Leaders Have Shirked Responsibility When Pandemics Affected Presidents

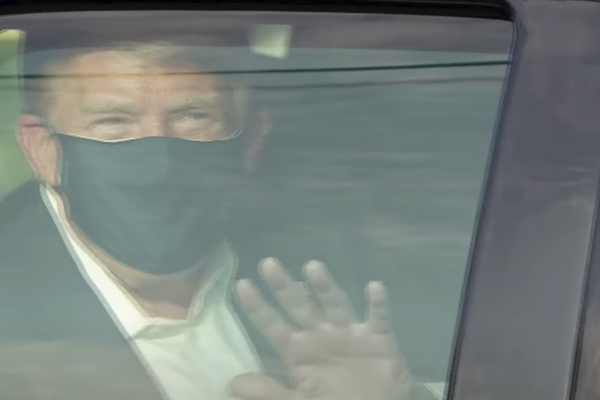

President Donald Trump appeared emotionally volatile throughout his presidency, but his behavior turned more erratic after he came down with COVID-19 and received emergency treatment at Walter Reed hospital. Could neurological disorders explain Trump’s controversial actions following his sickness in October?

New medical research shows COVID-19 can affect the brain. If coronavirus influenced Trump’s behavior, this is not the first time a pandemic may have affected presidential decision-making. Woodrow Wilson contracted the “Spanish Flu” in 1919, and sickness complicated his work at the post-World War I peace conference. The behavior of Wilson and Trump suggest leaders in Washington ought to be more responsive when questions arise about a president’s capacity to lead.

There is growing evidence that the coronavirus can alter thought and behavior. “The neurological symptoms are only becoming more and more scary,” reported Alysson Muotri, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego. A team of researchers at New York University conjectured that the virus leads to neurological injuries in one out of every seven infected people. Trump’s thought and actions may have been further influenced by treatments he received at the hospital. Doctors gave the President a steroid, dexamethasone, which can produce mood changes such as aggression, agitation, anxiety, irritability, mental depression, and difficulty thinking and speaking.

Pandemic-related complications appear to have affected an earlier president’s decision-making. Woodrow Wilson fell seriously ill during the great influenza of 1918-1919. A dramatic change in mood and behavior occurred at the time, as John Barry recounted in his 2005 book The Great Influenza. Herbert Hoover, who attended the meetings in Paris, noted that Wilson had been “incisive and quick to grab essentials” prior to his illness and was “willing to take advice.” Then, said Hoover, “I found we had to push against an unwilling mind.” The Chief Usher, Irwin Hoover, observed “something queer was happening in [Wilson’s] mind. Once thing was certain: he was never the same after this little spell of sickness.”

Before President Wilson’s experience with the flu, he advocated a fair and just peace settlement with Germany and the Central Powers. At the time of the illness, however, Wilson suddenly capitulated. He yielded to the French, British and others that demanded the Germans pay huge reparations, surrender control of land and industries, and sign a war guilt clause. John Maynard Keynes, who attended the conference, noticed that European negotiators took advantage of Wilson’s weakness. Keynes worried the harsh terms could excite resistance in Germany and lead to another war. Influenza may have made a much greater impact on global events than previously recognized.

Did a pandemic affect President Trump’s behavior? Trump acted strangely after his troubles with COVID-19 and medical treatment, but it is difficult to identify cause and effect. Trump’s mental state has been a subject of speculation throughout his presidency. His post-hospital behavior can be interpreted as a continuation of erratic conduct.

Nevertheless, considerable evidence suggests Trump’s sickness from COVID-19 and medical treatment may have led to a shift in behavior. The President’s actions after his episode with the coronavirus were extraordinary. Following release from the hospital, Trump demanded the Justice Department lock up Joe Biden, Barack Obama, and Hillary Clinton. He lambasted loyal allies, including Mitch McConnell, Mark Meadows, and William Barr. Trump refused to accept defeat and made unsubstantiated claims about fraudulent ballots. He alarmed aides by considering recommendations to declare martial law, seize voting machines, and appoint a conspiracy theorist as special prosecutor. And, on January 6, the President incited a mob to attack the US Capitol as a joint session of Congress worked to ratify the Electoral College vote and formalize his defeat.

In both Donald Trump’s and Woodrow Wilson’s cases party officials responded inadequately. Following Wilson’s troubles with influenza and a major stroke, Republicans warned that the president was unable to discharge his duties effectively. They were correct, but Democrats failed to act. For a year and a half, the United States operated under a shadow government. Two unelected individuals, Dr. Cary Grayson and Wilson’s wife, Edith, spoke for Wilson, claiming to identify his wishes. The nation lacked a capable president during those seventeen months. Since his episode with the coronavirus, President Donald Trump appeared unhinged, yet Republican officials refused to discuss the matter openly.

Political leaders can serve the public better if they recognize that sometimes deference to authority is risky. Presidents are human. When challenged by severe physical or mental problems, they may be in poor condition to make vital decisions about domestic and international affairs. In such extraordinary circumstances, it is patriotic to consider a transfer of authority briefly or permanently.