"Two-Spirit" Visibility and the Year Activists Rewrote History

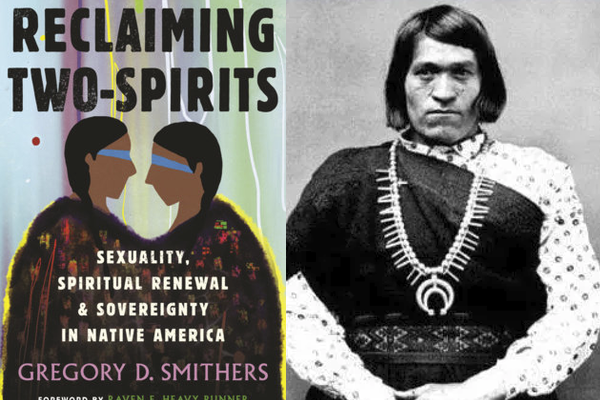

Pictured at right is We'wha (1849-1896), of the Zuni nation. Popularly known at the time as "The Zuni Man-Woman," We'wha might today be described with the modern term "Two-Spirits"

March 31 marked the International Transgender Day of Visibility. Founded in 2009 by Rachel Crandall, a transgender activist from Michigan, this annual event has filled the silences in our nation’s history with stories of transgender accomplishments, struggles, and love. Crandall wanted to draw the public’s attention to the richness and complexity of the people represented by the “T” in LGBTQ life. In 2021, as state lawmakers across the country began drafting anti-transgender bills, president Biden rewarded Crandall’s efforts with a White House proclamation to “honor and celebrate the achievements and resiliency of transgender individuals and communities.”

In 2022, International Transgender Day of Visibility coincided with efforts to pass anti-transgender legislation at the state level, and rising violence against trans people – particularly trans people of color. Faced with such bigotry, it has never been more important to celebrate Crandall’s activism and the efforts of transgender people to raise their visibility throughout the United States. Refusing to remain silent, transgender people continue to play a major role in reshaping modern American history. That work builds on the dedication and persistence of previous generations of transgender people. In fact, transgender visibility was once a routine facet of healthy, nurturing communities that pre-dated European colonialism in North America.

During the summer of 1990, a small group of Native Americans wanted to reclaim that history. Roughly 100 people – gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender – gathered at campgrounds just north of Winnipeg, Manitoba, on August 1. This was only the third time they’d met for what they dubbed their “spiritual gathering.” The first two events, held in Minneapolis and at a campground in northern Wisconsin, laid the foundations for an annual event that attracted people from New York to California, Ontario to British Columbia. By the time participants packed up their Winnipeg campsite and headed home on August 5, none could have anticipated the ripple effects that the third gathering would have on the course of North American history.

At Winnipeg, a new term was born: Two-Spirit. An umbrella term, Two-Spirit is an English translation of the North Algonquin niizh manitoag. For centuries, Algonquin-speaking communities in Canada and the United States had referred to people embodying both feminine and masculine spirits as niizh manitoag. The English translation – Two-Spirit – replaced offensive colonial terms such as “berdache” and “transvestite,” and added depth to labels like “gay,” “lesbian,” or “trans” that didn’t capture the totality of a Native person’s spiritual identity. Two-Spirit provided that language. More verb than noun, Two-Spirit identities aren’t static, marginal, or locked in the past. They’re modern, innovative, and part of living traditions that millions of Native people continue to renew every day.

History is made up of moments like those at Winnipeg in 1990. These moments help us to make sense of things that happened, and are happening, to us and our loved ones. But history’s more than that – it’s more than a list of dates, names, and events. History’s also something we do. The Two-Spirit participants at the Winnipeg gathering highlight how history’s an active process that Native people were determined to rewrite. No longer would they allow the silences of colonial archives to strip them of their humanity or permit historians to mischaracterize their history and culture. At Winnipeg, Two-Spirit people were doing history on their terms. In agreeing to embrace the term Two-Spirit, the Winnipeg delegates became the authors of a transformative history. Just how significant was this historical moment?

In a word, it was transformative. Prior to the Winnipeg gathering, Two-Spirit people had labels placed on them by non-indigenous people. “Berdache,” the most commonly used label, pleased no one in Indian Country. It derived its origins from the Arabic word “Bardaj,” meaning a “kept boy” or “slave.” Like other popular labels – “hermaphrodite;” “transvestite;” “sodomite” – European colonizers used “berdache” as a slur; it defined Two-Spirit people as deviant, sinful, and worthy only of ridicule, marginalization, and in some cases, violent death.

Violence has many forms, and the participants at the Winnipeg gathering knew that they and their ancestors had spent centuries navigating physical and psychological violence. Public celebrations of American nationalism compounded the hurt. Holidays commemorating the 4th of July, Thanksgiving, and until recently, “Columbus Day” became ritualized features of the American calendar. For many Native people, these commemorative events felt like cruel exercises in emotional abuse. They also perpetuated historical mythologies that celebrated colonizers (white men, mostly) and silenced Native people (and made Two-Spirit people invisible).

At Winnipeg in 1990, Two-Spirit people flipped the historical script. In fact, they started writing their own scripts. At that time, historians continued to remain shamefully silent about Two-Spirit histories. Those who did write about Two-Spirit people in the 1990s followed a familiar narrative, portraying Two-Spirits as marginal or deviant figures in Native American history.

Two-Spirit people had had enough. Tired of historical misrepresentation, they’d write their own histories. Richard La Fortune (Anguksuar) made a major contribution to these efforts. La Fortune’s personal papers are now preserved in the Archives and Special Collections Library at the University of Minnesota. On the eve of the Winnipeg gathering, though, La Fortune had a message for the world: “We are everywhere.” La Fortune, a Two-Spirit Yupik man, captured the spirit that people brought with them to the Winnipeg gathering when he celebrated how “we’re reappearing with all of our own memories and traditions, our focus on culture and spirituality, sobriety, and political goals.”

La Fortune’s soaring prose matched the pride participants at the Winnipeg gathering felt during the warm August days in 1990. In the months after the gathering, Two-Spirit people reflected on their experiences. They expressed feelings of love, pride, and solidarity. Above all, they wrote of the joy they felt at taking control of their own historical narratives. History, and historians, would no longer mischaracterize or silence them. As one Two-Spirit delegate recalled in Two Eagles, a Native American newspaper, the Winnipeg “gathering was more a ceremony than just a gathering and sharing. All that was seen, all that was said, all that was shared, all that was done was ceremonial. We are a people whose time has come.”

In the years since the Winnipeg gathering, the term Two-Spirit has gained growing levels of acceptance across North America. Two-Spirit has become a staple of scholarly, educational, and journalistic writing. LGBTQ politics has also expanded to include “2S” people, and healthcare providers have recognized the importance of being attentive to the needs of Two-Spirit people. This visibility is a direct result of Two-Spirit people doing history. In the three decades since the Winnipeg gathering, Two-Spirit people haven’t let history happen to them; they’ve actively authored new historical chapters, and in the process, have changed how all Americans perceive them. It’s not necessary to wait for the next International Transgender Day of Visibility to join La Fortune and celebrate that Two-Spirit people “are everywhere.”