Better Than Silence: The Need for Memorials to the Manhattan Project

Seventy-five years ago, the United States detonated the first atomic bomb in Alamogordo, New Mexico. Given the enormity of that event, and the ensuing swift conclusion of World War II, it would be reasonable to expect a substantial physical manifestation of the place’s importance. A park, perhaps, or a museum.

Instead the site of the Trinity Test is closed. Yes, it was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1975. But people can only visit on two days a year -- one in spring and one in fall. Visitors may drive to the site to see the nearly barren landscape and the distant hills that, before dawn on July 16, 1945, were illuminated brighter than one hundred suns. A black stone marker stands about twelve feet tall with its dull brass plaque, surrounded by security fences and a vast expanse of sky. That is all.

When the bomb detonated, atop its 100-foot steel tower, it heated the sandy soil below into glass. The tower itself was vaporized. Should you find a piece of the glass, keeping it is against the law. No artifacts, please.

If Alamogordo’s minimalized memorial indicates America’s uncertain relationship with the bomb’s history, then the city two hundred and fifty miles away where the weapon was built reveals an even deeper ambivalence. In a time when monuments are under nationwide debate, Los Alamos may set the standard for what not to do.

Aug. 11 will be the three-year anniversary of the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, VA. Its purported aim was to prevent removal of a statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. The real intent surfaced when the rally turned violent, with many people injured and one woman killed.

Since then the debate over monuments has intensified. Cities as different as Lexington, KY, Baltimore and New Orleans removed statues of Confederate leaders. Protestors weighed in too, for example tearing down the statue of Confederate president Jefferson Davis in Richmond. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, 114 Confederate statues have come down since Charlottesville.

In other words, America is having a heated argument about how to represent its past. From Christopher Columbus forward, some public historic symbols have become controversial. The bomb is no exception.

Granted, this nation is fully capable of memorializing painful or complex times. A visitor to Pearl Harbor National Memorial can stand at the window, and see the USS Arizona sitting right there on the bottom. The most casual tourist at Gettysburg can easily find a pamphlet detailing how many boys died in Pickett’s Charge – on both sides. Even above the beaches of Normandy, there is no flinching from the brutal reality of what liberating France required. The cost of valor is tallied in tombstones.

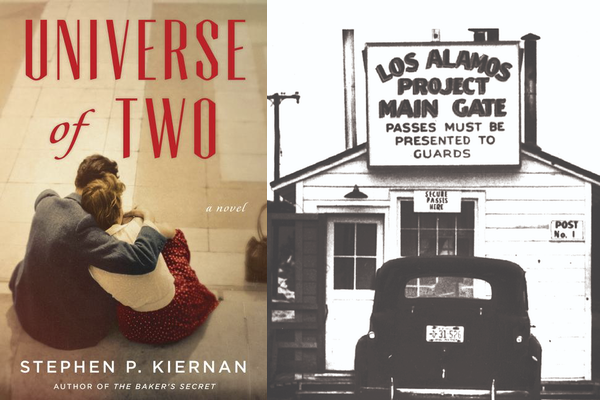

Los Alamos is not the same. I went there to do research for my book Universe of Two. All those years after the Trinity test, I had not expected a stone wall.

The book is a novel, loosely based on the life of Harvard-trained mathematician Charles B. Fisk. He worked on the Manhattan Project, first within the Metallurgy Department at the University of Chicago, and then in Los Alamos. After the war he received a full scholarship from Stanford University to get a PhD in physics.

Apparently the program’s emphasis on developing new bombs diminished his enthusiasm. Fisk dropped out after less than a semester, taking a part-time job with a company that repaired church organs. When he died in 1983, Fisk was considered one of the greatest cathedral organ builders ever. The company he founded continues to make premium instruments for colleges, universities and churches around the world.

I learned none of this from the two paid historians on staff at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. All they would do is confirm that Fisk had worked there, on the detonator team.

When I reached Los Alamos, I found a similar disinterest in disclosure. Such fundamental tools as maps – of the work sites, of the barracks’ locations -- were not available. I tried with the Historic Society, which directed me to the National Parks office, which was closed in the middle of the day – for several days.

I pressed on. A geologist whose job was to remediate radioactive areas loaned me maps he’d used to organize the various extraction sites. It was helpful for understanding the scale of the Project’s operation, but couldn’t tell me where Fisk might have lived. Ultimately I relied on the hand drawn maps in self-published memoirs by the wives of Manhattan Project scientists – hardly an exacting record.

To be fair, Los Alamos is home to the Bradford Science Museum, a clean place with enthusiastic displays. But it lacks even one mote of dust about the consciences of those who built the bomb, who questioned its moral fitness. Hundreds of project scientists repeatedly petitioned the Department of War, the State Department and the president, arguing that the bomb should be demonstrated, not used on civilians. You won’t find that information in the exhibits. If you search the museum’s digital document archive under the word petition, there are zero matches.

Los Alamos’ ambivalence about its history is perhaps most physically expressed at Fuller Lodge. In the 1930s, when the area was home to a rough-riding boys’ school, the lodge’s large wooden edifice, with a stone patio facing Ashley Pond, served as the campus center. After the U.S. government acquired the school and surrounding lands, Fuller Lodge continued to be the hub of activity: dances, speeches, concerts, dinners, plays.

But for those who notice subtleties, the history represented there is selective. Fuller Lodge bears a brass plaque declaring it to be on the National Historic Registry. Inside, Native American rugs hang on the walls. Local potters’ work sits in glass cabinets.

But the photos on the walls are revelatory in what they exclude: Here are schoolboys playing basketball. Here’s a graduating class. If there is a picture of Manhattan Project director Robert Oppenheimer, or any of the scientists who labored to build the bomb, it hangs somewhere out of sight.

Is this place special because it was a school? Or because thousands of scientists, engineers and technicians made incredible leaps in knowledge and technology there, harnessing the power of the atom as a tool of war that would change international relations forever? According to the photos, the school’s history wins.

For as long as mankind has warred, new technologies have been put swiftly to use: the trebuchet, gunpowder, the airplane. But each of these tools, in general, was aimed to defeat enemy combatants -- with the intention of sparing innocent civilians. Atomic bombs make no such distinction. They kill everyone within reach, the criminal and the child, the murderer and the monk. Creating the bomb was both a milestone achievement, and a profound expansion of the limits of warfare.

That is not to say that memorials about complex matters cannot exist. The Vietnam Memorial in Washington, DC is a stunning example, simultaneously questioning the war and honoring those who made the ultimate sacrifice. Likewise the 168 empty chairs in the plaza beside the Oklahoma City bombing memorial both symbolize the lives that were lost, and bear mute witness to the crime committed there. The endlessly falling water in the Ground Zero monument in New York City represents the countless tears shed by friends and families and a nation for people whose only error was in going to work on Sept. 11, 2001.

What might a proper memorial for the creation of the atomic bomb look like? If Japan can build the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, the artists and architectural geniuses of this nation can find a suitable answer. Both triumph and tragedy deserve a permanent place in the public sphere. Almost anything is better than silence.