The Strangely Forgettable Burial Place of Henry VIII

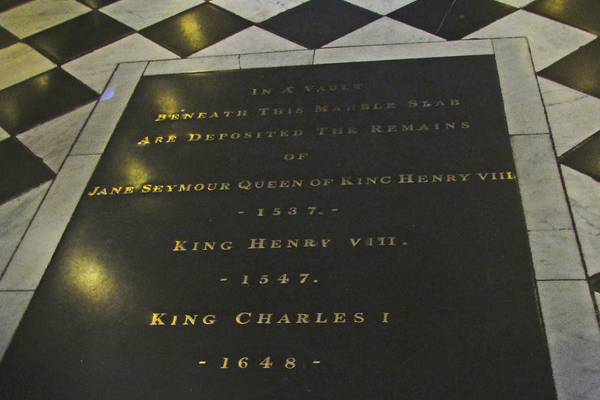

Burial marker, St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle

A black marble slab marks Henry VIII’s final resting place in the quire of St. Georges Chapel, Windsor Castle. However, this was only intended to be temporary while a grand monument was completed, and it was clear that no expense was to be spared. Henry laid down an elaborate plan to portray himself on horseback in armor, emulating the iconic image of the medieval knight. The Tudor king also wanted to be remembered within a chivalrous setting, choosing to be buried at St George’s Chapel, the location for the Order of the Garter Ceremonies. Designed to seal his reputation as a great and glorious warrior king, if completed, his tomb would have surpassed everything of its kind in England.

Yet Henry’s magnificent plans for his tomb were never followed. He was not a king, or a man to be ignored, so why were his memorial wishes? Perhaps Henry was showing a rare frugality, recognizing his country was impoverished from his war ambitions in France, and his plans for his burial tomb were grandiose and expensive. The other likelihood is that Henry, who had an aversion to accepting his own mortality, did not want to tempt fate by having his effigy completed during his reign. Henry had grandiose ideas when it came to designing other royal burials. The effigies of his grandmother Lady Margaret Beaufort and his parents Henry VII and Elizabeth of York were each made of magnificent gilt bronze and laid to rest in Henry VII’s Lady Chapel, at Westminster Abbey. This makes it all the more surprising that all that is provided for the king at St. George’s Chapel is a slab of black marble.

The initial plan for Henry’s tomb was not realized, and so he set out making new designs with the help of Italian sculptor Jacopo Sansovino in 1527. Henry commissioned an extraordinary 75,000 ducats for this elaborate design, a modern equivalent of six million ninety thousand pounds! The details of the final resting place for Henry VIII were written in a document entitled “The manner of the tomb to be made for the kings grace at Windsor,” yet unfortunately this manuscript no longer survives. However, luckily it was transcribed in the seventeenth century by antiquarian John Speed in his History of Britain, which gives details of Sansovino’s design that were followed up until the king’s death. It is Henry’s planned effigy that is the most striking, as his burial tomb was to be topped with a life-size gilded statue of the king on horseback under a triumphal arch, “over the height of the Basement shall be made an Image of the King on Horse-backe, lively in Armor like a King, after the antique manner.” Throughout his kingship Henry was deliberate in his fashioning of knightly masculinity, thus his elaborate design to have himself depicted on horseback, in armor emulating the archetype of the medieval knight was intended to bolster this manly portrayal.

The figure of the king on horseback also had strong imperial overtones that fitted Henry’s ambitions for conquest and imperial expansion in France. This military drive harkened back to a golden age of chivalry, with its high point being under Edward III and Henry V who had established English settlements in Normandy and Calais. From the start of his reign Henry held ambitions for reconquering France; he had always wanted to pursue his claim for the French throne as far as he could, while establishing international prestige as a celebrated military leader. The king’s invasion of France in 1513 achieved only modest success, yet it was still a remarkable achievement given that it was England’s first victory in France within living memory. Although modern historians have treated Henry’s triumph with some contempt, at the time he was perceived as a successful warrior king, and his tomb was intended to reflect this status.

Though Henry’s ambitious plans for his tomb may have highlighted Renaissance modernity, the king’s choice of burial at the chivalric setting of St. George’s Chapel symbolized the coming together of the medieval past with the present. Henry clearly identified with his medieval ancestors as he left precise instructions about the repositioning and beautification of the tombs of Henry VI and Edward IV, thus immortalising himself as the living embodiment of the two houses of Lancaster and York. It was Henry’s grandfather, Edward IV, who had commissioned the building of a new chapel for St. George in 1475, which was completed by his grandson in 1528. Significantly, Edward IV was the first monarch who chose to be buried at St. George’s Chapel, rather than at Westminster, evidencing his close alignment with chivalry. It was also Edward IV who provided a significant platform for jousting contests in the 1460s, as he chose to compete alongside his men in the tiltyard. Henry was also actively involved in chivalry, like his grandfather, taking part in jousting contests from the start of his reign and being invested with Order of the Garter at the age of four. St. George was also known to be Henry’s idol, which may explain why the king selected to be buried at St. George’s, rather than at Westminster with his father.

It is surprising that more has not been made of Henry VIII’s planned tomb, despite it never being completed, as it is still important to consider how the king wanted to be remembered. There is much we can learn about how Henry understood his kingship and masculinity from the design of his effigy, which was planned to venerate him as a medieval knight in armour on horseback. Yet, it is indeed ironic that a king who decided on an extravagant and oversized effigy, who held spectacular jousting tournaments, hosted a glamorous Tudor court, and who led a glorious campaign to France, should lie in a plain vault, marked only by a black marble slab.