his way home from court upon Friday and stay over Sunday with him at La Plata.

Stone — a prominent Maryland judge and former Congressional representative — was alive when Townsend published the Booth quote. He surely would have protested had Townsend misrepresented his statement.

Beyond those reasons for treating Stone’s information as true, I doubt that anyone who has reflected on the two men’s reputations can believe that Herold (“a weak, simple-minded youth without much force of character . . . like a boy only eleven years of age,” according to Weichmann) could have made up such a story, or that Stone would have.

In my opinion, the information Stone supplied to Townsend, which Townsend published in Katy of Catoctin in 1886 and in “The Death of Lincoln,” in 1887, is credible. Stone’s client Herold quoted Booth as having muttered — or maybe, as Holzer wrote in 2004, “hissed” — during Lincoln’s April 11 speech, “That means nigger citizenship. Now, by God! I will run him through.” Historians should not hesitate to teach it.