Recessional: The WASP and God (excerpt)

St. John's Episcopal Church, Washington DC

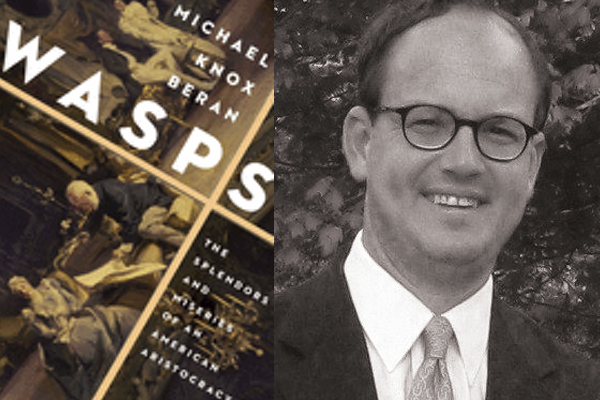

The following is excerpted from WASPS: The Splendors and Miseries of an American Aristocracy by Michael Knox Beran (Pegasus Books - August).

Bestemmiavano Dio . . .

They reviled God . . .

—Dante, Inferno

Of all the conditions of his youth which afterward puzzled the grown-up man,” Henry Adams wrote, “this disappearance of religion puzzled him most.” As a boy he “went to church twice every Sunday; he was taught to read his Bible, and he learned religious poetry by heart; he believed in a mild deism; he prayed; he went through all the forms; but neither to him nor to his brothers or sisters was religion real.”

That the “most powerful emotion of man, next to the sexual, should disappear” was a puzzle to Adams, though of course he exaggerated religion’s demise. If he heard only the “long, withdrawing roar” of God, the sea of faith was in fact quite real to many of his fellow WASPs in the first innings of the twentieth century. Isabella Stewart Gardner, Vida Scudder, Endicott Peabody, and Franklin Roosevelt, to name only a few, declined to be mourners in what Thomas Hardy called “God’s Funeral.” (Adams himself, we have seen, flirted with Catholic conversion in his dotage, spurred on by his friendship with Father Cyril Sigourney Fay.)1 The Authorized Version and the Book of Common Prayer were still part of the fabric of WASP life, but as the century wore on, God for many WASPs—probably indeed for most of them—ceased to be a faith and became instead a whimsy, an exercise in keeping up the forms.2

Yet there was an undercurrent of devotion. T. S. Eliot, WASP counterrevolutionary-in-chief, was probably the most illustrious figure in the resistance; he had gone to school to Dante, and when he recited the Athanasian Creed he meant every word. He wrote movingly of Dante’s ultimate apprehension, in Paradiso, of legato con amore in un volume, of divine love binding in one volume the scattered pages of the universe. It was a vision that embodied for him “a principle of order in the human soul, in society and in the universe.” Yet for all that something was missing in his idea of a Christian society; it was somehow colder, less caring, than, say, Cotty Peabody’s. His version of Anglo-Catholicism—in contrast to that of John Henry Newman at the height of the Oxford Movement—converted very few. Eliot was, at least until Anthony Julius threw the spotlight on his anti-Semitism in the nineties, the poet laureate of the WASPs; they all learned, in prep school, about J. Alfred Prufrock and the Objective Correlative. But they declined to take his Christianity seriously—to them it was he, with his faith, not they, in their want of it, who was “after strange gods”; and in the years since his death in 1965, they have gone in more and more for agnosticism, atheism, various travesties of Hinduism, Buddhism, Sufism, and the like, or (most characteristically) simple indifference.

What, then, of the fair sheepfold the WASPs sought, the image of their idea of regeneration? Was such a thing possible without God? T. S. Eliot, following Dante, said no. Henry James said yes: he does not portray Hyacinth Robinson’s conversion, in Venice, to humane culture as a religious awakening. Santayana took a position that differed from that of both. He did not believe in God, but he nevertheless believed that religion, as poetry intervening in life, had a part to play in a well-ordered community. “Always bear in mind,” he told his friend Daniel Cory, “that my naturalism does not exclude religion; on the contrary it allows for it. I mean that religion is the inevitable reaction of the imagination when confronted by the difficulties of a truculent world. It is normally local and always mythical, and it is morally true.” He was himself partial to the liturgies of Catholicism and high Anglicanism, poetries sufficiently rich at once to engage the imagination and to pacify it, reconciling it to life’s limitations even as it genially obscured life’s horrors.

We are today likely to think of ourselves as being compelled to check a box, as on a census form or a standardized test: religious, secular, or not sure. Santayana offers another possibility, that of the nonbeliever who yet recognizes the utility of religion. Some will dismiss his position as so much spiritual hermaphroditism, but he points to a compromise that would preserve our pluralism in matters of faith (and the denial of faith) but would not force us to resign ourselves to the sterility that characterizes a society in which all the most poignant spiritual poetry has been shut away. (It may be possible to get through life without Bach’s Mass in B Minor, but who would be willing to essay so dangerous an experiment?) You need not believe in Greek Orthodoxy to find the festival of the Virgin in a Greek village more life-enhancing than the tediousness of our own pedestrian civic calendar.3 Nor must you subscribe to the religion of the Koran to find the poetry of Fez a relief after the spiritual vacuity of New York. We interpret pluralism as a commandment to keep one’s religion out of the way; faith in public becomes, like farting in the same situation, a thing in bad taste. But it would do pluralism no harm and might do the body politic considerable good if the poetry of various spiritual disciplines were more palpably present in public space. Jefferson said that it did him no injury if his neighbor said there are twenty gods or no God. It does me no injury if I find the representatives of five or fifteen faiths making music in the public square. I am enriched by the music, whether it be that of the mass or the muezzin. It would be a great advantage if we were to encounter, in our daily rounds, spiritual wares as frequently as we do material ones: so many examples of longing and beatitude to counterbalance the monotony of getting and spending, the excessive worldliness that made Wordsworth say he would rather be a pagan suckled in a creed outworn than a modern Briton living in the shallows of her soul.

We may enjoy the poetry of the fair sheepfold without believing in the shepherd himself. But when we come to the achievement of the WASPs, their public service, their standards of conduct, their faith in the possibility of regeneration, we find that it owed a good deal to their conviction that there is a shepherd, a divinity that shapes our ends, rough hew them how we will. “He believes that he communicates with God and God communicates with him.” So Rebecca West said of Whittaker Chambers. Chambers was, according to his detractors, a crank: yet the words were no less true of Franklin Roosevelt, whom it is less easy to dismiss as a crank. “Why Harry,” Frances Perkins said to Harry Hopkins, “it’s clear that he’s got a relationship to God.” The idea of the good shepherd animated the little seminary in Massachusetts in which Roosevelt was educated, perhaps the most successful of WASP efforts to impress upon the soul the virtues of civic obligation and service to others. The “active love” that Endicott Peabody tried to make real for his boys—the same love that Alyosha, in Dostoevsky’s novel, tried to make real for his boys after the death of little Ilyusha—remained with many of them to the end:

And whatever happens to us in later life, even if we don’t meet for twenty years even if we are occupied with most important matters,

if we attain to honor and high place or fall into great misfortune— still let us remember how good it was once here, when we were all together, united by a good and kind feeling which made us, for the time we were loving that poor boy, better perhaps than we are . . .

1. A mentor to Scott Fitzgerald, Fay was the model for Monsignor Darcy in This Side of Paradise.

2. Joe Alsop, in his seventies, “wanted to begin going to church regularly once more,” for in his old age he found “church moving and rewarding.” He blamed his failure to do so on the barbarous iconoclasm of his age, one that shattered the poetry of the Authorized Version and the Book of Common Prayer. There “seems to be no church in Washington,” he wrote, “that regularly uses the King James version of the Bible or the magnificently lovely old Episcopal prayer book.” When he heard the liturgy in its new “castrated” form, he found himself, he said, committing “the sin of anger,” and was “out of temper for the rest of the day.” It should perhaps be added that, although he disliked religious enthusiasm and was contemptuous of the more saccharine forms of piety, when he lay dying in Georgetown in 1989, he was heard by his housekeeper to moan, “Is there a God?”

3. In Die Cultur der Renaissance in Italien, Jacob Burckhardt saw the old festivals as representing “a higher phase in the life of the people, in which its religious, moral, and poetical ideas took visible shape.” The festivals in their highest form “mark the point of transition from real life into the world of art.”