How Biden used the VP Springboard to Vault into the Oval Office

The vice presidency is America’s best presidential springboard. That’s why Vice President Kamala Harris and former Vice President Mike Pence are considered leading presidential contenders in 2024 or 2028, even after Pence’s recent falling out with President Donald Trump affected his standing. Yet, as a former vice president who has been elected president, Joe Biden is an anomaly. This paradox--that the vice presidency boosts presidential prospects but vice presidents are rarely elected president--suggests insights about the vice presidency and about Biden.

Presidential wannabes have sought to be vice president especially since Richard M. Nixon (1953-61) demonstrated its political spring. The office elevated Nixon from a backbench legislator to the 1960 Republican presidential nominee. Nixon narrowly lost that race but was elected president as a former VP (1968) and George H.W. Bush (1988) was elected while Ronald Reagan’s vice president. Every Democratic vice president since 1953 has become a presidential nominee—Hubert H. Humphrey (1968), Walter F. Mondale (1984), Al Gore (2000), and Biden (2020), not to mention Lyndon B. Johnson (1964) who was nominated after succeeding to the presidency upon John F. Kennedy’s death.

Although vice presidents get a head start in the presidential race, few before Biden crossed the finish line. Biden is the 15th vice president to serve as president, but nine of those became president initially when their predecessor died or resigned, not by election. Of the six who were first elected, four were sitting vice presidents—John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Martin Van Buren, and George H.W. Bush—but Adams and Jefferson were elected under the original system which was abandoned in 1804 in which the vice presidency was awarded to the electoral college presidential runner up, so their ultimate elevation was not so surprising.

For most of American history, the vice presidency was insignificant and its occupant didn’t even figure in presidential speculation. After Vice President John Breckinridge received 72 presidential electoral votes in 1860, no sitting or former vice president who had not become president by succession was nominated to seek the presidency by a major party.

Even when that changed in the mid-20th century, Vice Presidents Nixon (1960), Humphrey and Gore narrowly lost presidential bids. It was Mondale’s misfortune to run against Reagan who was lifted by a rising economy amidst “Morning in America.” Biden is only the second former vice president, after Nixon, who had not succeeded to the presidency, to be elected president.

Performing on a national and international stage allows vice presidents to increase their name recognition and presidential plausibility. Speaking at public and party events provides unique opportunities to expand contacts and develop relationships which may pay off in future presidential races. These advantages helped many recent vice presidents become presidential nominees after earlier unsuccessful attempts.

But the office also has a political downside. Vice presidents inherit administration baggage even if they’d have done things differently. Humphrey couldn’t escape Johnson’s Vietnam policies, Mondale was saddled with the legacy of 21% interest rates and Americans held hostage during the Carter years, and Gore was hurt by Bill Clinton’s “inappropriate behavior,” which obviously didn’t involve him. And vice presidents often have trouble presenting themselves as leaders after four or eight years in the presidential shadow. The public may not perceive the familiar number two as a number one and some vice presidents have trouble pivoting, too. Notwithstanding their political divorce during the last two weeks of their term after Pence refused to overstep his limited role presiding over the electoral count, Pence may find the “baggage and shadows” problems even more daunting than did his predecessors, given his obsequious praise of Trump for most of their term and his association with the Trump administration’s mishandled pandemic.

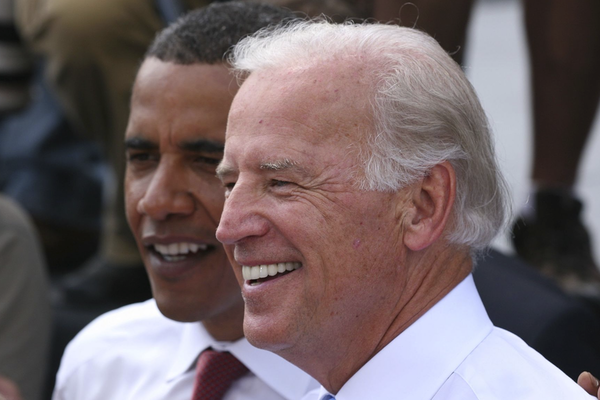

So how did Biden become a historical rarity, a former vice president elected president? Like his predecessors, the vice presidency made Biden a more plausible presidential candidate with an expanded rolodex. Working with an effective and popular president helped, too. Biden in 2020 wasn’t the same candidate who had presented himself in 1987 and 2008.

Yet Biden 2020 success didn’t happen just because he was Obama’s vice president, but because of how he handled that opportunity. Biden was a loyal vice president without surrendering his own integrity, dignity, or distinctive brand. His performance enhanced his credibility with insiders who admired his governing skill and with reachable voters who sensed his empathy and shared his values. Even against a large, diverse and talented Democratic field, that political capital enabled him to survive early setbacks unprecedented for a nominee until his South Carolina and Super Tuesday success made his nomination inevitable. Resilience is among Biden’s qualities as his road to nomination demonstrated again.

Biden’s vice presidency communicated his decency and authenticity, a perception that shielded him from the Trump campaign’s attacks. Critics had dismissed Biden as gaffe prone yet his disciplined vice presidency foreshadowed his well- ordered and well-executed general election campaign.

Circumstance helped, too. Biden contrasted perfectly with his contemporary Trump—decency vs. nastiness, empathy vs. narcissism, governing skill vs. incompetence, a broad vs. base-oriented pitch and appeal.

The vice presidency gave Biden a stage on which to showcase his skill and character but it also provided a governing education at the highest level. That experience gave this life-long learner an opportunity to hone his game. Biden 2020 was a better model than what came before, something demonstrated since election day as he and his talented team skillfully navigated an extraordinary transition and produced an inspiring inauguration and beginning.

The vice presidency boosted Biden, and working with Obama and running against Trump helped. But Biden is our 46th president in large part because of what he did and learned as our 47th vice president, not simply because he held that office. That’s a lesson for future vice presidents and others seeking to understand the nature and extent of the vice-presidential advantage.

copyright Joel K. Goldstein, 2020