Richmond's Lee Statue Has Come Down. What About Confederate Memorials in Cemeteries?

The State of Virginia concluded one of the last battles of the Civil War on September 8 when it finally removed the statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee from Monument Avenue in Richmond. Workers sawed the statue in half at the waist, leaving the stately general as a mere torso without a horse or legs.

The controversy has been in the news for several years now, as communities and states try to figure out what to do with monuments to dead Confederates erected more than a century ago. Some argue that these statues should be preserved since they commemorate so-called heroes of a glorious, albeit unsuccessful, campaign, the “Lost Cause.” Others rightly assert that those monuments represent an ideology supporting racial inequality and a false narrative of the history of Civil War and its causes.

Immediately after the war, southerners tried to come to grips with having lost the war and more than quarter of a million men. They rationalized the war by asserting that it was fought by patriots defending both states’ rights established by the founding fathers and a social order that stood on the enslavement of a race they deemed congenitally inferior and happily enslaved. They erected statues and monuments as one way to reinforce those ideas. Their descendants sought to shape the collective memory of the war in highly visible ways.

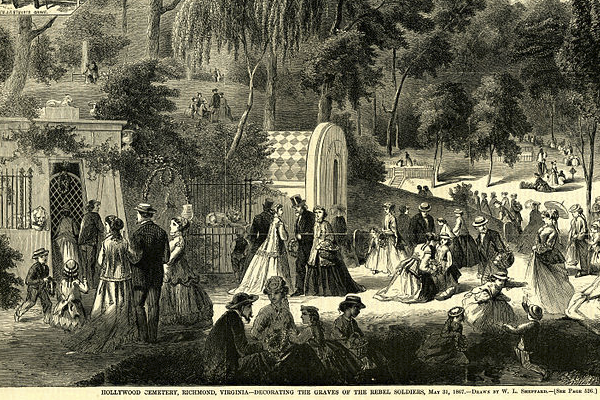

Beginning in 1865, Ladies Memorial Associations worked across the south to consolidate the burial locations of men from their communities, sometimes in existing cemeteries, sometimes in newly created ones. In Richmond, they relocated the remains of more than six hundred dead Confederates from the Gettysburg National Cemetery. They interred them with some 18,000 others around a ninety-foot-tall stone pyramid adjacent to Hollywood Cemetery, dedicated in 1869.

Cemeteries were an essential tool in the Lost Cause toolbox. This was in part because people had come to think of them as more than burial spaces alone starting in the 1830s. These new “rural cemeteries” like Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Laurel Hill in Philadelphia, and Hollywood in Richmond were landscaped spaces with rolling hills, winding roads and paths, and verdant landscapes where people visited to stroll and escape cities, like the ways people use urban parks now. Their gravestones and monuments made sure people remembered who was prominent by their locations and size. Laurel Hill Cemetery founder John Jay Smith wrote that “thus does the rural cemetery ensure a double chance for good or great names being remembered first on a stone tablet, and next on the ever more enduring page.”

Lost Cause proponents politicized the idea of “good or great names.” They began erecting monuments to the Civil War dead in cemeteries in part because they knew people visited them. More importantly, they were places where people mourned the dead and buried their remains, making them sacred spaces in the popular mind as well. Thus, they sanctified the message of the Lost Cause by association with such places. And that’s what gives them extra power to convey messages.

Sheer size gives some of these monuments even more influence. The one on Confederate Circle in Nashville’s Mount Olivet Cemetery includes a nine-foot-tall soldier surveying the area from some forty-five feet overhead. The engraving on one side notes that “this column sentinels each soldier’s grave as a shrine.” The dedication in 1889 was so large with thousands attending that the city closed for the afternoon, making it a de facto holiday.

Similarly, thousands attended the dedication of the famous “Lion of the Confederacy” sculpture in Atlanta’s Oakland Cemetery. An American artist plagiarized the wounded lion lying on a Confederate flag from a massive sculpture in Lucerne, Switzerland. In the dedication ceremony, the Rev. I. S. Hopkins clearly linked the Lost Cause with the spiritual. “May the time never come,” he prayed, “when the cause for which they died will be less sacred.” When Col. John Milledge spoke at the same event, he wondered aloud “why this righteous cause should have failed, God in His wisdom only knows.” They consciously used speeches given in a hallowed space to sanctify the message of the Lost Cause.

Even though statues like the one of Lee (now formerly) on Monument Avenue were large and prominent reminders of the Lost Cause Ideology, proponents may or may not have known that civic objects can be removed as times change. They clearly realized that such was not necessarily the case with those in cemeteries. They reinforced this the relationship between the sacred space where the dead still lie and the intrinsic messages of the markers of commemoration with every Memorial Day gathering. They understood that removing a monument in a sacred space such as a cemetery is something that, in our society, is simply not done. Even in Richmond, the statue of Confederate General A. P. Hill still stands at Laburnum Avenue and Heritage Road, some six miles from Lee’s former pedestal. It remains not because it’s less offensive, but because his remains are buried there (removed from Hollywood Cemetery in 1892), sanctifying the space in the popular mind.

So, the removal of the Lee statue has been one battle in the war to end the Civil War, but not the last. Others remain. Other cities, other statues. But the most difficult to remove will be those in cemeteries that stand in spaces regarded as sacred, above the mortal remains of the fallen.