What the Policing Response to the KKK in the 1960s Can Teach about Dismantling White Supremacist Groups Today

Archival image from 1967 shows protesters demonstrating while Ku Klux Klan members walk in a parade to support the Vietnam War. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

David Cunningham, Washington University in St Louis

During his confirmation hearing in February, Attorney General nominee Merrick Garland pledged that his first order of business would be to “supervise the prosecution of white supremacists and others who stormed the Capitol on January 6.”

On that day, thousands of Trump supporters – including members of white nationalist and militia groups – gathered to support and defend a series of fabricated and conspiracy-laden claims around the purportedly “rigged” 2020 election.

As a social scientist who researches how white supremacist groups are policed, I understand both the need to vigorously address threats of violence from racist and anti-democratic elements and the calls from some Justice Department officials to expand police powers to do so.

But if history is a guide, providing police with new tools to address current white nationalist threats could result in further repression of activists of color.

The campaign to police the civil rights-era Ku Klux Klan, for example, offers clear lessons in this respect. While that effort prevented white supremacists from capitalizing on their momentum in the mid-1960s, it also spurred unforeseen consequences.

KKK in 1965

Nearly every night in 1965, ascendant KKK leader Bob Jones appeared on a makeshift stage in fields across rural North Carolina channeling the revolutionary fervor of his newfound followers.

Bob Jones, right, a leader of the Klu Klux Klan in North Carolina, stands with Calvin Craig of Georgia during a KKK rally in Atlanta in 1967. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

As the head of the nation’s largest statewide Klan since World War II, Jones was growing accustomed to crowds numbering in the hundreds – and sometimes the thousands – at rallies throughout his home state.

The previous fall, President Lyndon Johnson had defeated archconservative Barry Goldwater. Jones’ KKK had strongly backed the loser, who had aligned himself with Southern segregationists. Now Jones drove a shiny new Cadillac purchased from KKK dues. His bumper sticker read: “I’m not ashamed, I voted for Goldwater.”

Though Jones did not contest the election’s legitimacy, Goldwater’s defeat caused the KKK leader’s crowds to swell in size and intensity. Supporters seemed newly energized in their aggrieved alienation from national politics. When LBJ spoke out against an increasingly deadly spate of Klan violence, Jones drew more than 6,000 to a rally celebrating known KKK perpetrators.

Jones clearly recognized that opposition from the White House energized his base. “If Lyndon Johnson makes three more speeches,” he proclaimed, “we could quit renting fields and start buying farms.”

Police crackdown

In March 1965, a bipartisan group of congressional lawmakers urged the House Committee on Un-American Activities to investigate the Klan. Formal hearings were announced that June.

The resulting scrutiny led police to challenge KKK rally permit requests and aggressively investigate cross burnings and other intimidation tactics they had previously dismissed as not hurting anyone.

At the same time, the FBI’s COINTELPRO program received more latitude to use informants and other counterintelligence techniques. As the bureau’s own memos specified, agents worked to “expose, disrupt and otherwise neutralize” domestic subversives like the KKK.

Such measures also created a safer space for concerned citizens to publicly oppose organized vigilantism. By 1969, in North Carolina and throughout the South, the KKK had all but ceased to operate as a mass membership organization.

But, crucially, such short-run success came with significant costs.

Unforeseen consequences

Aggressive moves to dismantle the Klan’s ability to organize pushed its militant core underground. There, it metastasized into lone-wolf or cell-based violence. As one former Klan member described it, racist resistance evolved into a “game of ones.” Left unchecked by any coordinated organization, white supremacists posed a threat that became even more volatile.

The crackdown also failed to rid areas of political and racial divisions that the KKK had stoked. Research I’ve conducted with sociologists Rory McVeigh and Justin Farrell shows that, even after accounting for a wide range of competing explanations, areas where the KKK was active in the 1960s continued to display – even 50 years later – significantly higher levels of violent crime and political polarization.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, police ultimately deployed their expanded powers not primarily against the KKK, but against activists in communities of color that have always borne the brunt of state control.

For example, FBI agents’ newly gained authority to infiltrate and disrupt the KKK quickly extended – with deadlier consequences – to members of the civil rights and Black nationalist movements.

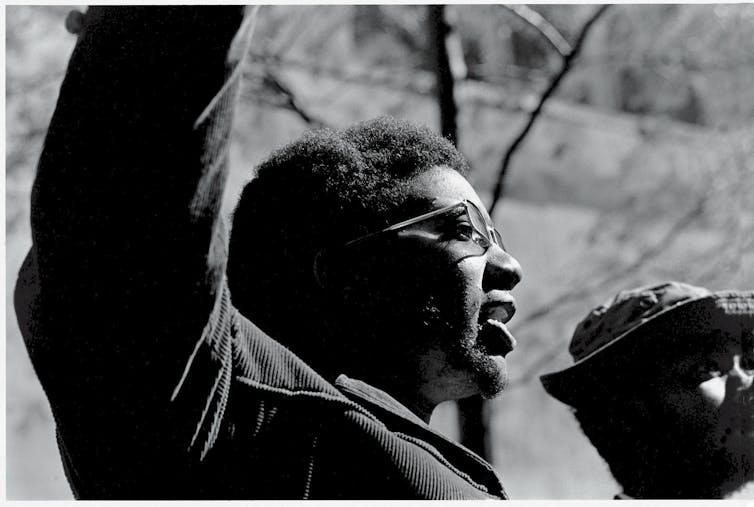

Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton raises his arm at a rally in Chicago in October 1969 – just two months before police raided his home and shot him to death. David Fenton/Archive Photos via Getty Images

Such efforts sought to destroy grassroots activist organizations and disrupt personal relationships between their members. And as the current film “Judas and the Black Messiah” powerfully depicts, they also led to campaigns to eliminate charismatic and effective movement leaders, including Illinois Black Panther Party Chairman Fred Hampton and Martin Luther King Jr.

Relevance today

Today, some Justice Department officials are pushing to label Trump-supporting insurrectionists as domestic terrorists. Such aims would bolster criminal legal strategies they hope will stem the tide of political violence.

At the same time, media reports have highlighted the differences in treatment between the seemingly permissive stance adopted toward the violent insurrectionists on Jan. 6 and the far more pronounced police crackdown against largely peaceful Black Lives Matter protests throughout the summer of 2020.

As President Joe Biden tweeted on Jan. 7, “No one can tell me that if it had been a group of Black Lives Matter protesters yesterday that they wouldn’t have been treated very differently than the mob that stormed the Capitol.”

Of course, there is a strong case for pressing police to use existing tools to arrest and prosecute those who engaged in violence and other crimes at the Capitol, as well as to heed officials’ calls to confront and defeat an emboldened white nationalist movement.

But doing so can risk expanding police powers in ways that history demonstrates may be turned on those who have been seeking justice all along.

[Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter.]

David Cunningham, Professor and Chair of Sociology, Washington University in St Louis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.