Excerpt: The Fires of Stavishche, 1919

PROLOGUE: Stavishche: June 15-16, 1919

As dusk fell, a near full moon shone over Stavishche. Isaac and his wife, Rebecca, enjoyed a break from a long workweek, relaxing and celebrating with friends under the moonlight in a courtyard garden. Suddenly, the air erupted with nearby gunshots: Rebecca was panic-stricken. A man ran by and yelled, “Zhelezniak’s thugs! They’re back! There’s more of them—hide!” before dashing away. At almost the same moment, a woman screamed, “Please, no!” A child cried; a plate-glass window crashed. Thugs were bashing in doors and

destroying the Jewish shops and homes. Many, like theirs, were attached to both sides of the Stavishcha Inn, behind which they now sat frozen in fear.

“The girls!” Rebecca yelled. The thought of her daughters unfroze her, and she bolted toward the house. Another woman screamed, this time just across the courtyard wall. They were too close. Isaac grabbed his wife’s arm hard, pulling her to her knees. “There’s no time! Root cellar!”

They were just steps from the inn’s cellar, a half-dugout, musty hole under the crumbling corner of the old stables. Here, in the dark, they kept potatoes, bins of dried beans, hanging herbs. The cellar was cool and black. It felt dank and smelled slightly rotten, a hundred years of cobwebs, termite-infested rafters, manure, spilled pickle juice, and mildew. Isaac climbed down and wiggled to the back on his stomach; his wife did more of a crawl, protecting her growing belly from scraping the ground. Their hearts thumped as they lay with their arms around each other. A body thudded against Rebecca: it was her friend Rachel, followed by Rachel’s new husband, Elias.

The shots were more muffled now but still clearly nearby. The never-ending sounds jostled them: crashes of window glass, smashed liquor bottles, boots stomping, splintering of wood as doors were axed open, and then more gunshots. They heard the wild laughter of a group of drunken men.

“Our babies,” Isaac said in her ear. “I have to go get them.”

“It’s too late,” Rebecca whispered back.

Her hand tightened on his arm. “No!” she cried to him, knowing it was the cruelest word. “They’ll see us. They’ll follow us to the children. We’ll all die.”

From outside, more crashes, screams, laughter.

What have I done? Isaac thought, regretting his decision to leave the girls alone in the house.

Rebecca feared the worst. We’ve lost them forever, she thought. The dank root cellar would surely be their own grave; she knew it.

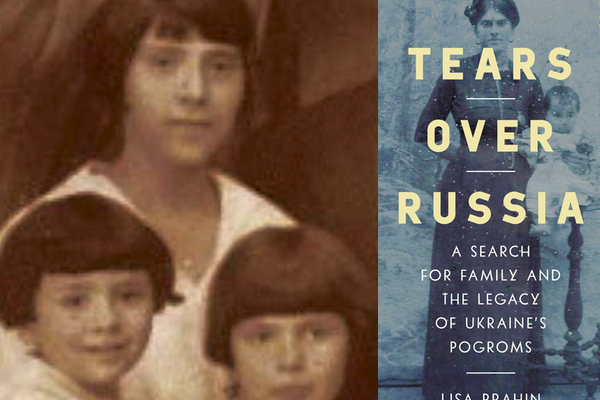

Just minutes earlier, the couple’s evening had begun peacefully. The near full moon meant that the night’s sky would never get completely dark. Yet this longer day of sunlight meant that Rebecca’s sewing continued well into the evening. It was Sunday, just before eight, when the pretty seamstress finally tucked her girls into their small bed in the back room, telling them, “Go to sleep now.” Slightly plump little Sunny, nearly three, snuggled her back against her six-year-old sister, Channa.

Rebecca moved quickly through the tiny living quarters, finishing her chores before heading out of the house. She took only a moment to fix her long, dark hair. Isaac was just arriving from the front room, set up as his shoe factory, where all day long he’d nailed soles onto boots. Sundays were especially long since the day before was Sabbath. Rebecca exchanged a weary smile with her handsome, dark-haired husband.

“The children are asleep?” he asked.

“On their way.”

The couple headed to the courtyard garden out back, near the stables that housed the horses for the guests at the nearby establishment. In a far corner, their neighbors Rachel and Elias, just married, sat and held hands on a bench. Isaac and Rebecca greeted their new friends with a bottle of wine. “Mazel tov!” they wished them, as the foursome raised and clinked together Rebecca’s silver shot glasses in a celebratory toast. Rebecca, resting her hand on her pregnant belly, did not raise the cup to her lips.

The courtyard was still and warm; a late spring dusk appeared. From the street they heard the clop-clop of horse-drawn wagons. They drank and laughed until most of the daylight disappeared after nine.

Inside, in the dark back bedroom, Channa snuggled her sister’s warm body until Sunny stopped wiggling. Then, feeling warm in the June evening, Channa kicked off the blanket and stared at the ceiling. Finally, she, too, dozed off: first fitfully, then so deeply that she didn’t hear the initial gunshots in front of the Stavishcha Inn.

The explosion had their parents sitting bolt upright: Rebecca’s round blue eyes widening, Isaac’s clean-shaven chin jutting from his face. Rachel screamed; Elias covered her mouth.

They waited in the root cellar. Hours of it; it would never end.

As daylight approached, the noises changed. First the commotion stopped. Rebecca and Isaac still lay in place, breathing lightly in rhythm, too afraid to move. Then the screams began again, but these were different: wails by the injured, wails for the dead.

The foursome crawled and then climbed out of the cellar and into the early June sun. From every corner, the neighborhood was coming out of hiding, hugging and crying or screaming next to the victims of the pogrom. Rebecca and Isaac ran quickly to their house. They opened the back door, which was still closed and intact, and rushed to their daughters’ bed.

Their legs froze in place, preparing for the worst. Rebecca felt an awful pit in her stomach, afraid of what horrible scene they might find. Instead, Channa lay peacefully on her back, and, as usual, her arms were outstretched. Sunny lay in a fetal position, her face pressed into the goose-feathered pillow. But they were breathing. They were sleeping, untouched. They’d slept through it all!

The violent mob had passed over their house!

Rebecca looked at her husband. His cheeks had gone white. Hands shaking, he picked up Sunny, who stretched and smiled. Rebecca broke down and sobbed uncontrollably into Channa’s long, brown hair. Confused, the girls looked around with wide eyes. Everything was exactly as Rebecca had left it: a soaking pot still stood upright on its stand, sewing needles and a small jewel case left on a nightstand remained undisturbed. The girls were oblivious to what had happened.

“Nothing—nothing touched,” Isaac said; wondering, “Why did they

spare us?”

“Isaac!” a howl came from outside the front door, followed by loud banging. “Isaac! Isaac Caprove! Your peasant Vasyl has murdered my wife!”

The Fires in Stavishche

In the spring of 1920, 1,500 to 2,000 Jews were burned alive in the synagogue in the nearby city of Tetiev by the followers of Ataman A. Kurovsky, a former

officer under Symon Petliura. The Caprove family, Isaac, Rebecca and their daughters, who had fled the shtetl after a previous attack, heard rumors from the safety of their apartment in Belaya Tserkov that these hooligans were headed toward Stavishche. By then, the majority of Jews who still remained in the town were the sick, disabled, and elderly. The spiritual leaders and their families also remained behind in support of their people who were unable to flee. A group of vicious local peasants entered Stavishche on the heels of Kurovsky’s men, who had left the shtetl as quickly as they entered it. On a beautiful spring day, these bandits set a few buildings on fire in the Jewish quarter of town.

Havah Zaslawsky, the devoted daughter of Rabbi Pitsie Avram, ran down the street in panic during the fires in search of her father, fearing that he had been killed. When she saw the flames rise near the synagogue (probably the Sokolovka kloyz, one of six in town), Havah instinctively knew that her father had rushed to open the ark for the last time. The rabbi, with his flowing white beard and large sunken eyes, suddenly emerged from the burning synagogue cradling his sacred Torah, its breastplate, and a pair of matching antique silver Torah crowns. The tiny bells that hung in layers from the priceless keters (crowns) jingled as he ran for his life.

Escaping the flames of the fires that spread quickly behind them, Pitsie Avram and his youngest daughter fled down the street together, meeting up with other family members along the way. At the Jewish Bikur Holim (Home for the Aged Hospital), six elderly female and two male residents were slaughtered. In the home of Shlomo Zalman Frankel, thugs tied him to a pig and set both on fire.

As the rabbi’s group fled, they were unaware as murderers searched house to house for Jews and tore the screaming, bedridden, and elderly from their beds. Within minutes they herded twenty-six Jews to another synagogue and slit their throats. Barking dogs began eating away at the dead.

At yet another Stavishche house of worship, Cantor David-Yosel Moser was inside chanting words from his precious Torah when bandits stormed in and confiscated his sacred scroll. Tossing the fragile parchment across the floor, the thugs then raped a Jewish woman on top of its pages. When that was not sufficient enough in their drunken minds to desecrate the holy scrolls, they brought in a horse to defile it.

Cantor David-Yosel stood helpless as the assassins torched his Sefer Torah (Torah scroll). Finally, the old chazzan’s heart gave out. He dropped to the floor, dying beside the thing that he loved most in the world. The old cantor, who in happier times loved entertaining the children of Stavishche by cutting out beautiful parchment chains of paper birds, died beside his burning Torah. This destruction, however, could not kill the spirit of either, for the spirit of the chazzan David-Yosel and his parchment scroll are both indestructible; they are eternal, beyond time.