The Queen's Two Bodies

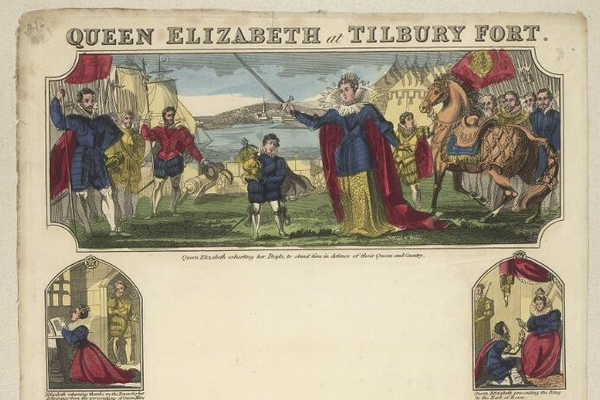

When on August 9th, 1588 Queen Elizabeth I appeared on horseback to inspect her troops at the seaside town of Tilbury, the soldiers having had amassed in preparation for a potential Spanish invasion, she was supposedly resplendent in gleaming armor, with a martial helmet framing her blazing red hair. The Spanish Armada was famously halted by the so-called “Protestant Wind,” the storms which spared the English both inquisition and occupation, and if there was an element of that respite which is central to its mythology, it’s Elizabeth’s appearance at Tilbury. “I am come amongst you… at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live and die amongst you all,” the Queen said during her famed speech to the troops, “to lay down for my God, and for my kingdom, and my people.”

Descriptions of the speech present Elizabeth as a stoic, regal, and dignified warrioress, with historian Garret Mattingly recounting in The Armada that the queen was “clad in all white velvet with a silver cuirass embossed with a mythological design, and bore in her right hand a silver truncheon chased in gold.” Elizabeth has been remembered, in contemporary epics such as Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene and recent movies like Shekhar Kupar’s Elizabeth: The Golden Age, as a war maiden, a virago, an Amazon. She has been remembered, at her own urging, as effectively a man.

“I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman,” Elizabeth said to her soldiers, “but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.” Writing in the academic journal PMLA, Mary Beth Rose says that Elizabeth is often seen as having functioned “politically by disarmingly acknowledging her femininity and then erasing it through appropriating the prestige of male kingship.” The speech at Tilbury is rightly considered an exemplary demonstration of Renaissance rhetoric, the strategically and politically brilliant monarch rallying a nation that faced an implacable foe, a ruler whose own position was precarious, but who combined both classical learning and the plain style into a patriotic argument concerning her own sovereignty.

Her call to arms does something else as well though, something which defined her reign – it gendered the Queen in a specifically masculine way, while making admission to the reality of her being a biological woman. Elizabeth’s speech thus has some fascinating resonances for us today, seeming to anticipate a more scientific understanding as summarized in the American Psychologist that “individuals show variability across the different components of gender/sex, presenting a mosaic of biological and psychological characteristics that may not all align in a single category of the gender binary.” It’s widely understood today that sex and gender are two different things, and that the latter need not match the former – something that Elizabeth gestured toward at Tilbury in 1588. What Elizabeth’s speech does is help to give us a more nuanced understanding of “gender” over the centuries, and the ways in which a more scientific accuracy was anticipated by her rhetoric.

So often the supposed strict gender binary between male and female, which is enshrined by traditionalists who are adamant on its universality, fails to take account of the ways in which our understanding of what it means to be a woman or a man has been different in the past, and often for surprising reasons. It should be made clear that the argument is neither that Elizabeth considered herself to be a man, nor that it would be appropriate to classify the Queen as being transgendered.

Yet as scholar Janel Mueller explained in a lecture delivered before the Washington DC chapter of the University of Chicago Alumni Club, Elizabeth had “no anxiety in representing herself as being above and beyond the social and biological mandates that her age attached to womanhood.” What Elizabeth’s speech does is provide an example of the difference between sex and gender from a surprising source, an illustration of the fact that gender is more complicated and variable than is sometimes assumed, and that during a time as authoritarian and reactionary as the Renaissance there could exist a progressive understanding of sexuality, albeit for ends which would seem foreign to us today.

Because if we can think of the Tilbury speech as “progressive,” insomuch as that’s a useful term, it was in spite of a profoundly regressive social context. When Elizabeth ascended to the throne, it was after the death of her sister Mary I, who, alongside her husband the Spanish King Philip II, ruled as the first female monarch given the traditional authority of a king. With the exception of her cousin Mary, Queen of Scots, Elizabeth was the sole European queen to be vested with the same awesome monarchical power as the absolute rulers of the continent, and the fact of her female body complicated her power during an otherwise profoundly misogynistic century.

Traditionally and mythically Elizabeth has been regarded as cagey tactician regarding her own cult of femininity; the emphasis on the Queen’s chastity and propagandistic representations of her meant to conjure an image of the Virgin Mary, whose icons had so recently been deposed in the English Reformation, all attest to the ways in which womanhood was used for political purposes. But as Rose writes, Elizabeth’s “rhetorical technique involves appeasing widespread fears about female rule by adhering to conventions that assert the inferiority of the female gender only to supersede those conventions.” Elizabeth’s words at Tilbury indicate that relying on tropes of femininity and virginity wasn’t the only way she solidified support, nor necessarily the most effective. What was even more authoritative, was that Elizabeth was able to imagine herself, and more importantly to compel her audience to imagine her, as being a man even while her biological sex was female. The authors of the American Psychologist article summarize the orthodoxy of the gender binary system which “typically assumes that one’s category membership is biologically determined, apparent at birth, stable over time, salient and meaningful to the self, and a powerful predictor of a host of psychological variables,” but Elizabeth’s declaration that “I have the heart and stomach of a king” greatly complicates that conservative perspective.

For both theorists and activists, clinicians and physicians, there has been a developing understanding that the gender which someone knows themselves to be may not culturally match the biological sex which others understand them to have. Research on the relationship between sex and gender has enriched our understanding of the blurriness of those terms, and the complexity between them. Interestingly, however, was that the more modern, complex, scientific, and accurate understanding was anticipated during the sixteenth-century and earlier. Historian Ernst Kantorowicz supplied a vocabulary for comprehending Elizabeth’s language in his seminal 1957 study The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology. In that work, Kantorowicz explains how for medieval and Renaissance political theorists, a monarch had to be understood as composed of two elements – the “body natural” which referred to their actual anatomical being, and the “body politic” which was the abstracted, spiritual, transcendent quality which marked them as sovereign. He writes that the “King’s Two Bodies thus form one unit indivisible, each being fully contained in the other.” For male monarchs, it necessarily holds that the masculinity of both the body politic and the body natural are in alignment; what makes the Tilbury speech so radical is that Elizabeth has allowed for the possibility of a female body being unified with the male body politic, she has in essence spoken in a language which anticipates the subtlety, nuance, and complexity of gender which we’ve come to more fully understand in the past century.

The King’s Two Bodies was a political-theology designed and understood to uphold a reactionary system, and yet by serendipity it could also inadvertently allow for more enlightened conclusions, as when Elizabeth challenged not just the Spanish Armada at Tilbury, but the strictures of a constructed gender binary as well.