On the Illogic of War

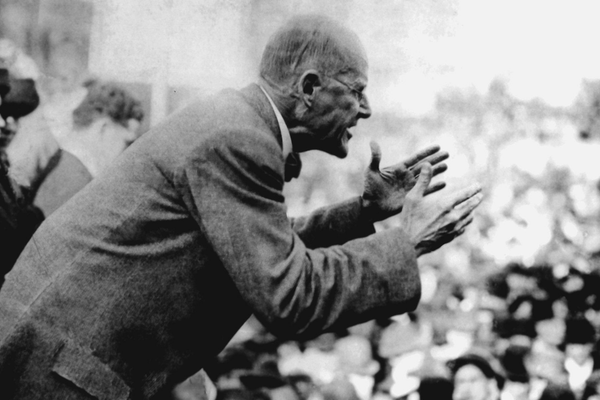

Socialist and Pacifist Eugene Debs speaks in Canton, Ohio in 1918, shortly before his arrest under the new Sedition Act.

The scenes are horrific. Russian soldiers indiscriminately or intentionally killing Ukrainian civilians. A maternity hospital and high-rise apartments bombed by the Russian military. Women and children fleeing to Poland and other countries while men form themselves into militia units. We see it happening before our eyes, broadcast by 24-hour news channels. Its hard to believe this is happening in the middle of the European continent in the early 21st century.

Meanwhile, in Russia, Putin continues his disinformation campaign, claiming he is attempting to de-nazify Ukraine. It’s a bizarre claim, not least because the president of that country, Volodymyr Zelensky, is Jewish and has ancestors who died in the Holocaust. Putin is in the process of a systematic attempt to control all coverage of the war, shutting down independent media and violating civil liberties by making it illegal to even mention the war in Ukraine. On state-run media the war is described as a “special operation” designed to protect Russian-speaking Ukrainians, many of whom have become refugees due to the war. There is little mention of the death and destruction being rained down on the innocent people of Ukraine.

During these horrors, it is important to remember history. It is not just autocratic governments that deny civil liberties or kill civilians during war. The logic of war pushes even open democratic societies to engage in measures that are considered, with hindsight, as abhorrent. We in this country sometimes think we’re immune from such occurrences, but it has happened in the United States as well.

One of the first incidents occurred early in our history. In the late 1790’s the United States under President John Adams had become engaged in what became known as the Quasi-War with France. The fear of a French invasion was real. French warships were patrolling off the coast, and American vessels were captured in New York harbor. It was in this context that Congress approved the formation of a large army. The Federalists also passed a series of measures that became known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. The most clearly partisan of the measures was the Sedition Act that was passed in July of 1798, when our nation became engaged in its own attempt to violate civil liberties and limit free speech. That Act made it a crime to speak or publish “any false, scandalous, and malicious writings against the United States, or either House of the Congress of the United States, with intent to defame…or to bring them…into contempt or disrepute…” The Sedition Act was clearly directed at the opposition Republicans, making it essentially illegal to criticize the government, in violation of the First Amendment. The fever finally broke when Jefferson was elected president in 1800, although it took 36 ballots in the House to break a tie between him and his vice-presidential running mate, Aaron Burr.

Perhaps one can excuse this incident in American history since it was early in the creation of the nation and Constitutional protections for free speech had not been firmly established. The same cannot be said for the action of the Wilson administration during World War I. The Congress passed three bills that restricted the civil liberties of Americans, including the Espionage Act, the Alien Act and the Sedition Act. The latter banned “uttering, printing, writing, or publishing any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” against the military or the government. As the historian John Milton Cooper has written of Wilson, violations of civil liberties during the war “left the ugliest blot on his record as president.” Both England and France also engaged in ever more egregious acts of repression of their citizens.

None of this should be construed as in any way sanctioning what Russia is doing in Ukraine. Yet war has a logic (or illogic) of its own. As Clausewitz wrote: “War is an act of force, and there is no logical limit to the application of that force.” He thought that political goals would place limitations around war. But as Jonathan Schell wrote in his book The Unconquerable World, the First World War saw “the logic of war triumph over the logic of politics.” Both sides used weapons of mass destruction, in this case mustard gas, on each other. And monarchies in Russia, Germany, and Austria all fell.

World War II saw further atrocities. Before the United States entered the war in 1939, Roosevelt had warned the participants that “under no circumstances undertake the bombardment from air of civilian populations or of unfortified cities.” Early in the war, our military was sensitive to British “area bombing” on moral grounds, since it allowed for “civilian areas near industrial and transportation centers,” to be included, James Caroll writes in his book entitled House of War. Not everyone in the American military agreed, with then colonel Curtis LeMay saying: “To worry about the morality of what we are doing---Nuts.” LeMay was perfectly expressing the logic of war and by 1943 the United States abandoned its position and began the firebombing of German and Japanese cities culminating in the use of nuclear weapons against Japan.

Of course, there are real differences between the role of the United States in World War II and what the Russians are doing in Ukraine. In World War II, the United States was attacked by Imperial Japan and went to war to stop aggression by both them and Nazi Germany. Russia is the clear aggressor in Ukraine, with Putin violating the sovereignty of an independent state. And while the U.S. agonized over its decision to inflict civilian casualties in World War II, Putin jumped to this step almost as soon as his invasion began to fail.

Jonathan Schell has argued that nuclear weapons have made unlimited war unimaginable. But the war in Ukraine has not gone as well as Putin hoped. Perhaps he has forgotten Clausewitz’s warning, that a war “cannot be considered to have ended so long as the enemy’s will has not been broken…” The great fear is Putin will move beyond his current approach of destroying Ukraine with conventional weapons and turn to the use of chemical or biological weapons. God forbid he go that far, or introduce the use of nuclear weapons. If that happens, then even Schell’s hope for limitations on war go out the window, and we may be facing the ultimate conflagration.