"Juke": Bluesman Bobby Rush on the Roots of Rock and Roll

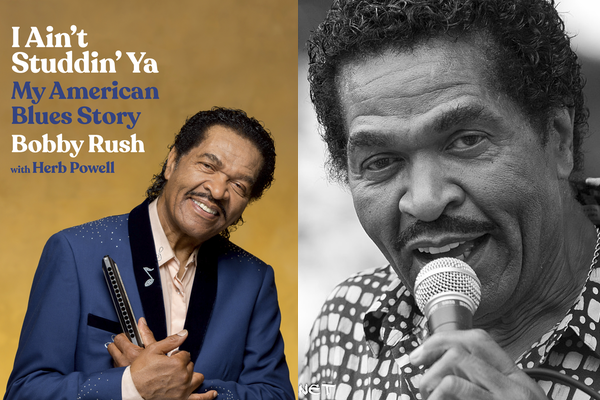

Cover image courtesy Hachette Books. Bobby Rush performs at Chicago Blues Festival, 2010. Photo Bryan Thompson, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0

The good Lord had planted me in the right place. For Pine Bluff, Arkansas, had lots of juke joints. There was Sturdik’s, the Elks Lodge, Drum’s, Nappy’s, the Jack Rabbit, and Jitterbug, where I got to first know Elmo James. In the early ’50s some juke joints had improved in the way they looked, while others looked like they hadn’t been touched since Negroes built them. Some didn’t even have indoor toilets.

Most of the jukes in Pine Bluff couldn’t hold more than a hundred people. Many were in the woods, off the beaten path. This was so the bootlegging and gambling and—sometimes—prostitution could take place freely. ’Cause the four Bs—the blues, booze, broads, and booty (money, not boo-tay)—were the magical mixture of people spending their paychecks, and that was the lifeblood of the juke joint hustle.

Still, music being the central attraction for most, we Black folks raised Cain to get into the juke joints. With delicious music, there was a feelin’ in the air of livin’ it up. Everybody is enjoying everybody else. Men picked up women and women picked up men. Some people were fully liquored up, and some just a little tipsy. Segregation was a way of life for us. But in juke joints we fixed onto being segregated. Being in the thick of ourselves with our own groove. The sights and sounds, the tastes and smells, were ours and ours alone. There was freedom in these places. But it doesn’t mean that jukes couldn’t get rowdy, especially on the weekends after payday.

But I would make a name for myself at Nappy’s and at a jumping spot in Altheimer, Arkansas, called the Busy Bee Cafe. Nappy’s was the first place I performed with a band, a microphone, and an amplifier. Just a drummer, upright bass player, and me. Nappy’s sat behind a big old sawmill. And like most juke joints, it didn’t look like anything from the outside. Just a frame dwelling with a front door and a back door. No windows. There were three of us, each paid 75 cents along with a plate of chitlins, a hot dog, and a hamburger. I sold my chitlins and my hamburger for 50 cents and ate my hot dog. I had $1.25. I was happy.

In my first gig at Nappy’s I was just that teenager with personality that could get the house goin’. Even though I was playing 90 percent of every song I knew in the same key, with a hard-finger-playing bassist and a drummer who could really snap, we grooved. And I played enough of the hits of the day to keep the party going. Louis Jordan’s “Saturday Night Fish Fry” and “Caledonia,” Johnny Otis’s “Double Crossing Blues” and “Cupid’s Boogie.” I blazed through Charles Brown’s classic “Trouble Blues” and Memphis Slim’s “Messin’ Around.” Those were great party songs. And with a few of my own ditties thrown in, I had a pretty bouncin’ set.

But this was late 1951, and there was one song that came out earlier in the year that I had to play in my set. And that was “Rocket 88” by Jackie Brenston & His Delta Cats. But for all intents and purposes, this was an Ike Turner record. It was his band and, although not credited, he wrote the song. That record changed everything. Most people say “Rocket 88” is the first rock ’n’ roll record, but as Ike Turner told me repeatedly for over forty years, “Bobbyrush, everybody knows that that’s a damn R&B record.”

R&B was very boogie-woogie influenced early on. But in terms of what they then called pop or popular music, that boogie-woogie sound was the opposite of the very calm and stuffy hit parade tunes. Hell, the big pop hits of 1951 were songs like “The Tennessee Waltz” by Patti Page, “Too Young” by Nat Cole, and “If” by Perry Como.

“Rocket 88” just turned the world upside down. Just like ten years before when the snap and pop of the jump blues sound swept young folks off their feet. The distorted guitar and sexual innuendo dripping from “Rocket 88” was too much for young Black and white kids to take. You felt that shit in your bones. It made you horny in a way that wasn’t all sexual. It had heat. It was literally a fresh feeling when I played that song from the stage. But no one could deny the smokin’ energy of “Rocket.”

I took Boyd Gilmore’s advice when he said, “You gotta git, boy,” and made it my religion. I went to every gig by every artist I could in Pine Bluff and the surrounding area. Saw everybody. From guys performing on the street to stars performing at big nightclubs and the little juke joints. I would do a lot of soaking at the Townsend Park Recreation center, or, as everybody called it, “Big Rec.”

Big Joe Turner was the first artist I saw at the Big Rec. This was before he had his hit record with “Shake, Rattle & Roll.” But he had popular songs everybody knew, like “Piney Town Blues.” Most of his grooves were boogie-woogie, and back then that was irresistible—you couldn’t help but bop your head. People that didn’t (or couldn’t) dance would just wiggle their first finger in time as he sang. The boss of the blues was light skinned like me and had a flawless slicked-back haircut. He looked to be three hundred pounds or more. Joe Turner wasn’t an outrageous performer; he just stood there and pointed every once in a while. But his voice was so commanding you couldn’t help but to focus on him. And when he’d stretch both of his arms far out to his side, he looked like a giant T. Big Joe was so big—it was as if he was wrapping the entire room up in his outstretched arms. I immediately copied that move into my performances. I also tried to copy something else.

To get my hair like his.

Excerpted from I AIN’T STUDDIN’ YA: My American Blues Story by Bobby Rush, with Herb Powell. Copyright © 2021. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.