After Those Cruel Wars Were Over: Lessons from Two Economic Recoveries

As the U.S. unemployment rate hovers around the awful level of 15 percent, it is tempting to see the current crisis as a second coming of the Great Depression. But this analogy may go too far, to the extent that it leads people to believe that unemployment will still be high and production low for many years to come; that because 2020 is like 1930, 2029 will be like 1939. If widely accepted, this narrative projecting a Great Depression of the 2020s may itself inhibit recovery, by discouraging spending and investment.

A more optimistic and useful set of analogies, we believe, is provided by the experiences of the United States after the World Wars. In the latter half of 1918, the U.S. economy suffered two severe shocks. First there was the end of the Great War, which meant the demobilization of the armed forces and the termination of the production of munitions. And then, as we all now know, the U.S. was hit by the Spanish flu pandemic. An economic contraction began around August 1918, even before the end of the war and the start of the deadlier second wave of the flu. But it ended and an expansion began in March of 1919, making the postwar recession one of the shortest since the Civil War. Then, in 1920, there was another sharp contraction, made worse by the Federal Reserve’s decision to adopt a tight money policy to squeeze out the ongoing inflation, a legacy of wartime monetary policies. But by mid-1921, the U.S. economy was growing again, and, despite some weaknesses and short downturns, enjoyed close to a decade of solid growth. The story was similar at the end of World War II. A contraction began in early 1945, even before VE Day, but it ended before the end of the year. Once again the economy began to expand after a relatively brief contraction.

These are not isolated examples. Throughout history, nations and communities have demonstrated remarkably resilience, in the wake of disasters, including those that caused extreme dislocation and mass death. For example, Germany and Japan both made astonishing recoveries in the 1950s, despite the enormous destruction and loss of life they had suffered during World War II. Remarkable post-crisis rebounds were also common in earlier eras. Indeed, in the mid-nineteenth century, the great economist and philosopher John Stuart Mill wrote that “… what has so often excited wonder, the great rapidity with which countries recover from a state of devastation; the disappearance, in a short time, of all traces of the mischiefs done by earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, and the ravages of war. An enemy lays waste a country by fire and sword, and destroys or carries away nearly all the moveable wealth existing in it: all the inhabitants are ruined, and yet in a few years after, everything is much as it was before."

The reason, as Mill explained, was that much of the durable capital, and the “skill and knowledge of the people”—what we would now call the human capital—survived, so they could be set to work again after these crises. And the same will be true for us. Automobile companies will still know how to make automobiles, hairdressers and barbers will still know how to give haircuts, kindergarten teachers will still know how to educate young people, and surgeons and nurses will still know how to do hip replacements. Moreover, pent-up demand will help speed recovery. People will continue to want automobiles, haircuts, and … many other things.

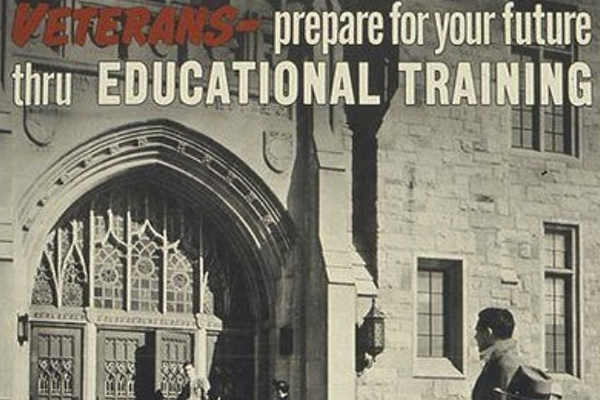

Although history suggests the likelihood of a relatively rapid recovery, this doesn’t mean, of course, that there is nothing that government can do to promote this. For example, during World War II, Congress acted to correct the previous neglect of war veterans, by enacting the G.I. Bill. That legislation provided unemployment benefits, which, thanks to the brevity of the postwar recession, were used less than expected. But veterans did take great advantage of the G.I. Bill’s education benefits. They helped many veterans whose education had been disrupted by the war, and, moreover, provided additional investments in human capital, above and beyond those available before the war. Today, with millions of our young women and men having their educations disrupted by the pandemic, governments can aid recovery and longer-run prosperity, by making new investments in education and human capital. These might be beneficially combined with additional investments in infrastructure, including those focused on environmental sustainability, which would further enhance the future prospects of our young people.

Another lesson from the world wars is that even though we have to spend enormous sums on crash industrial programs to overcome the crisis, we don’t need to turn a blind eye to corruption and profiteering. During World War I, special excess-profits taxes were imposed to deal with these problems, but they were too little and too late to prevent widespread public discontent with profiteering. This was remembered by Congress and the leaders of the World War II mobilization, who created a strict regime of high income taxes, windfall profits taxes, price and profit controls, and audits and investigations, to minimize malfeasance and boost public morale. Today, we may not require such a heavy hand of regulation as the one that prevailed during World War II, but there is plenty of room for Congress to do more to investigate and remedy current problems with profiteering, corruption, mismanagement, and inequality. So far, the Trump Administration has resisted sharing information about billions of dollars’ worth of emergency loans and other pandemic-related public outlays. To boost transparency and public trust, Congress may need to do more to support a new version of something like the Truman Committee, which provided useful public oversight of the military-industrial mobilization for World War II.

Of course, it is possible that this crisis will prove to be harder to overcome than we expect. Vaccine programs may run into unforeseen difficulties; U.S. and world leaders may fail to make good policy choices; and pandemic disease may prove to be so unmanageable as to suppress employment and investment for many years to come. We don’t dismiss entirely this dangerous possibility of a Great Depression of the 2020s, but we suggest that history offers considerable hope that it can be avoided. Human ingenuity and resilience, if adequately supported by competent governance, should allow us to overcome this crisis in months, instead of many years. We should embrace a cautious optimism, while demanding that our leaders take steps to promote, rather than inhibit, recovery and long-run prosperity.