In Ukraine, the US Likely to Follow Kissinger's Example and Disappoint Idealists

Supporters of Ukraine, like these demonstrators in Boston on Feb. 27, 2022, are likely to be disappointed by any peace deal. Vincent Ricci/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Jeffrey Fields, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

The U.S. has limited options in confronting Russia over its invasion of Ukraine.

The Biden administration’s strategy is moderated by what’s known as “realpolitik.” The U.S. is not willing to risk a larger war with Russia by any level of involvement that might bring Washington and its allies into direct military conflict with Moscow, risking an escalation into nuclear war.

In a recent column for The Washington Post, journalist Matt Bai lamented that President Joe Biden “will be forced to take a realpolitik view that most of us will find hard to stomach.”

“No matter how unjust Ukraine’s fate, he must continue to reject any measure that threatens to put U.S. troops in direct conflict with the Russians,” Bai wrote.

This means that, even as much of the world decries the savagery of the Russian invasion and the intense suffering of Ukrainians, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s call for efforts like a NATO-enforced no-fly zone will go unanswered by both Washington and NATO allies.

And, as a scholar and practitioner of U.S. foreign policy, I believe any agreement produced by peace talks between Ukraine and Russia will reflect the U.S. realpolitik approach and likely disappoint Ukraine’s supporters.

President Richard Nixon, left, and Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai toast each other at the end of Nixon’s first day of his visit to the People’s Republic of China on Feb. 21, 1972. AP Photo/Bob Daugherty

The costs of realpolitik

What exactly does realpolitik mean?

Realpolitik refers to the philosophy of states’ pursuing foreign policies that further their national interest, even at the expense of human rights, or compromising intrinsic liberal values in pursuit of their interests abroad.

In the U.S., you can’t discuss realpolitik without referring to the foreign policy of U.S. President Richard Nixon, guided by his national security adviser and later secretary of state, Henry Kissinger. The two men, in the most audacious example of their practice of realpolitik, set in motion events that led to normalized relations with China. President Nixon put aside his virulent anti-communist leanings in favor of an approach he hoped would ultimately strengthen the U.S.

Yet Kissinger dismisses the notion that he is or was a proponent of realpolitik.

“Let me say a word about realpolitik, just for clarification. I regularly get accused of conducting realpolitik. I don’t think I have ever used that term. It is a way by which critics want to label me,” Kissinger told German news magazine Der Spiegel in 2009.

Yet later in the interview, Kissinger sounds like the realpolitik practitioner he is frequently characterized as:

“The idealists are presumed to be the noble people, and the power-oriented people are the ones that cause all the world’s trouble. But I believe more suffering has been caused by prophets than by statesmen. For me, a sensible definition of realpolitik is to say there are objective circumstances without which foreign policy cannot be conducted. To try to deal with the fate of nations without looking at the circumstances with which they have to deal is escapism. The art of good foreign policy is to understand and to take into consideration the values of a society, to realize them at the outer limit of the possible.”

In essence, Kissinger is not arguing for a foreign policy devoid of morality. Instead, he believes in recognizing the limits of furthering the national interest if policy is circumscribed by idealism.

To contain communism meant engaging in foreign policies that contradicted “traditional” American values of respect for human rights and self-determination. To Nixon and Kissinger, winning the Vietnam War, or at least ending it in a way the American public would find acceptable, meant taking unsavory actions, including carpet-bombing Cambodia.

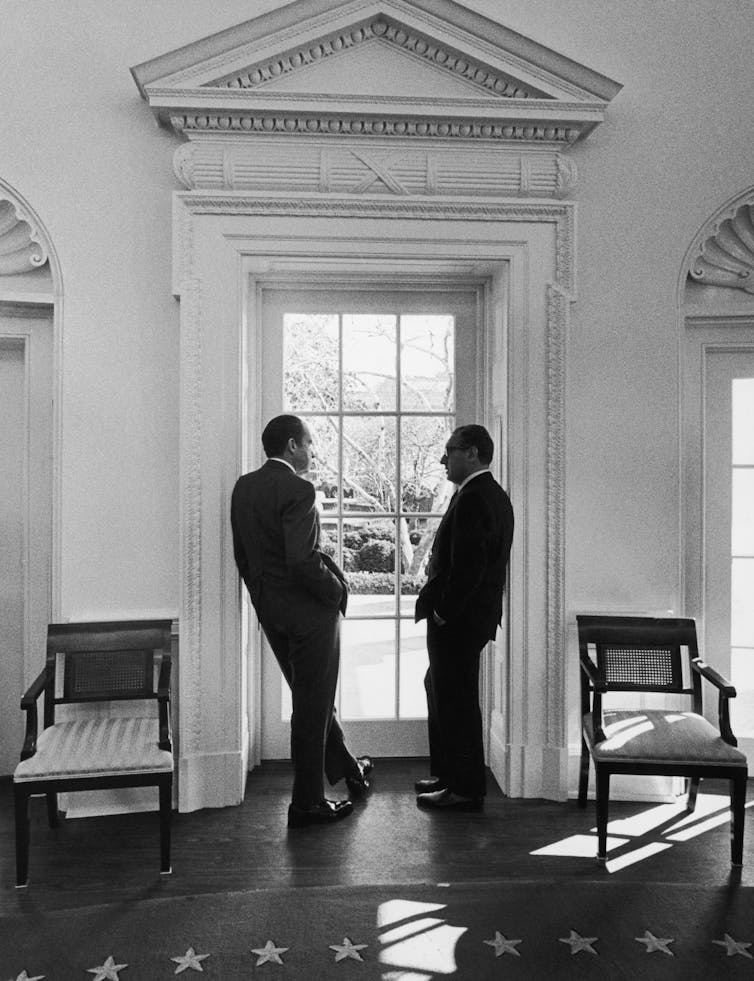

President Richard Nixon, left, with U.S. National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger in 1972. Frederic Lewis/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Containing communism also translated into support for the dictator and human rights violator Augusto Pinochet in Chile during Kissinger’s tenure. Post-Kissinger, realpolitik meant support for right-wing anti-communist dictators in Central America during the Reagan administration.

Realpolitik without guns

Realpolitik isn’t only about the justification and conduct of wars. Nixon and Kissinger also sought to exploit the emerging rift between the Soviet Union and China. They made the decision to try to improve relations with China, which had been almost nonexistent since the Chinese Communists defeated the U.S.-backed nationalists in 1949. Their efforts culminated in Nixon’s historic visit to China in 1972.

The staunch anti-communist in Richard Nixon believed improved relations with China served the national interest, further driving a wedge between Beijing and Moscow and setting the course for a safer world, in perhaps a generation.

To set this in motion meant backtracking from his – and many Americans’ – anti-communist leanings. Ideology took a back seat to pursuit of the national interest.

The U.S. views itself as a proponent of universal human rights, democracy and the rule of law, self-determination and sovereignty of nations. But not at the expense of its own global position. At times, domestic politics can influence adventurism abroad and how strongly American values are incorporated into foreign policy. There are times when Americans are angry and want to see an adversary punished even if it means violating the nation’s ideals.

Public sentiment after the 9/11 attacks, for example, gave President George W. Bush wide latitude in foreign policy. But as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan stretched on, the American public’s appetite for the wars and overseas policing diminished greatly, forcing Presidents Obama, Trump and Biden to bring the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to an end without a clear victory, leaving behind unstable nations.

Chilean dictator President Augusto Pinochet, left, greets Secretary of State Henry Kissinger at the president’s office on June 8, 1976. Bettmann/Getty

How the Ukraine war ends

What will the end of the Ukraine war look like?

Realpolitik in American foreign policy means restraint in Ukraine. A direct confrontation with Russia is not in the U.S. interest, and Ukraine’s strategic value is limited. An illegitimate war in which hundreds if not thousands of Ukrainian civilians have already been killed won’t move the U.S. away from this position, because the risks of escalation are too high. And nuclear escalation would be likely, because the U.S. is far superior to Russia in terms of nonnuclear forces.

Without the U.S. and NATO engaging militarily in the war, Ukraine will likely be forced to make concessions and accept at least some terms that Russia wants in any peace agreement. That may include a Ukraine with different territorial borders and a security relationship with Russia that it does not entirely like.

This may be hard for some – both inside and outside Ukraine – to stomach. But however much realpolitik is attributed to a Kissinger-dominated era of history, it has been and still is present in contemporary U.S. foreign policy.

From tacit support of the murderous dictator Saddam Hussein in the Iran-Iraq War – in which the U.S. knew of Saddam’s use of chemical weapons – to letting Afghanistan fall into a political vacuum after the Soviet pullout in 1989 – leading to the rise of the Taliban – to Washington’s close relationship with brutal human rights abuser Saudi Arabia, the U.S. frequently chooses to put its own interest ahead of its professed values.

[There’s plenty of opinion out there. We supply facts and analysis, based in research. Get The Conversation’s Politics Weekly.]

Jeffrey Fields, Associate Professor of the Practice of International Relations, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.