Stephen Aron's Work Examines Moments of Intercultural Peace in the West

Few museum directors find the time to write books and even fewer write history books – yet Stephen Aron, President and CEO of the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, has managed this feat with a provocative new history of the American frontier

Founded in 1987 by Jackie and Gene Autry, the museum merged with the historic Southwest Museum in 2003 and its collection now contains more than 600,000 objects, including one of the largest collections of Native American artifacts in the U.S.

Before taking the position at the Autry, Aron was a professor of history at UCLA. His formal affiliation with the Autry began in 2002, when UCLA allowed him to split his appointment and become Executive Director of the Autry’s newly created Institute for the Study of the American West. In July 2021 he was named President and CEO.

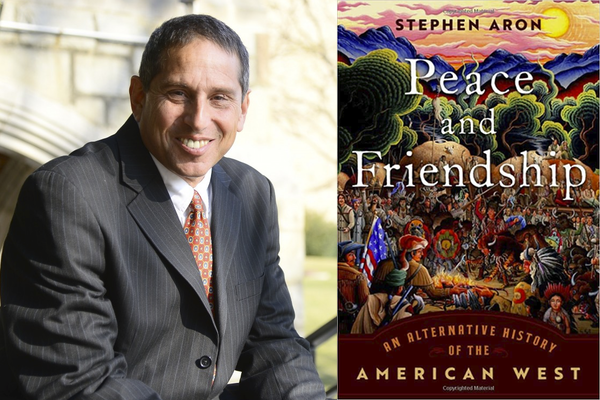

Aron is the author or co-author of four previous books including The American West: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford). His latest book, Peace and Friendship: An Alternative History of the American West (Oxford) examines episodes of peaceful accommodation, often overlooked in the dominant historical narrative of conquest and violence.

James Thornton Harris spoke with Aron about his new book and his role as the Autry’s CEO.

Q. In your book, you often use the term “wishstory.” What do you mean by that?

I define it as the history we wish for, often rather than what actually took place. Wishstories play to our desire for a feel-good version of American history and figure prominently in our popular culture. Consider, for example, the 1995 film Pocahontas made by Disney.

The movie invents a fairytale romance between John Smith and the young princess. They get married and, as is often the case in wishtories, are presumed to live happily ever after. That, of course, is not what happened for her or for her people. But the Disney version gave us intercultural accommodation, mutual understanding, and even interracial union. That is why it resonated so powerfully in the culture at that moment.

I should note that although I came up with the term several years ago, I have since found, through Google, that it was used once in a Sears Christmas ad that ran on TV in 2004. However, I believe I am the first to apply it in a historical context.

Q. Your new book focuses on five specific places including: Chillicothe, OH; Chimney Rock, NE; Dodge City, KS and Fort Clatsop, OR. Why these places?

When I took the position at the Autry, I decided to focus the book on the first century of the American Republic. I chose these places because they presented examples of how peace and sometimes even friendships prevailed—for a time—instead of the usual violence and subjugation that occurred in the settling of the American frontier. There are plenty of other places and moments that one could point to, but I chose these because I could create a thread from one to the next and I could draw on my own previous research to make that threading.

Q. Why focus on moments of peace and friendship?

For most of the 20th century, the dominant narrative of the American West was one of triumphant conquest, of brave settlers pushing out inferior native peoples. This expansion fulfilled our “manifest destiny.” In this telling, it is what American great.

In recent decades, that narrative has been inverted as writers and educators have come to decry the violence that was central to the settling of the West. The new narrative emphasizes colonialism, settler violence and exploitation, sometimes even genocide of native peoples. Recent histories detail the cost of colonial expansion both on the people who were dispossessed and on the environments that were despoiled. As a result, many historic events the public once perceived as “feel good” stories have been displaced by “feel guilty” stories. But whether celebrated or lamented, violence maintained its centrality in old and newer western histories.

The title of my book is meant to be provocative. It certainly cuts against the grain of the longstanding and current understandings about how the West came to be American. In contrast to the dominant narrative, the book’s contents show that there were times and places where varying degrees of peace and even friendship prevailed between settlers and natives

The episodes suggest that it is possible for two competing, sometimes warring, groups to reach peaceful accommodations. I wanted to explain how individuals and people overcame their differences as opposed to being overcome by them. And to see what we might learn from these places.

Q. Dodge, Kansas is a place many people have heard about. What happened there?

Of all the places I write about Dodge would seem the least likely to qualify for entry into a book called Peace and Friendship. Dodge City is the site we most associate with the “Wild West.” Even 150 years after its heyday as a cattle town, it remains a metaphor for uncontrolled violence and rampant disorder.

Now that story is not completely wrong. When the future city was a just a frontier outpost and center for buffalo hunting, there was a lot of violence. But shortly after cattle replaced bison as the town’s economic raison d’etre, the town’s leaders moved to restrict the carrying of guns. Despite uneven enforcement, the new laws worked in dramatically reducing homicides. And to my knowledge, no disarmed cowboy claimed a right to keep bearing their arms based on the Second Amendment.

With the popularity of “westerns” in the movies and on television, certain colorful characters such as Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp became famous and Dodge City once again became associated with gunfights and violence. Today, as the town seeks to attract tourists, the business leaders are playing up the association with Wyatt Earp and the wild west and still stage gunfights at the Boot Hill Museum.

Stephen Aron, CEO of the Autry Museum, shows one of the items that introduces the museum’s latest exhibition, “Dress Codes.”

Q. How has your work at the Autry Museum influenced you? And what are your goals now that you are CEO?

During my initial years at the Autry, when I was splitting my time with UCLA, it opened my eyes to wider possibilities, to how, through the museum, I could make history more accessible and more meaningful. I also saw that it was possible to make history more public facing and more present minded.

Now as the CEO of the museum, I want to further its mission to make the history of the West more accessible and to emphasize that this region is a place of convergence. It is where various cultures have mixed and mingled and influenced each other.

The history of the West was once based on the triumphant narrative of conquest by white settlers. We now understand that was based upon the exclusion and suppression of many other points of view. We need to actively seek out and make visible the histories that have been erased, silenced, or ignored.

When we bring together the stories of all the peoples involved in the West and start conversations with one another, we learn that the past is not distant but entwined with the here and now. Then we can come together to envision our shared future.