Constitutional Textualism and Congressional Debate Over the 14th Amendment

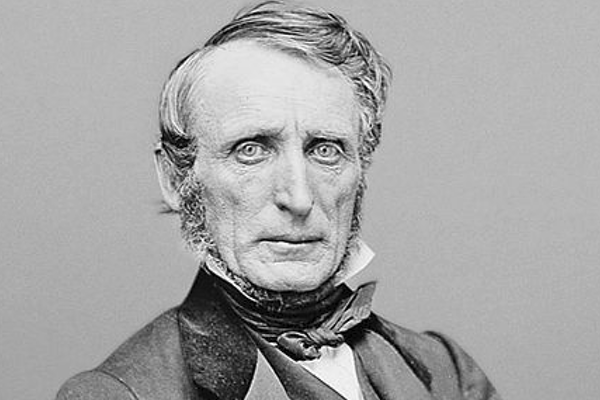

U.S. Rep. John Armor Bingham (R-OH)

Former Associate Supreme Court Justice Anton Scalia, the halcyon of judicial conservatism and the patron saint of the Supreme Court’s dominant bloc, justified his rightwing jurisprudence claiming to be a textualist. According to Scalia, “If you are a textualist, you don't care about the intent, and I don't care if the framers of the Constitution had some secret meaning in mind when they adopted its words. I take the words as they were promulgated to the people of the United States, and what is the fairly understood meaning of those words.”

Anton Scalia claimed we cannot know what the authors of the Constitution meant by what they wrote. But the thing is, their explanations of the meaning of the text are often well documented, especially as in the case of the 14th Amendment. Fortunately, while many current justices, like Scalia was when he served on the court, are limited in their understanding of what authors mean by the text, historian don’t have those limitations.

The Congressional Globe, predecessor to the Congressional Record, contains verbatim debate over the Fourteenth Amendment including extended statements by Congressman John A. Bingham from Ohio (House of Representatives, 39th Congress, 1st Session), the principal author of the amendment, and an elected official who could read very well, especially when the text was the United States Constitution. Bingham’s extended comments on the 14th Amendment appear on pages 1088-1094.

According to Bingham, “I propose, with the help of this Congress and of the American people, that thereafter there shall not be any disregard of this essential guarantee of your Constitution in any State of the Union. And how? By simply adding an amendment to the Constitution to operate on all States of this Union alike, giving to Congress the power to pass all laws necessary and proper to secure to all persons – which includes every citizen of every state – their equal personal rights . . .” Bingham clarified, “the divinest feature of your Constitution is the recognition of the absolute equality before the law of all persons, whether citizens or strangers….” Based on this, Bingham advised President Andrew Johnson that “the American system rests on the assertion of the equal right of EVERY MAN to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; to freedom of conscience, to the culture and exercise of all his faculties.”

As Bingham explained, “Equality before the law” under the Fourteenth Amendment means exactly what it says it means; it is a right guaranteed to “all persons, whether citizens or strangers.”

In his speech to Congress, Bingham echoed some of the arguments made by Frederick Douglass when Douglass rejected the idea that the United States Constitution was a pro-slavery document. Douglass denied “that the Constitution guarantees the right to hold property in man. Douglass believed “[t]he intentions of those who framed the Constitution, be they good or bad, for slavery or against slavery, are so respected so far, and so far only, as we find those intentions plainly stated in the Constitution . . . Its language is ‘we the people;’ not we the white people, not even we the citizens… but we the people…. The constitutionality of slavery can be made out only by disregarding the plain and common-sense reading of the Constitution itself.”

Bingham, who analyzed context, as well as text, stated that “everybody at all conversant with the history of the country knows that in the Congress of 1778, upon the adoption of the Articles of Confederation as an article of perpetual union between the States, a motion was made then and there to limit citizenship by the insertion in one of the articles of the word ‘white,’ so that it should read, ‘All white freemen of every State, excluding paupers, vagabonds, and so forth, shall be citizens of the United States.’ There was a vote taken upon it, for all our instruction, I suppose, and four fifths of all the people represented in that Congress rejected with scorn the proposition and excluded it from that fundamental law; and from that day to this it has found no place in the Constitution and laws of the United States, and colored men as well as white men have been and are citizens of the United States.”

Bingham turned the Comity Clause in the Constitution, which affirms that states must respect each other’s laws and was used by slaveholders to demand the return of freedom-seekers as stolen property, on its head. He argued it should be read as written; that “The citizens of each State shall be entitled to all the privileges and immunities of citizens in the several States.” He argues “This guarantee of your Constitution applies to every citizen of every State of the Union; there is not a guarantee more sacred, and none more vital in that instrument.” Essentially, Bingham believed, as did Douglass, that the slave states and slavery had been in violation of the Constitution all along, and the 14th Amendment, was need because its fifth clause empowered Congress to “enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article,” hopefully eviscerating the ability of states and localities to defy the law.

Supreme Court decisions based on text without context have been responsible for some of the greatest perversions of justice in United States history. The 14th Amendment empowered Congress to pass laws ensuring the rights of citizens and persons. One of the first laws, the Civil Rights Act of 1866, predated approval of the amendment, so Congress ratified it again in 1870. In Congressional debate over the law, Representative James Wilson (Republican-Iowa) explained that it “provides for the equality of citizens of the United States in the enjoyment of ‘civil rights and immunities,’ and that the civil rights protected by the law are “those which have no relation to the establishment, support, or management of government” (Congressional Globe, House of Representatives, 39th Congress, 1st Session, 1115-1117).

Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act declared “That all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theatres, and other places of public amusement.” Again, a right granted to persons irrespective of citizenship. Section 2 described penalties for violating the law.

But in 1883, by a seven-to-one vote, the Supreme Court endorsed Jim Crow racism as the law of the land when it ruled the Civil Rights Act unconstitutional. Writing for the court majority, Associate Justice Joseph Bradley argued that the Thirteen Amendment, as written, outlawed slavery, not discrimination, and the text of the Fourteen Amendment only authorized Congress to prohibit government action, not actions by individuals or non-governmental groups.

The only dissenting voice on the Court was Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan who wrote “The opinion in these cases proceeds, it seems to me, upon grounds entirely too narrow and artificial. I cannot resist the conclusion that the substance and spirit of the recent amendments of the Constitution have been sacrificed by a subtle and ingenious verbal criticism.” Harlan attacked the decision because “the court has departed from the familiar rule requiring, in the interpretation of constitutional provisions, that full effect be given to the intent with which they were adopted” and has “always given a broad and liberal construction to the Constitution, so as to enable Congress, by legislation, to enforce rights secured by that instrument.”

Harlan then cited an interesting precedent for his view of the Constitution – the Court’s position on Fugitive Slave Acts. According to Harlan, “Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793, establishing a mode for the recovery of fugitive slaves and prescribing a penalty against any person who should knowingly and willingly obstruct or hinder the master, his agent, or attorney in seizing, arresting, and recovering the fugitive, or who should rescue the fugitive from him, or who should harbor or conceal the slave after notice that he was a fugitive,” a view upheld by the Supreme Court in its 1842 Prigg v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania decision, which recognized the power of Congress to pass legislation enforcing the rights of slaveholders.

In a series of rhetorical questions about the Thirteenth Amendment, Harlan asked whether “the freedom thus established involve nothing more than exemption from actual slavery? Was nothing more intended than to forbid one man from owning another as property? Was it the purpose of the nation simply to destroy the institution, and then remit the race, theretofore held in bondage, to the several States for such protection, in their civil rights, necessarily growing out of freedom, as those States, in their discretion, might choose to provide? Were the States against whose protest the institution was destroyed to be left free, so far as national interference was concerned, to make or allow discriminations against that race, as such, in the enjoyment of those fundamental rights which, by universal concession, inhere in a state of freedom?”

Harlan warned, “Today it is the colored race which is denied, by corporations and individuals wielding public authority, rights fundamental in their freedom and citizenship. At some future time, it may be that some other race will fall under the ban of race discrimination. If the constitutional amendments be enforced according to the intent with which, as I conceive, they were adopted, there cannot be, in this republic, any class of human beings in practical subjection to another class . . .”

It is significant that in 1896, Harlan was the only dissenting voice in the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson legalizing the “separate but equal” doctrine that remained in effect until it was overturned in 1954 by the Brown v. Board of Education decision.

Returning to John Bingham and Congressional debate over the 14th Amendment, Bingham’s explanation of the amendment as an all embracing guarantee of civil rights was adopted by the woman’s suffrage movement, whose white leadership initially opposed the 14th Amendment because in its second section it included the word male, writing gender distinctions into the Constitution for the first time, and the 15th Amendment because it granted voting rights to Black men, but not white women.

In 1869, Attorney Francis Minor, whose wife Virginia was the President of the Woman Suffrage Association in Missouri, drafted a series of resolutions that were adopted by National Woman Suffrage Association and endorsed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Minor argued that the Fourteen Amendment barred “provisions of the several state constitutions that exclude women from the franchise on account of sex” as “violative alike of the spirit and letter of the federal Constitution.” Following up on these resolutions, in November 1872, Virginia Minor attempted, unsuccessfully, to vote in St. Louis, while Anthony and fourteen other women in Rochester, New York voted in the Presidential election and Anthony was later arrested. Francis Minor sued the St. Louis registrar because Virginia Minor, as a married woman, was legally not permitted to sue in her own right. In the case Minor v. Happersett (1875), the Supreme Court ruled that while women were citizens of the United States and the state in which they reside, the right to vote was a privilege not granted by the 14th amendment. John Marshall Harlan had not yet been appointed to the Supreme Court

In 1884, Susan B. Anthony testified before the Senate Select Committee on Woman Suffrage, “The Constitution of the United States as it is protects me. If I could get a practical application of the Constitution it would protect me and all women in the enjoyment of perfect equality of rights everywhere under the shadow of the American flag.”

Anthony’s testimony is of great importance today because the Supreme Court will be deciding a series of cases on the legal rights of both women and undocumented immigrants. Virginia recently became the thirty-eighth state to approve the Equal Rights Amendment, first passed by Congress in 1972. The amendment simply states, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” The version passed by Congress included an expiration date, later extended to 1982. Congress and the Supreme Court most decide if the expiration date is Constitutional and if the United States now has a new 28th Amendment.

The recent Supreme Court decision on DACA was narrowly decided on technical grounds and the Trump Administration is pursuing new legal avenues to end legal protection for about 800,000 undocumented immigrants who arrived in the United States as children. If the Court ultimately overturns DACA and subjects DACA recipients to deportation, at issue will be their Constitutional right to due process under provisions of the 14th Amendment.

Truth and democracy are also not mentioned in the United States Constitution. I worry these fundamental principles are endangered in the 2020 Presidential election if Donald Trump declares an electoral defeat to be “Fake News” and complicitous Republicans in Congress and a rightwing Supreme Court toss the election results because they can’t find the words in the text.