Red Flags on the Map: What Soviet Kids Learned about the United States

My most treasured possession from more than a quarter century of travel in Asia cost me more to frame than to buy. It is a laminated Soviet-era middle school historical map of the United States for the period from 1870 to the beginning of World War I in 1914. I picked it up for less than $5.00 at a bookstore in Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, on the last day of my first working trip to Central Asia in December 1995, four years after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In the mid-1990s, there were no direct flights from Bishkek to European hub airports, and I didn’t relish the challenge of negotiating Moscow’s Sheremetyevo. My return flight to Frankfurt left from Almaty, the then-capital of Kazakhstan, a four-hour nighttime drive from Bishkek. Around midnight, the guards at the Kyrgyz-Kazakh border cursorily examined my passport, then waved the car through. With an icy wind blowing in from the north, they were more interested in returning to the warm stove in their guard post (and perhaps another shot of vodka) than going through my suitcase. At Almaty airport, however, the customs officials were alert, keen to explore what this foreigner was trying to take out of the country. One pulled out the map and unfolded it on the table.

“The export of valuable cultural artifacts including historical maps is strictly prohibited,” he solemnly informed me. In the dimly lit customs hall, I could not see his face and try to guess whether he was serious or just trying to solicit a bribe from an anxious traveler. I summoned up my limited Russian vocabulary and explained that this map was neither rare nor valuable. Maps like it had hung on schoolroom walls throughout the Soviet Union for decades. Perhaps he remembered it from his school years?

The officer shrugged. If I really wanted to take it, he said, then he would have to charge a special export license fee. We chatted amiably for a few more minutes before I came up with the winning argument.

“What do you think I’m going to do with a historical map?” I asked. “Use it to plan an invasion of the United States?” The officer and his colleagues got the joke. To save face, they confiscated a couple of knick-knacks, and sent me on my way.

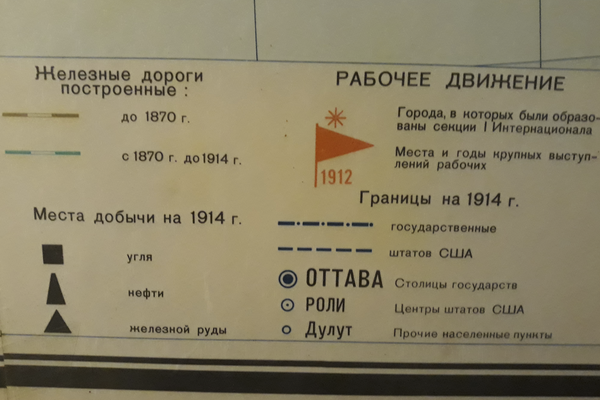

It was not until two years later, after returning from a Fulbright Fellowship in Kyrgyzstan and more than a year of Russian classes, that I studied the map in detail. It focuses on the US economy and population, with symbols showing the expansion of the railroad network and mineral deposits—coal (угля), oil (нефти), and iron ore (железной руды). The most prominent symbols on the map, larger than the circles denoting the population size of cities, are red flags. They pop up in cities and rural areas, with most in the northeast and Midwest.

Below each flag was a year, and that was my clue. Cities such as Buffalo, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Chicago, and St. Louis had two years listed, 1877 and 1886—these were the years of railroad strikes that were brutally suppressed. Pittsburgh, 1892—the Homestead Strike. Ludlow, Colorado, 1913—the miners’ strike. And so on. The legend identified the red flags collectively as “labor movement” (рабочее двжение--rabocheye dvijeniye).

The history of the United States was being taught to Soviet schoolchildren through the ideological lens of strikes and labor unrest. Shaded areas indicated Native American reservations, where indigenous peoples were, in the Soviet view, being oppressed and exploited. An inset map, entitled “Imperialist Aggression,” showed Central America, the Caribbean and East Asia, with nasty-looking black arrows indicating US military operations.

The map is interesting, not only because of the contrast it offers to the maps used to teach American middle-school students about their country’s history, but because of the not-so-subtle message it sends about borders. State borders are marked, but the states are simply classified into two groups: those that were part of the Union before 1870, and those that joined later, with no text explaining when or why they became states. The real borders on this map, as represented by the red flags and shaded areas, are class borders—between the capitalist bosses, supported by the federal, state, and local governments, and the working classes, between settlers and ranchers and the Native Americans, confined to their reservations.

It is a selective, ideological history, although perhaps no more so than the history of the Soviet Union as taught to US students (if it was taught at all). Working in Central Asia from the mid-1990s to 2012, I met many people whose view of US history was largely a catalog of class warfare, strikes and racial oppression. Lessons learned in middle and high school were amplified and reinforced by newspapers, TV, and films. In his March 1983 speech to the National Association of Evangelicals, President Ronald Reagan famously described the Soviet Union as the “Evil Empire,” a label that fit well with the preconception of many Americans at that time. They might be surprised to learn that many Soviet citizens also thought of the US as an evil empire, even if they did not use that phrase. In both societies, education and the media shaped the mental maps of its citizens.