Richard J. Evans on Fascism, Today's Right, and Historical Truth

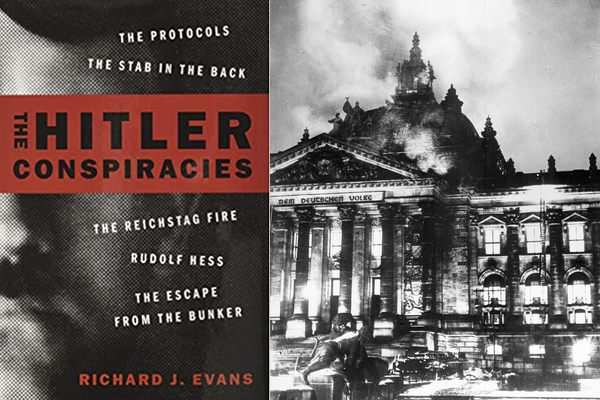

Historian Richard J. Evans is a preeminent scholar on Hitler and Nazi Germany, most pointedly through his trilogy on the history of the Third Reich. His most recent work, “The Hitler Conspiracies: The Stab in the Back - The Reichstag Fire - Rudolf Hess - The Escape from the Bunker,” takes on the key conspiracy theories generated out of the Hitler era. Aaron J. Leonard recently conducted an interview with him via email to discuss his work, the current invoking of fascism in some quarters, and the contrast between solid historiography and work amplifying and propagating conspiracy theories.

________________

Why do you think Hitler and his murderous regime — which ought to be repellent — loom so large in the popular imagination?

They loom so large in the public imagination precisely because they are so repellent. Hitler has come to stand as a kind of substitute for Satan in an increasingly secular world: he is the epitome of evil. When we think of Hitler, we think of dictatorship, war and genocide, of cultural repression, racism and the looting of art on an unprecedented scale. The more the Holocaust has become part of mainstream public memory, the more it has brought Hitler into the center of public attention as its originator.

Your chapter detailing the “Stab in the Back” myth, which claims the German army was sabotaged from victory in World War I by various anti-patriotic left-wing forces, made me think of a Vietnam veteran I encountered a few years back who was adamant that in that war, the US was forced to fight with ‘one hand tied behind its back.’ It seems one of the features of many of these conspiracy theories or ‘alternative histories’ is to take a loss or weakness, and turn it into something less. Is that accurate, or is there something else going on?

The idea that a war – or an election – wasn’t really lost, but betrayed by a backstairs conspiracy, is an easy and perennially attractive way (to some people at least) of explaining defeat: defeat, after all, is very difficult and painful to admit. It also disqualifies a whole section of society as not really part of it, whether that’s the Jews or the socialists in Germany in 1918, or the Democrats in America in 2020.

In your book Lying About Hitler — which recounts the libel suit brought by David Irving against historian Deborah Lipstadt, a trial in which you testified — you literally had to chase down footnotes to show how he manipulated evidence to minimize and deny the Holocaust. Irving is arguably more insidious than some of those you challenge in your current work because he was seen as a scholar, rather than a crackpot — and yet, his methodology is not far removed from the crassest of conspiracists. How would you contrast the two methods employed between conspiracy-based ones – which are not wholly devoid of evidence — versus those based on the method of honest historians?

Conspiracy theorists very frequently imitate the methods of honest historians: You will find their works weighed down with footnotes and crammed with elaborate, solid-looking detail. Only when you subject them to detailed scrutiny does it become clear that the detail isn’t solid at all – it’s full of deliberate errors, falsifications, manipulations, misquotations, mistranslations, calculated omissions and manufactured connections, speculation, innuendo and supposition. Irving’s Holocaust denial work was full of mistakes, as the judge in the libel action he brought against Deborah Lipstadt in 2000 noted, but they were not honest mistakes, since they all went to support his arguments. Honest mistakes are random in their effect; his were not. Honest historians know they have to abandon their arguments when the evidence turns out to disprove them; dishonest historians and conspiracy theorists bend the evidence to fit the argument.

Quite a few people, particularly on the left, have taken to invoking the word ‘fascism’ or otherwise draw parallels to the National Socialists of the 1930s & 40s, to describe various current phenomena. What do you see as the limits – and benefits if any — of such historical analogies?

Fascism is one of those concepts that can seem almost infinitely elastic; it’s just too tempting for polemical purposes to accuse any authoritarian politician of being like Hitler, or any populist movement of being fascist. But we have to remember that fascism was a militaristic movement, aiming at war and conflict, territorial expansion and empire. Fascists put every citizen into uniform, drilled the people into uniformity and obedience in training camps, and subordinated private life, business companies, and institutions of all kinds to the state. Fascists were ultimately genocidal, whether it was the Nazis exterminating the Jews, or the Italian Fascists exterminating the Ethiopians (among other things, by using poison gas). Nazism and Fascism also put science at the center of their belief systems, in particular, racial and eugenic ‘science’, and regarded religion as a leftover from medieval times that would soon disappear. In all these respects it differed from 21st-century populism, which is hostile to the state, anti-scientific, and opposed to militarism both within the country and outside it. The classic fascist mass consisted of endless marching columns of identically uniformed men; today’s populist mass, as in the storming of the US Capitol on January 6th, 2021, consist of thousands of informally and in some cases eccentrically attired individuals heaving about in a chaotic heap, violent and aggressive but not organized in any military way. The problem with calling today’s right populism ‘fascist’ is that it’s fighting today’s battles with the weapons of the 1920s and 1930s. Time has moved on since then.

I am constantly astonished, and not a little frustrated, that so much taken for ‘common knowledge’ has already been countered by professional historians and yet it seems we live in a world where too often “alternative history” operates as actual history in the popular imagination. How can that ever change, or at least not command such power?

The Internet and social media are largely though not exclusively responsible for undermining belief in truth and objectivity. Society has become increasingly polarized through the rise of ‘identity politics’ – my truth is not the same as your truth (though in fact there can never be two opposing truths; only one of them can ever be the real truth). The spread of hyper-relativism through the dominance in universities of postmodernist culture has also played its part. The mass media, above all television and the movie, have blurred the boundaries between truth and fiction. Holding social media companies to account for the lies they allow to be spread is a beginning. But more needs to be done.