Recovering Acts of Progressive Patriotism: Teaching Through Protest Music

Anna Klobuchar Clemenc and the Italian Hall of Calumet, MI

The concept of patriotism has received a great deal of attention during the Trump administration, with the president and his supporters doubling down on the celebratory and mythic varieties. Lacking any formal ties to military service, the president is left with what scholar Ben Railton refers to as exclusionary mythologizing, which is not patriotism at all, but rather blind nationalism (read Ben Railton’s essay on patriotism for HNN—ed). At the top level, it involves bullying and bombast. On the ground, it includes hawking of merchandise, owners adorning their trucks with both American and Trump flags, highway overpasses commandeered by fanatic supporters flying similar flags, and a whole lot of divisiveness.

Regardless of the outcome of the election, such branding will no doubt be appealing to certain politicians and segments of the population. Yet, Railton sees an opportunity to highlight other types of patriotism in America’s past, including participatory and critical patriotism, underscoring the importance of recovering stories and histories that are often overshadowed or forgotten. While teaching a recent course using music history titled “Roots, Rock, Rebels”, my students and I had the opportunity to explore two such cases of critical patriotism that drew specific connections to and use of the American flag. In both cases, however, hope gave way to backlash or defeat, at which point musicians offered another yet another type of protest.

The course came together through a mix of inspirations, starting with the first piece of the puzzle, when our department hosted authors Doug Bradley and Craig Werner during their lecture tour in promotion of the book We Gotta Get Out of This Place: The Soundtrack of the Vietnam War. Their presentation included conversations with multiple veterans in the audience and did not shy away from the theme of critical patriotism. They played numerous samples of music, with Werner suggesting that a favorite class activity was listening to Marvin Gaye’s What’s Goin On album from start to finish. Werner is also the author of A Change is Gonna Come: Music, Race, and the Soul of America, a book not only suitable for the class, but also containing multiple examples of participatory and critical patriotism.

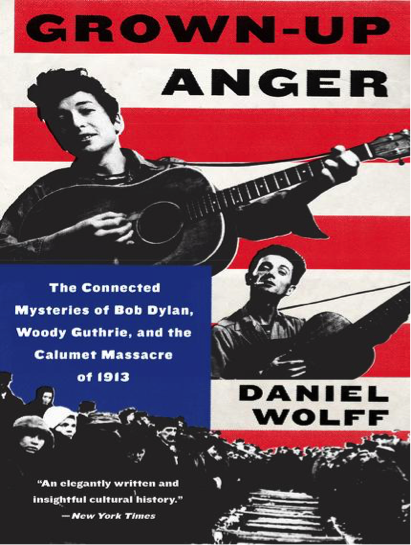

As these ideas were coalescing, a final piece to the puzzle came together with the publication of Daniel Wolf’s Grown Up Anger: The Connected Mysteries of Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, and the Calumet Massacre of 1913. Wolf’s study of a tense labor dispute and the tragedy that followed became the core research focus of our course. Numerous primary sources guided our study, along with Steve Lehto’s comprehensive book Death’s Door: The Truth Behind Michigan’s Largest Mass Murder. Publicly, Lehto was critical of Wolf’s scholarship, but this misses the significance of Wolf’s book as Wolf shows a pattern in which a struggle occurs, but those holding power win out and attempt to extinguish the hope of those seeking progressive changes, sweeping them to the dustbin of history and their place in America’s identity in the process.

Musicians, however, stood as historical witnesses to forgotten or frustrated histories and were, according to Wolf, willing to “tell the truth” through anger. Channeling anger instead of folkish hope, Woody Guthrie looked back on the Calumet massacre in writing the topical ballad 1913 Massacre in 1941. Bob Dylan later performed the song while also using the same melody in writing Song to Woody. It was his classic Like a Rolling Stone, however that Wolf references as the ultimate truth telling song, full of anger and not hope. Using the historical skill of sourcing that historians employ, one realizes the song was released in 1965, two years after the progressive hope of the March on Washington often associated with Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic speech.

Although Wolf does not make a big deal of it, my students and I zeroed in on two very noticeable uses of the American flag as we reviewed the interconnected histories of Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and Mahalia Jackson, and also the similar theme of hope and critical patriotism displayed by immigrant laborers and later African Americans across the first seven decades of the twentieth century.

The first came in our study of the Calumet massacre that angered Guthrie many years later, so called because after an intense standoff between laboring miners and the Calumet & Hecla Mine Company, seventy-three individuals, most of them children, lost their lives in a crushing stampede in the stairwell of the town’s Italian Hall after someone opened the door and yelled fire. After the false alarm was sounded, the door was barred shut, with many believing mine ownership and their police force were behind the tragedy, adding insult to injury. Throughout the build up and aftermath of the tragedy, however, labor leader Annie Clemenc stood tall. In fact, she was often referred to as “Big Annie.” She was also not afraid to use the American flag to support the cause of first-and second-generation laborers seeking better wages and working conditions.

Annie Klobuchar was born in 1888 to Slovenian parents living in Calumet, Michigan, a town in norther Michigan’s iron range that drew many first-and second-generation immigrants to work the rich copper vein. In 1913, tensions boiled over between the Calumet & Hecla Mining Company and their laborers. By mid-summer, the laborers were on strike. This did not stop the owners from hiring replacement workers and security forces to harass the striking laborers. In the midst of the turmoil, Annie starting leading daily marches on behalf of the striking workers, putting the full force of their progressive demands for better wages and working conditions behind a ten-foot American flag, which she carried daily on her marches. Over time, she was joined by defense attorney Clarence Darrow, John Mitchell, President of the United Mine Workers of America, and labor activist Mother Jones. Leadership of the movement were proud to call themselves socialists, or at the very least read from socialist newspapers. They were also proud to use the ideals of the American flag to support their progressive hopes as they aimed constructive criticism at mine ownership who held the balance of power.

Using replacement labor, force, and even time, ownership won out as 1913 wound down and winter approached. Looking to add a bit of cheer in their lives, labor leadership hosted a Christmas party for many of the children in the area. The pursuant disaster further broke their spirit, yet Annie did not abandon the flag. On December 28, 1913, Clemenc led a parade of mourners, once again carrying her ten-foot flag at the head of the procession. This time it was draped in black crepe, and later positioned prominently at the cemetery as eulogies were read in Finnish, German, Italian, English, and Croatian for many individuals soon forgotten in the American story. That is, until Woody Guthrie’s anger sought to “tell the truth,” while Guthrie himself was working out definitions of Americanism amidst the backdrop of World War II.

The second prominent example in which we found the American flag as a part of a progressive cause came later in the course when studying singer Mahalia Jackson in Werner’s book A Change is Gonna Come. Jackson was a musical icon who brought gospel from the church to mass audiences. After meeting King in 1956, she agreed to sing at a fundraising rally in support of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Thereafter, she remained loyal to King, lending not only her talents to his speaking engagements, but also motivation. She was at the March on Washington (note the image of Jackson framed by two American flags as she made her way to the stage). Performing on stage, images of Jackson are framed by American flags. Playing the audio of the performance while projecting an image of Jackson in front of a flag was a poignant reminder that those marching and taking to the stage identified with the ideals of the flag and dared to dream of inclusion in America’s story—past, present, and future.

The art of historical detection also indicated Mahalia Jackson played a critical role in encouraging King’s “I Have a Dream Speech.” King took to the stage with a pair of metaphors in mind. At a point when his prepared speech, which did not include the lines about the dream, hit a bit of a snag, Jackson leaned in, as she did many times before, and offered the words, “Tell Them About the Dream Martin, Tell Them About the Dream.” Flags fluttering in the backdrop were met with the words of hope as King, Jackson, and others standing at the base of the Lincoln Memorial participated in a protest of critical patriotism that dreamed of hope for an inclusive America. A few short years later, the Civil Rights Bill followed. Despite the hope and the subsequent policy change, racism and profiling persisted. So did violence as the 1960s stretched to a chaotic end over the second half, thus betraying the hope of the first.

Historical detection also tells us Bob Dylan participated in the March on Washington, as protestor and performer, taking the stage, albeit somewhat awkwardly, to sing Only A Pawn in Their Game. Already aware of historical injustices invoked by his hero Woody Guthrie, Dylan added to the catalog of injustices, increasingly willing to get at the truth through anger. In 1964, the same year as the Civil Rights Act, he recorded The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, chronicling 1960s racism on his album The Times Are a-Changin. One year later, he released Like a Rolling Stone on his Highway 61 Revisted album. Wolf argues this song found Dylan at his most angry, as if outrage was the only way to respond to the world. Over the following years, Dylan’s music changed, even prompting critic Greil Marcus to muse “What is This Shit?” in a Rolling Stone review.

In the mid-1970s, a rejuvenated Dylan resurfaced in time to celebrate America’s birthday by organizing the Rolling Thunder Review. It is no coincidence that the first stop on the tour was at Plymouth, Massachusetts, a location where rebels once settled, but also a location that assumes meaning in the malleable mythmaking of America. One of the more electric songs on the set was Dylan’s recent release, Hurricane, a protest song, telling the story of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, a tale of racial profiling and injustice that would sadly fit with 2020 America.

The Rolling Thunder Review also included a stop at the Tuscarora Reservation in New York, where Dylan led a rousing cover of Peter La Farge’s The Ballad of Ira Hayes, proving more truth needed to be told. Hayes’ post World War II story ended tragically following his act of participatory patriotism at Iwo Jima, first in service of his country as a Pima Native American, but most iconic as one of a handful of Marines raising the flag over the island in victory. The latter is part of the American myth, while the former, including Hayes’ overall story, and even the service of Native Americans to America, is often forgotten. Tellingly, the Rolling Thunder Review ended each night with a rollicking rendition of Woody Guthrie’s This Land is Your Land, a song many view as an inclusive alternative to the national anthem.

The connections explored here unearth histories of critical patriotism through progressive protest. Throughout, the flag is used as the ideals of fairness, liberty, and justice are applied to its meaning. As such, these are protests not against the flag, or America, but rather injustices, with the hope of finding a better, more equitable and inclusive America. When these hopes are swept under the rug and struggles are ignored and discarded into the dustbins of history, the injustices can reach a point of simply being too overwhelming. Woody Guthrie’s 1913 Massacre and Bob Dylan’s Like a Rolling Stone(along with his mid-1970s material) are songs of anger and truth telling, with the musicians using what was familiar to them.

Contextualizing events from the historical past in which hopes and dreams that rallied behind the flag were crushed, ignored, or met with backlash are critical in framing current discussions and broadening definitions of patriotism. For Guthrie and Dylan, it was using music to express disappointment and even anger after hope was ignored. Might we consider Colin Kapernick’s act of kneeling during the anthem, along with fellow athletes who have use their platform of fame in following, in a similar vein? Theirs is not a protest against a flag, but rather injustices that exclude from all the positive and progressive meanings the flag could represent.