Kamala Harris and the Modern Vice Presidency

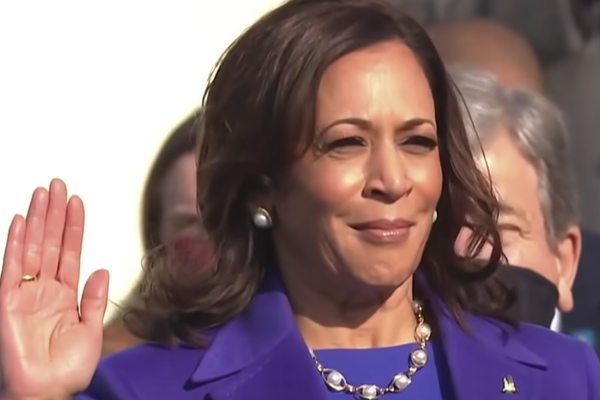

Now that Kamala Harris has become the first woman as well as the first person of color to be sworn in as vice president of the United States, she and President Biden are already tackling arguably the most formidable set of challenges to face the country since Abraham Lincoln confronted the prospect of civil war in 1861. Significantly, she is serving with almost surely the most consequential vice president in American history, Joe Biden, who will be transferring much of his successful experience to her, with the two of them building on the 40-year transformation of the office.

All this means, in short, that “the modern vice presidency” has achieved an optimal moment in its steady evolution because the president of the United States, Joe Biden, has enhanced the office he held under President Obama and is already hugely invested in Kamala Harris’s success; he will have his own ideas, as well as hers, and every incentive to further enhance her role.

The recently verified Georgia Senate election results mean that Harris’s duties will immediately include performing her only constitutionally-specified duty: presiding over the Senate and breaking tie votes, which are likely to be frequent in a body now divided 50-50.

An additional benefit to Harris in her other work is that the White House chief of staff, Ron Klain, has previously served as chief of staff to Vice President Biden and is thus familiar with how the new arrangement works and will likely have her back when difficulties arise. Moreover, Harris and Klain will inevitably become the two most Important players in the West Wing and, if history is any guide, they will be in and out of the other’s adjacent offices frequently seeking consensus on recommendations to the president and dealing with the crises of the day.

It’s a far cry from the 200 years during which the vice presidency was a position of neglect and ridicule. That changed in 1976 when Jimmy Carter decided to lift the office from its obscurity and make it instead an “asset” of the presidency itself and integral to the governing process. While interviewing potential VP candidates, he encountered Minnesota Senator Walter Mondale, who had witnessed his friend Hubert Humphrey, and later Nelson Rockefeller, suffering under presidents who gave them little to do as vice presidents and kept them removed from serious policy discussions. Mondale came to the meeting with Carter determined not to be similarly marginalized; he was only interested if he would have a “substantive” role.

Carter selected Mondale, and after a successful election, I sat down with the two of them at Blair House in December for the first discussion of Mondale’s role. Mondale proposed that his principal activity be as an across-the-board advisor to the president; to do that he needed unfettered access to the president and the information flow through his office, including national security discussions. After an hour’s discussion, Carter said he liked Mondale’s ideas and requested a memo detailing them. We quickly drafted and sent an 11-page memo to the president-elect, who approved it in its entirety two days later.

President Carter soon offered his own thoughts, all of them insightful and unprecedented. He gave Mondale an office in the West Wing; he told his cabinet and staff to regard a request from the vice president as if it came from him, the president; he added that he would not tolerate anyone trying to undercut his vice president. He made me, Mondale’s chief of staff, a member of his own senior staff. All of this sent a clear signal that the nation’s second highest office had been fundamentally changed or, as Carter later put it, “executivized.”

The Carter-Mondale model has been used, sometimes with variations, by nearly every subsequent administration to the point where it has become virtually “institutionalized through use” (no constitutional or legal change necessary). The keys to the success of the arrangement are candor and mutual trust. Carter and Mondale had a weekly lunch where just the two of them could speak frankly about anything on their minds. These confidential moments helped shape a unique partnership based on trust that worked well for four years.

Although the modern vice presidency has become a major asset to the president, it’s nonetheless an office of almost total dependency, and therefore still a fragile instrument wholly reliant on mutual respect which, happily, was already evident in Harris’s full inclusion in the Biden cabinet interviews and other key transition meetings and now in the new Administration’s first days.

The vice president’s most valuable asset, like the president’s, is time. One of the features of the modern vice presidency is that the chief executive can delegate tasks to his number two who can carry them out, in the view of others, with authority. This makes it essential that the two decide how Vice President Harris can best help President Biden pursue his first-year agenda, keeping in mind that she can be called to the Senate any time a tied vote seems possible.

Out of the gate, she needs to move quickly to where she can make the most difference. That was essentially the Mondale model, but other principals have decided that the vice president should head up major administration initiatives, such as Biden performed for Obama in implementing the Recovery Act and other priorities. Both models have merit and legitimacy; the answer in ordinary times lies in how the needs of the president can best be matched with the abilities and experiences of the vice president.

But these are not ordinary times, and there is only one other nationally elected official who can speak with authority for the president on the urgent issues of coronavirus, the economy, racial injustice, climate change and civil insurrection.

They should consider delaying for six months a hard decision on which model to follow, allowing Vice President Harris to spend time in or near the Senate, with the flexibility to go where President Biden believes she can be most effective in pursuing his agenda. That time will give them both a clearer perspective on how they can best work together, and which model -- or even a new one--is best suited to them and their agenda. The modern vice presidency can have its brightest moment yet, if Kamala Harris can take it to another new level for her successors to emulate, as Biden has before her.

Joe Biden surely agrees that a vice president’s serious engagement in White House decision-making is the best preparation anyone could have if called upon to be president. Our first vice president, John Adams, who had no such preparation, captured it perfectly, “I am nothing, but I may be everything,”

I once asked President Carter what had caused him to focus on enhancing the role of the vice president. He said unhesitatingly that it was when he learned that Vice President Harry Truman was unaware of the atomic bomb before he succeeded to the presidency. President Carter deserves great credit for having the historical insight to reconsider how we govern ourselves at the highest levels of our government; we should be grateful that he has lived to see this time when his idea has reached this moment of such acceptance and promise.