A Century After its Dedication, the Lincoln Memorial's Meaning is Still Contested

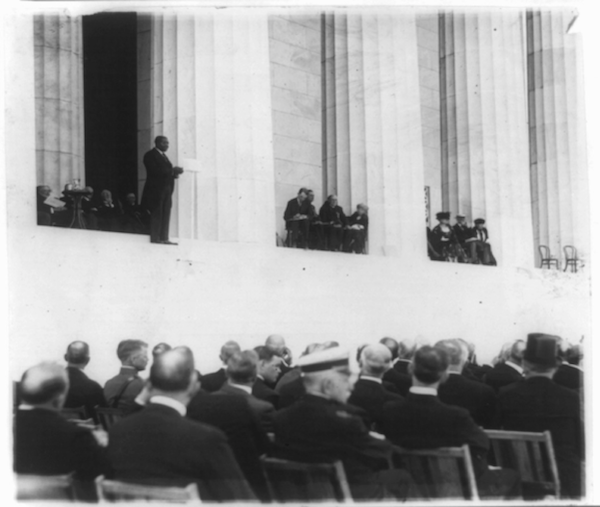

Tuskegee Institute President Robert Moton speaks at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial, May 30, 1922.

Photo Library of Congress

One hundred years ago, on May 30, 1922, a black man stood on the lip of the Lincoln Memorial and told the sea of mostly white faces in front of him about a ship that docked in Jamestown, Virginia in 1619.

The occasion was the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial, and the speaker was Robert Moton, president of the Tuskegee Institute and the most prominent African American of his day. Moton took as his task to remind the 50,000 in attendance, whose small black contingent was roped off in a segregated space, of the shared values of equality and freedom that Lincoln had espoused for all races in words engraved onto the Memorial’s walls behind the speaker.

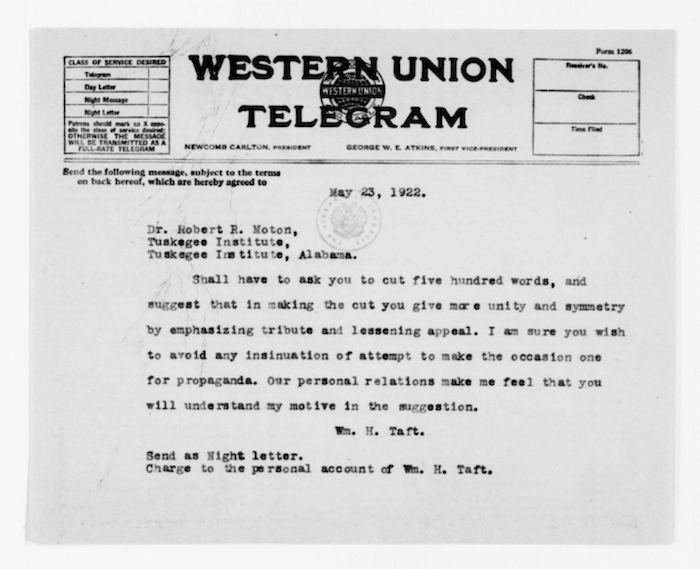

The times were intensely, openly racist, and Chief Justice William Howard Taft, the chair of the memorial commission, warned off Moton from some of his more pointed remarks about shortcomings in the progress toward racial equality. That he could speak at all, even in muted tones, was a tribute to Moton’s courage and persistence.

Moton opened by noting that one year before “the pioneers of freedom” were brought to America on the Mayflower in 1620, “another ship had already arrived at Jamestown … [with] the pioneers of bondage, a bondage degrading alike to body, mind and spirit.”

“Here then,” he continued, “upon American soil within a year, met the two great forces that were to shape the destiny of the nation. They developed side by side. Freedom was the great compelling force that dominated all, and like a great and shining light, beckoned the oppressed of every nation to the hospitality of these shores. But slavery like a brittle thread was woven year by year into the fabric of the nation’s life.”

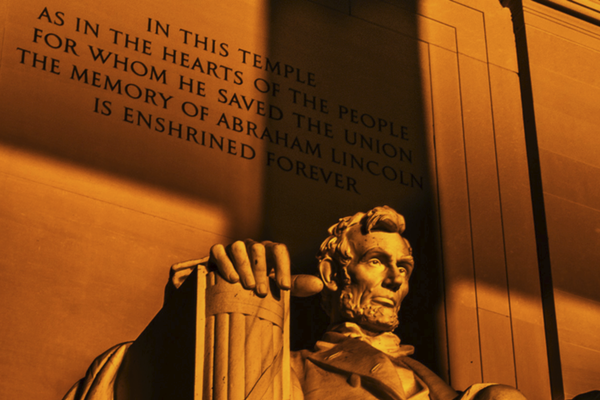

The other speakers that day, Chief Justice Taft and President Warren Harding, asserted that Lincoln’s greatness lay in preserving the union. Indeed, the words “he saved the union” were carved on the wall behind Lincoln’s head. Moton had a different view, and he made his point using the Gettysburg address, also carved in its full text onto the memorial’s south inside wall:

“the claim of greatness for Abraham Lincoln lies in this, that amid doubt and distrust, against the counsel of chosen advisors, in the hour of the nation’s utter peril, he put his trust in God and spoke the word that gave freedom to a race, and vindicated the honor of a nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

Yet some of the most passionate words in Moton’s first draft were never uttered that day, and survived only because he saved his manuscript after Taft told him that roughly 500 words deemed by Taft to be “propaganda” had to be cut. Gone, for example, was this passage:

No more can the nation endure half privileged and half repressed; half educated and half uneducated; half protected and half unprotected; half prosperous and half in poverty; half in health and half in sickness; half content and half in discontent; yes, half free and half yet in bondage.

Cut too:

I say unto you that this memorial which we erect in token of our veneration is but a hollow mockery, a symbol of hypocrisy, unless we together can make real in our national life, in every state and in every section, the things for which he died.

And he penciled out from his closing some of his most challenging language. Speaking, he would have said, for “twelve million black men and women in this country [who] are proud of their American citizenship,” he immediately intended to add:

but they are determined that it shall mean for them no less than for any other group… We ask no special privileges; we claim no superior title; but we do expect in loyal cooperation with all true lovers of our common country to do our full share in lifting our country above reproach and saving her flag from stain or humiliation.

All of that was cut, but he did close with these words reworked from the ending of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural:

With malice toward none, with charity for all we dedicate ourselves and our posterity, with you and yours, to finish the work which he so nobly began, to make America an example for all the world of equal justice and equal opportunity for all.

The day’s other main speakers mostly ignored or rebuked Moton’s theme. Taft, the former president and current chief justice, said nothing about slavery or emancipation and appealed instead to white southerners, who were prominently represented at the ceremony by a group of gray-clad Confederate veterans sitting in a place of honor near the front. The dedication of the memorial, Taft said, “marks the restoration of the brotherly love of the two sections in this memorial of one who is as dear to the hearts of the South as to those of the North.” Had Lincoln not been assassinated, he said, “the consequences of the war would not have been as hard for them to bear, the wounds would have been more easily healed, the trying days of reconstruction would have been softened.”

Photo by author

For his part, president Warren Harding asserted that Lincoln would have compromised with the South, allowing slavery to continue as long as it was not extended into new territories. He added: “Hating human slavery as he did, he doubtless believed in its ultimate abolition through the developing conscience of the American people, but he would have been the last man in the republic to resort to arms to effect its abolition. Emancipation was a means to the great end—maintained union and nationality. Here was the great purpose, here the towering hope, here the supreme faith.”

The design and materials of the Lincoln Memorial carried out the Taft and Harding vision of unification in ways both subtle and plain. The building itself, designed by Henry Bacon, was a Greek temple modeled on the Parthenon, its classic lines intended to convey timeless and universal truths. Marbles from both North and South were used: white from Georgia for Lincoln’s 19-foot-tall statue, pink from Tennessee for the floor of the chamber, white from Colorado for the giant fluted Doric columns that circled the exterior – 36 in number, one for each state of the union as of 1865, including southern states. The only acknowledgement of emancipation came in a mural, high on the wall above the inscribed Gettysburg Address, depicting the Angel of Truth freeing a group of African-robed slaves from their shackles.

That the Memorial displayed even this image, and that a black man was invited to give the keynote address for the dedication, showed at least modest steps toward confronting the legacy of slavery. The 1920s, after all, saw the peak of the “scientific” eugenics movement, with state-ordered sterilizations of women deemed “feebleminded,” and a great majority of states outlawing interracial marriage through “racial integrity” statutes. A month after the Lincoln dedication, a filibuster in the United States Senate killed an anti-lynching bill passed by the House. In 1925, 30,000 white-robed members of the Ku Klux Klan marched down Pennsylvania Avenue, and the only criticism mustered in the local press was that their marching formations were less than precise. The public schools of the nation’s capital were strictly segregated, and Post Offices and Treasury Department facilities had race-separate bathrooms and lunchrooms, a cancellation of Reconstruction-era integration ushered in by President Wilson while the Lincoln Memorial was under construction on a reclaimed mud flat of the Potomac River.

From its dedication to the present, the meaning and legacy of Lincoln and his memorial have been the focus of struggle between those who see Lincoln as the savior of the Union and those who claim him as the great emancipator. Snubbed and insulted at the Memorial’s dedication, civil rights leaders looked for opportunities to turn the public stage of the Memorial and its terraces into a platform for protest. On Easter Sunday 1939, after being turned away from the concert hall of the Daughters of American Revolution, Marian Anderson stood only a few steps from where Moton had spoken and sang “my country ‘tis of thee,” with Lincoln’s statue looming over her shoulder. And today visitors stand on the block of granite, on the first terrace in front of the chamber’s floor, etched with King’s words from his August 1963 speech, “I have a dream.” But millions of tourists come each year with no other purpose than watching the ducks on the Reflecting Pool or having their photos taken for weddings, graduations and reunions.

Those who step inside the Memorial and turn to their right can read Lincoln’s own answer about the meaning of the war and his legacy. In his Second Inaugural address, given on March 4, 1865, five weeks before the surrender at Appomattox, he said:

If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which in the providence of God must needs come but which having continued through His appointed time He now wills to remove and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him. Fondly do we hope ~ fervently do we pray ~ that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword as was said three thousand years ago so still it must be said 'the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.