The Pentagon is Missing the Big Picture on "Stars and Stripes"

Editorial Room of Stars and Stripes, WWI

In February, the Pentagon proposed slashing funding for the famed soldiers’ newspaper Stars and Stripes, a story that roared back into the news in September after its publisher reported he had been ordered to halt publication by the end of the month. By the morning of September 4th, President Trump tweeted out his insistence that the paper would not be closing, though the Senate has not yet voted on a defense appropriations bill to resolve this issue. While veterans have raised important concerns about the elimination of an important journalistic voice independent of military officials’ control, administrators framed the paper’s closure as a budgetary issue to save $15.5 million - a seeming pittance in a department collecting over $705 billion in federal funding. If budgetary issues are truly the concern, I’d propose considering the paper’s history, which demonstrates how the paper actually can and does function as an important part of the public-private partnerships driving the country’s economy in connection with its journalistic mission.

In recent days, many articles have mentioned the paper’s roots during the Civil War, but few have described crucial developments during the First World War, when Guy T. Viskniskki, a Spanish-American War veteran and New York area journalist for the Wheeler Syndicate, argued a new paper describing the wartime experience through the eyes of rank-and-file servicemen could raise morale without becoming a form of propaganda. While training at Camp Lee outside of Richmond, Viskniskki established a newspaper for the community, one of many camp newspapers funded by the YMCA’s War Work Council. However, when he reached Europe in November 1917, Viskniskki dreamed of establishing a paper free from the oversight of his commanding officers and believed his knowledge of censorship regulations allowed him to effectively follow the rules placed on war correspondents. While Viskniskki was proud to highlight his paper’s financial successes and independence, the Intelligence Section provided the first 25,000 francs he needed to begin publication in January 1918. Viskniskki worked hard to push the paper beyond the narrow, divisional or company focus of other soldiers’ papers, rejecting calls to spin-off specialty publications for the Services of Supply because he believed a mass paper created a sense of unity spanning front and rear lines. He found his mass audience by providing troops with news of the war, tales from the home front including sports coverage, and comics, all written in a relatable, informal style. At its peak circulation near the armistice in November 1918, staffers printed 526,000 copies per issue and distributed them to readers on both sides of the Atlantic. When the paper closed shop in June 1919, the paper had even turned a profit (though Viskniskki was disappointed it was turned over to the US Treasury rather than distributed to French war orphans).

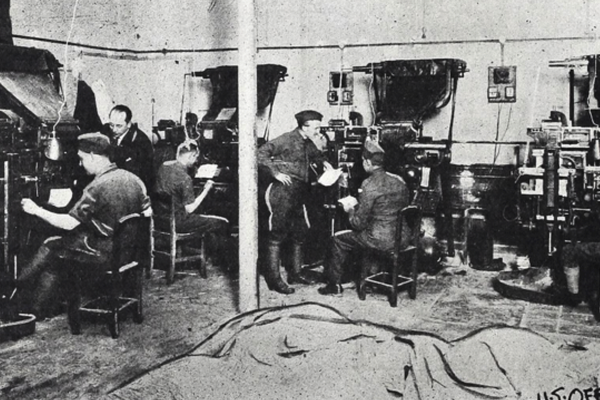

Stars and Stripes staff adjust linotype machines, WWI

Viskniskki financed his paper primarily through advertisements, securing free assistance from A.W. Erickson in New York. The paper charged perspective buyers the very low rate of one dollar per inch, raising it to six dollars when the cost of newsprint grew more cumbersome after circulation rose over 400,000. By the third issue, Viskniskki packed the paper with ads for products including Boston Garters, Colgate dental cream, Lowney’s chocolates, Wrigley’s chewing gum, 3-In-One oil, Mennen shaving cream, Fatima cigarettes, and Auto Strop razors. These advertisements were part of a broader modernization of military culture that introduced servicemen to new consumer products. For example, military regulations required troops to maintain clean-shaven faces to create a firm seal for their gas masks, thus requiring them to carry their own shaving kits and creating a market for the supplies advertised in their paper; a 1919 survey by the J. Walter Thompson advertising firm found that 30 percent of safety razor users learned of the product in the army. Similarly, army officers estimated that 50 percent of conscripts had not brushed their teeth on a regular basis, leading them to order over 4 million toothbrushes for troops who purchased toothpaste at local canteens or post exchanges.

Staffers for The Stars and Stripes also developed tools to effectively distribute their paper amid harsh wartime conditions. The paper secured subscribers by collecting a large cash payment up front, making it easy for delivery agents to simply drop off the paper rather than manage individual subscribers’ accounts. Viskniskki relied on staffers from Hachette, a leading French publishing house, to carry papers from train stations to troops even when they were under fire. The paper’s staff also acquired ninety-one cars that allowed field agents to deliver the paper to most remote regions where their readers served. Such decisions to develop an internal distribution service predated similar efforts by leading retailers by several years, as major mail order retailer Sears only developed their own trucking service in the early 1920s. The Stars and Stripes’ distribution network was so effective they approached the Red Cross and YMCA to assist them with their pre-USO era responsibilities of delivering treats and entertainments to troops across service areas.

Viskniskki was far from the paper’s only reporter, and its large and successful staff both reinforced the paper’s reputation for independence and established contacts that would further its commercial impact long after the war. While Viskniskki conducted the reporting for the first few issues primarily by swiping official cables from the censorship office, he quickly expanded his team by identifying experienced journalists who had difficulty fitting in with their units because of their writing habits. These included Harold Ross, whose commanding officer in a railway engineering unit forwarded Viskniskki many articles Ross had drafted alongside a plea to remove the man he considered the unit’s headache; New York Times writer Alexander Woollcott, who Viskniskki knew wanted to cover the front lines; New York Tribune sports reporter Grantland Rice who transferred from artillery work mere issues before Viskniskki decided to cancel the sports page amid Americans’ increasing combat responsibilities; fellow Tribune scribe Franklin P. Adams who opined on military life in his “The Listening Post” column; and Philip Von Blon, the enterprising reporter who developed sources within the SOS and broke the Harts uniform story. These writers formed a close social circle during the war and after, particularly after Ross founded The New Yorker and recruited Woollcott as a writer, palling around with Adams in their famed Algonquin Round Table meetings, while Von Blon returned home and took a job as managing editor of American Legion Monthly. Viskniskki himself declined to capitalize on the Stars and Stripes brand he created, turning down a $300,000 offer to establish a paper in the United States. However, other staffers risked Viskniskki’s ire and marketed their connections to the paper when founding veterans’ publications such as The Home Sector.

While short-lived, the World War One-era Stars and Stripes demonstrated the features that would become hallmarks of the paper when it resumed publication in 1942. The paper’s editors relied on funding from the government and its affiliates to open its doors, and it contributed to the country’s commercial development by inspiring new distribution ideas and familiarizing troops with new products for future consumption. Such factors clearly demonstrate why Congressional leaders are right to offer continued support for a paper that has shaped the country’s economy and culture for over a century.