US Congress could Use Reconstruction-Era Civil Rights Powers to Protect Black Lives Today

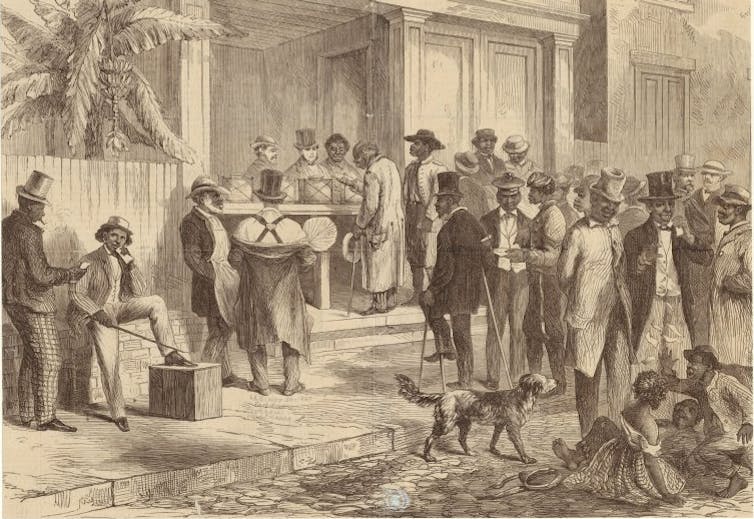

African Americans voting in New Orleans in 1867. 19th century illustration via New York Public Library Digital Collection via Wikimedia Commons

The man in the White House doesn’t believe in racial equality. He is erratic, vain, and conspiratorial. In a speech to celebrate George Washington’s birthday, the president mentioned himself 200 times in 60 minutes. The House of Representatives voted to impeach him, but the president’s powerful son-in-law helped him to escape removal from office.

The year is 1868. The president is Andrew Johnson, the southern Democrat who succeeded Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was installed in the White House following Lincoln’s assassination on Good Friday 1865, only a week after Robert E Lee had surrendered Confederate forces in the American civil war.

In his first months as president, Johnson had appeared to be a disaster for the cause of black civil rights. He pardoned Confederate soldiers, supported white supremacist state governments, and vetoed funding for the Freedmen’s Bureau, which had been established to provide food, healthcare, education, and job security to newly emancipated slaves.

Emboldened by this anti-civil rights president, southern state governments implemented “black codes” which were designed to return African Americans as close to the position of slavery as possible. Vague crimes such as “vagrancy” – effectively, unemployment – were used to arrest African Americans who were not seen as sufficiently industrious or subservient.

While such laws often didn’t mention race explicitly, they were used in practice to target African Americans. In some states, a sheriff could imprison anyone who could not prove that they were employed, and then the prisons could contract their labour to pay for the costs of incarceration. State governments profited handsomely.

In spite of these initial setbacks, Johnson’s presidency was also marked by some of the most important civil rights achievements for a century. This was possible because Congress governed without the president. Congress was controlled by the pro-civil rights Republican Party, which was determined not to allow the menace in the White House to undermine the victory for black equal citizenship that had just be won in the civil war. These same Reconstruction-era powers could be used today by Congress to protect the rights of African Americans.

Civil rights advanced

Under the US constitution, the president cannot block legislation which commands two-thirds support of Congress. Congressional Republicans took advantage of this power to pass laws such as the Civil Rights Act of 1866. The president also has no role in the constitutional amendment process. The most powerful and enduring legal legacy of this period of congressional governance was three amendments to the constitution known as the “Reconstruction amendments”.

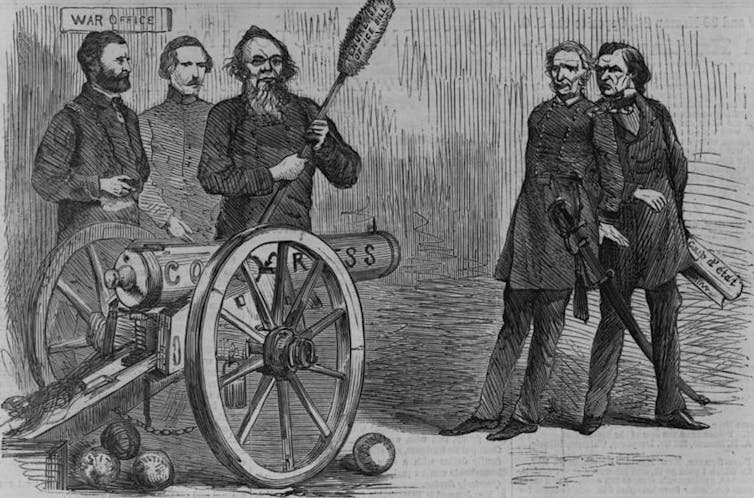

President Johnson did not have the support of the Republican-led Congress. "The Situation", a Harper's Weekly editorial cartoon from 1868 via Wikimedia Commons

Ratified within five years of each other, these three amendments fundamentally changed property relations, the balance of power in the state-federal relationship, and the meaning of and eligibility for US citizenship. The 13th amendment abolished slavery in 1865 (it was passed before Lincoln’s assassination but ratified during Johnson’s presidency). The 14th amendment, ratified in 1868, addressed the citizenship rights of the ex-slaves. In 1870, the 15th amendment explicitly forbade racial discrimination in voting.

Read more: How black grassroots politics led to the 14th Amendment and black citizenship

Promise of the 14th amendment

The 14th amendment was really more like four or five constitutional amendments rolled into one. The first three sections provided a constitutional basis for civil rights legislation. They guaranteed citizenship to every person born in the US, ensured equal due process, and guaranteed equal protection under the law for all Americans, regardless of which state they inhabited.

The 14th amendment also provided a constitutional basis for attacking white supremacist political power. It barred former officials who had supported the Confederacy from holding political office without Congress’s approval. It forbade the federal government from using US taxpayer money to finance Confederate war debt or to provide financial compensation for the abolition of slavery, a key difference from abolition in the British Empire in which slave-holders were compensated. Instead, Congress passed laws to compensate ex-slaves through land-redistribution – although, this programme of reparations was ultimately incomplete and underfunded.

And it implicitly guaranteed black suffrage by empowering Congress with the ability to reduce the congressional representation of any state which failed to provide universal suffrage to all men over the age of 21.

The 14th amendment was limited in its scope by the Supreme Court in the late 19th century, permitting Jim Crow segregation that deprived African Americans of their brief experience of equal citizenship. It was not until the 1950s that the Supreme Court began to roll back its earlier, narrow interpretation of the powerful amendment, for the benefit of African Americans.

An under-used tool

The powers of the Reconstruction-era amendments are still held by Congress today – but their radical potential has been underestimated.

Due to a 2013 Supreme Court decision which disabled the most powerful enforcement section of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, American jurisdictions can shape voting rules without federal approval, known as preclearance. This means states can introduce in punitive voter ID laws, engage in over-zealous voter purges, and close polling stations in predominantly black areas with much greater ease. The recent experience of voters in Georgia shows the harmful consequences of a weak Voting Rights Act.

But, the 14th amendment is an unexplored tool to correct the Supreme Court’s disastrous decision. If the Democratic-led House of Representatives were serious about protecting black voting rights ahead of the 2020 election, it could use its constitutional powers to strip states which try to disenfranchise racial minorities of their congressional representation.

The US is plagued by a constitution which contains numerous anti-democratic elements. These include a malapportioned Senate and electoral college which grossly under-represent urban populations, an overly powerful Supreme Court, and a federal system which militates against universal rights and welfare by failing to set national standards in the face of state opposition.

But as I argue in my own recent research, there are seeds of democracy in the constitution too, especially in the three Reconstruction amendments. Johnson was constrained by a pro-civil rights Congress. The legacy of that Reconstruction era has been under-deployed by Congress today, which seemingly lacks the political will to govern on behalf of racial minorities.

Richard Johnson, Lecturer in US Politics and International Relations, Lancaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.