Telling the Story of the "Ghost Children" of Germans who Plotted Against Hitler

I was excited.

I recognized the tell-tale signs of discovery after a decades-long career of sharing under-told stories from history with children and teens. Excitement, yes, and a sense that I’d found my next book. But this was something more. My latest discovery literally took my breath away.

Not only had I unearthed an episode of World War II history that had barely been told beyond Germany, I’d found one that was anchored by a little-known diary kept by a child eyewitness to the events. And she was still alive. And so were other “children” from this history. And I was going to be able to meet and interview them.

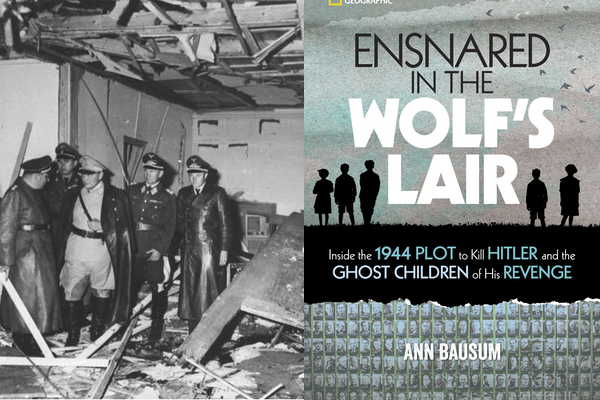

Their stories were intimately intertwined with a much better known occurrence: the Valkyrie coup attempt of July 20, 1944, that began with Claus von Stauffenberg’s efforts to kill Hitler at the dictator’s Wolfsschanze, or Wolf’s Lair, hideaway. Stauffenberg’s explosive device killed four men, but not Hitler, and the associated coup crumbled.

Within hours Stauffenberg and three associates had been executed by firing squad. Theirs were among the earliest deaths in a wave of retribution that would claim over 150 lives. But this trail of vengeance—embedded within the greater horror of the Holocaust—and as gruesome and unjust as it was, marked only the starting point for Hitler’s revenge.

That’s where the children came in. And the diary, and two research trips to Europe, and six years of alternating work and fermentation along the path toward creating Ensnared in the Wolf’s Lair: Inside the 1944 Plot to Kill Hitler and the Ghost Children of His Revenge (National Geographic Kids: 2021).

Children remained top of mind throughout my work—those who had experienced the past and those who would learn about it through my book. I was also concerned about the adults that my eyewitnesses had become. These people were in their 80s now or more. Most had dodged and battled with shadows of trauma for years, even a lifetime, and I didn’t want my project to become another triggering event. I would need to employ patience and discretion during our shared backward glance.

Context is everything when writing for children and teens. I assume a baseline knowledge of, well, nothing. The trick is to feather in a framework of understanding without overpowering the history-driven narrative. In order for my readers to empathize with the child protagonists in this book, they had to understand a wealth of background: how Hitler rose to power, the shifting nature of German resistance to his rule, World War II history, and the events of Valkyrie itself.

Opening chapters offer this context, but whenever possible I share information through the lens of the families that would become intertwined in Valkyrie and the punishments that followed. I particularly drew on the childhood memories of my interview subjects. I hoped readers would feel even more connected to history when viewing it through the eyes of an earlier cohort of children and young adults.

When I write, I aim to make the history feel personal, urgent, and irresistible. For this project I relied on historical facts, photographs, and eyewitness recollections to draw my audience into the drama of the events. I needed readers to comprehend how challenging and daring—and likely doomed—it was for the fathers of these children to try and overthrow Hitler’s regime.

Twelve-year-old Christa von Hofacker began keeping a diary shortly after her father’s arrest in Paris for his role in the attempted coup. No sooner did her father’s fate become uncertain than her mother’s did, too. And her older sister’s. And her older brother’s. All three family members were taken away by Gestapo agents with minimal explanation soon after her father’s arrest. Christa and her two younger siblings remained at home under a patchwork of care that included an unwelcomed Nazi state nurse.

Readers of Ensnared in the Wolf’s Lair know all about Christa and her family by the time these relatives start to go missing. They’ve been following them since the opening pages of the book with a growing sense of anxiety that makes the shock of their arrests that much more personal and distressing.

I was able to build these bridges between readers and subjects because of direct connections I’d been fortunate enough to establish with Christa. Using interviews, correspondence, and access to her diary, I could share her perspective through her childhood writings as well in statements made with a lifetime’s worth of lived experience and insight.

Similarly I was able to introduce readers to the memories of Berthold von Stauffenberg, the oldest son of Hitler’s would-be assassin, who was ten years old in 1944. During my second research trip in Germany I was fortunate enough to meet and interview him as well as Friedrich-Wilhelm (Friewi) von Hase, a retired professor who had been seven when his family became entangled in the aftermath of the failed coup.

Friewi’s older sister, Maria-Gisela, is now in her mid-nineties, but her memories of those years remained fresh during our conversations. She was twenty in 1944 and was among the older family members swept up in early Gestapo arrests. These relatives became pawns for use as leverage against the conspirators, faced interrogations of their own, and were generally terrorized by their extra-judicial captivities.

Younger family members experienced their own terror after they were removed from their parentless homes and spirited away to a remote compound for weeks or months on end. These girls and boys came to be known as the “ghost children” and were offered next to no explanation for their detentions or their fates.

The children spent weeks and even months in suspended animation at their hideaway in the Harz Mountains of central Germany. After older relatives began to be released from prison, they found it next to impossible to locate the missing youngsters, both because there was a war going on and because the children’s surnames had been changed to obscure their identities. Christa, Berthold, and twelve others remained in captivity when Allied forces reached the property on April 12, 1945.

These events are still living history for the children and young adults who have carried it with them into their senior years. They are also captured in the historical record through memoirs and letters from other eyewitnesses. My goal as an author was to transport new generations back to this era without losing the immediacy of those personal connections. Direct quotations from interviews, written accounts, and Christa’s diary are essential to that work, but so are my own memories from the research.

During my investigative travels I had seen the Wolf’s Lair and explored the grounds of the wartime complex where Hitler had been attacked. I’d visited the Borntal, too—the Harz Mountain property where Christa and other children were detained—and I’d even been permitted to wander the abandoned interior of one of their former residences. I also had memories of seeing the cities the children had known, the places where conspirators had been executed, the room where the coup had failed.

I infused my text with those details, too—and the emotions that accompanied them, from amazement at the grandeur of the lives these families had once led, to the paralyzing contrasts of the situations that followed, to the gritty terror of the places where the accused had been killed.

Lives are built around memories, emotions, and personal connections. So are histories. For me the best way to engage readers in the past is to bring it to life, to make it fresh, to create such tangible connections through text and illustrations that readers almost fall into the pages of the book and travel back in time.

I try to personalize the reading experience even further by capturing stories from the past that resonate in current times. Whether it’s the tutorial on the power of propaganda, or the account of the rise of a demagogue, or the conveyed terror of family separations, readers aren’t just learning about events from the past. They’re learning how to live in the present.

That’s something to get excited about, too.