Recommitting America to Historical Principles of Obligation to Veterans

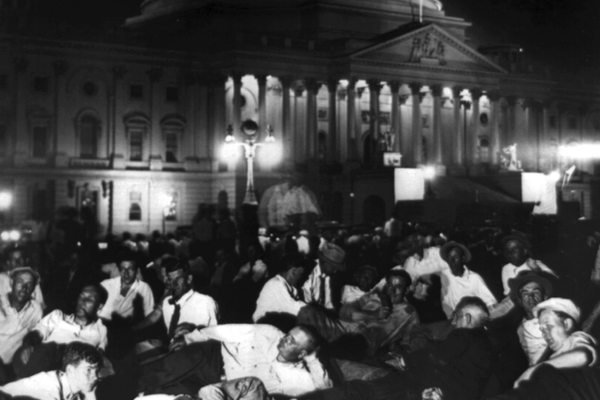

Bonus Marchers camp at US Capitol, July 13, 1932

Veterans’ law is a dead letter. Twenty years after 9/11 and almost 50 years after the beginning of the All-Volunteer Force, the veterans’ benefits system needs reform. At stake are recruitment and retention, the pillars of the United States’ All-Volunteer Force and the heart of the common defense. Because reform must begin with first principles, the United States must once and for all upend the faulty premise that veterans’ benefits are mere gratuities.

Less than a generation after President Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address—in which he expressed the imperative “to care for him who shall have borne the battle,” the source of VA’s motto—the U.S. Supreme Court, in 1883, announced: “Pensions are the bounties of the government, which Congress has the right to give, withhold, distribute, or recall, at its discretion.” Courts have since transmuted this passage into the proposition that all veterans’ benefits are mere gratuities. This proposition serves as the foundational premise for veterans’ benefits administration and adjudication. History reveals why it’s wrong.

To be sure, the establishment of the Court of Appeals for Veterans’ Claims in 1988 (more precisely, its precedents) has gone a long way in upending this premise. Still, with only 6% of veterans’ benefits claims being appealed to the Court, the benefit to veterans at large remains in question (See more here). And although veterans’ benefits are very much at the discretion of Congress—with, after all, the lawmaking powers in the congress and the executive powers in the office of the president—they are far from being mere gratuities. Veterans’ benefits have long had among their purposes to reward and encourage service. In addition, president after president has urged veterans’ care as the nation’s obligation.

George Washington for one learned the hard way while in command of the Continental Army that recruitment and retention depend on the nation’s promise of care to those who served. By April 1778, Washington, Commander in Chief of the Continental Army, came to realize that “[soldiers] will not be persuaded to sacrifice all views of present interest, and encounter the numerous vicissitudes of War, in the defence of their Country, unless she will be generous enough on her part, to make a decent provision for their future support” (see more here). At war’s end in 1781 Washington bade farewell, noting “the obligations this Country is under, to that meritorious Class of veteran Non-commissioned Officers and Privates, who have been discharged for inability” (See more here). What Washington’s words conveyed was that veterans’ care was not only necessary to encourage service but also a matter of national obligation. Though notable among the leaders and lawmakers who have learned these lessons, he was not the first.

The tradition of state-funded veterans’ benefits in the United States traces to the time of Queen Elizabeth I and the defeat of the Spanish Armada. It was then that parliament passed the first modern veterans’ benefits law, which left no mystery as to its purposes:

[S]uch as have . . . adventured their lives and lost their limbs or disabled their bodies, or shall hereafter adventure their lives, lose their limbs, or disable their bodies, in defence and service of Her Majesty and the State, should at their return be relieved and rewarded to the end that they may reap the fruit of their good deservings, and others may be encouraged to perform the like endeavors; Be it enacted . . . .

Providing veterans’ care to reward and encourage service continued into the New World. A law passed in the British colony of Virginia in 1624 provided “[t]hat at the beginning of July next the inhabitants of every corporation shall fall upon their adjoyning Salvages, as we did last year . . .”—to fall upon their adjoyning Salvages meant to make war with the close-by natives—and that “[t]hose that shall be hurte upon service to be cured at the publique charge; in case any be lamed to be maintained by the country according to his person and quality.” Other colonies passed provisions that were similar.

In 1636, Plymouth Colony passed a law providing veterans’ benefits to encourage service against the Pequots: “[I]f any man shall be sent forth as a soldier and shall return maimed he shall be maintained competently by the Colony during his life.” As a law scholar observed, “This promise of relief was meant to encourage the colony’s soldiers against the Pequod Indians.” Similar laws sprang up in Maryland, New York, and Rhode Island, also to encourage service.

Over the course of the generation that followed the Revolutionary War, opinions of the war changed, and with them, opinions of the war’s veterans. Still, what endured was the idea of veterans’ care as a national obligation. By the time John Quincy Adams became the nation’s sixth president, he had much to say on the “duties” of the office, noting among them “the debt, rather of justice than gratitude, to the surviving warriors of the Revolutionary war,” and “the extension of the judicial administration of the Federal Government to those extensive and important members of the Union.”

In the era of national security, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) also reaffirmed the nation’s obligation to veterans. Ten years after he established the Board of Veterans’ Appeals, set up to make final decisions on veterans’ benefits claims, FDR delivered a radio address in 1943 on the mustering out of the veterans of World War Two: “May the Congress do its duty in this regard. The American people will insist on fulfilling this American obligation to the men and women in the armed forces who are winning this war for us.”

Other presidents have made similar statements over the course of U.S. history. The post-nine-eleven era is most notable. In this era, each president, Democrat and Republican, has made similar statements on the nation’s obligation to veterans. These statements are important. After all, as political scientist Harold Lasswell has urged (in the preface of the book What Washington Said: Administration Rhetoric and the Vietnam War 1949-1969): “[P]residential statements are political acts. When the president delivers a memorial eulogy in Arlington National Cemetery, he performs a ceremonial act of respect and gratitude, yet the political overtones are unmistakable. Clearly the nation’s power in the world arena is contingent on the support of those who put their lives on the line.”

With these political acts, presidents, Democrat and Republican, have spoken with one voice on the nation’s obligation to veterans, proclaiming, from this common ground, a common cause.

Notably, amid the United States’ divisions, on 9 February 2021, only a day after being sworn in as the new VA secretary, Denis McDonough noted an opportunity for unity, saying, “At this moment when our country must come together, caring for you – our country’s Veterans and your families – is a mission that can unite us all.” Presidents’ statements on the nation’s obligation to veterans show why he’s right.

Veterans’ care as a common cause follows from the concept of the common defense. Far from being only a government obligation, the imperative of veterans’ care is an obligation of the people. In the end, veterans’ care can unite us all, but only if we, the people, do the work.