The Wartime Service and Postwar Activism of One Latino Veteran

Henry Romo, in Leyte Island. Photo found in the 1990s by Henry Romo, Jr.

All photos accompanying this essay from Ricardo Romo collection.

On Veterans Day every November 11, we recognize the men and women who have served our country in war and in peacetime. World War II stands out as a particularly challenging period when well-coordinated and well-armed armies led by sociopathic leaders of Germany, Japan, and Italy threatened the very existence of the Western civilization.

My dad, Enrique [Henry] Romo served in World War II and seventy-five years ago he stored a batch of his war photos in a small cigar box at the bottom of my mom’s cedar chest. Until three weeks ago, I had never seen these pictures, and my mom, Alicia Saenz Romo, never mentioned the box of photos. Several other photos were placed in a small bag which we discovered a few years before he died in 2005.

My dad, Henry Romo, with a captured Japanese flag.

The cigar box photos are unusual because they show soldiers in various combat zones in the Pacific theater, combat activities the soldiers could not have shared until after the war. But even after the war, some of the veterans chose not to discuss their experiences. The account of why many veterans kept the military experiences to themselves says much about the horrors of war and the desire to put those difficult times behind them.

World War II required a massive mobilization effort. Millions of Americans, whether engaged in essential duties of manufacturing arms and equipment or active in fierce naval, air, or ground battles, contributed to a victorious outcome for the Allied Forces. Many who served in the U.S. military returned to their homes after the war committed to the economic and political development as well as civic betterment of their communities. Others who had fought valiantly lost their lives in this conflict.

My dad, along with thousands of American soldiers fighting in the Pacific region, witnessed some of the bloodiest battles of the war. Military historians estimate that more than 30 million soldiers and civilians were killed in the Pacific conflict during the course of WWII, compared with 15 million to 20 million killed in the conflict in Europe.

Journalist Tom Brokaw’s prize winning book The Greatest Generation is a brilliant account of men and women “who came of age during the Great Depression and the Second World War and went on to build modern America.” Brokaw interviewed hundreds of veterans who served in World War II and concluded that the generation “was united not only by a common purpose, but also by common values--duty, honor, economy, courage, service, love of family and country, and, above all, responsibility for oneself.”

Henry Romo on a bombed out railway car.

My dad is one of those Americans who answered the call, as Brokaw described, “to save the world from the two most powerful and ruthless military machines ever assembled, instruments of conquest in the hands of fascist maniacs.” Many American historians are convinced that the men and women who fought in WWII were in fact a remarkable generation “because they succeeded on every front. They won the war; they saved the world.”

My dad, a veteran and lifetime resident of San Antonio’s Westside, seldom mentioned his World War II service to his country, and never thought of himself as belonging to America’s “Greatest Generation.”

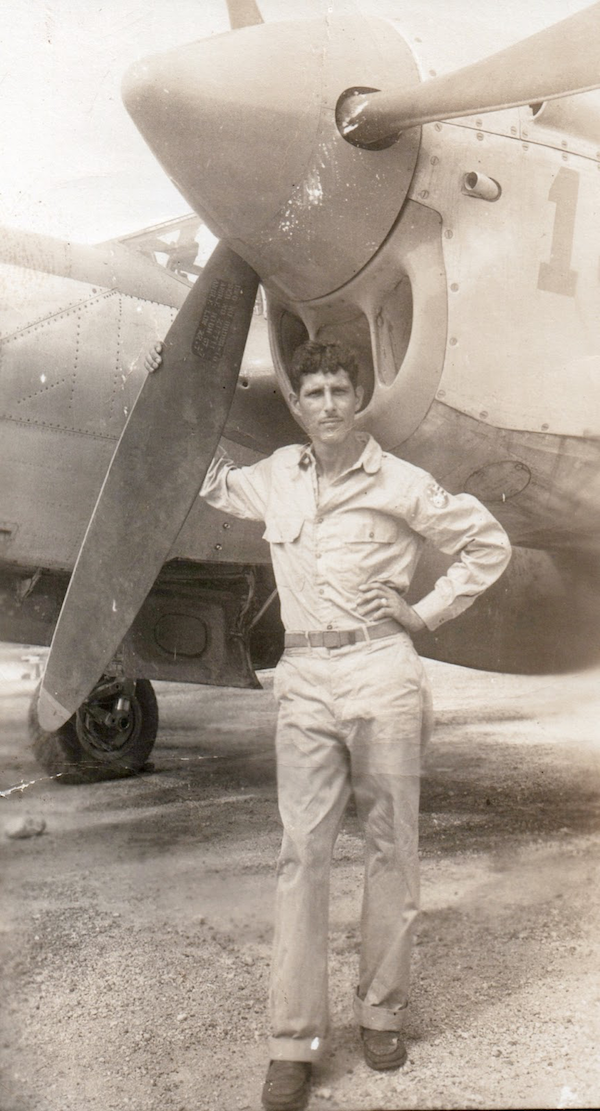

Dad volunteered for the Army Air Corps shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He saved the documents showing that he officially joined the Air Corps, a precursor to the U.S. Air Force, on October 23, 1942. A year earlier, at age 23, married and the father of one son, dad graduated from high school. He dropped out of Lanier High School at age 15 and returned to high school classes in his early twenties to finish his education at the San Antonio Technical and Industrial night school program. He studied radio repair and upon enlisting in the military, he was assigned to the United States Army Air Corps radio repair training program. A photo he saved may have been taken on the steps of his old high school showing the group of new recruits.

Henry Romo, with a friend on the remains of a downed Japanese airplane.

My dad and my mom, Alicia, along with their newborn son Henry Jr., were sent to Austin in early 1943. My dad was to continue his radio repair course. Over the next six months dad took classes taught in a University of Texas barracks loaned to the U.S. military. Dad became highly proficient in repairing radios and hoped that his radio skills would enable him to fly with the bomber squads as a radio technician.

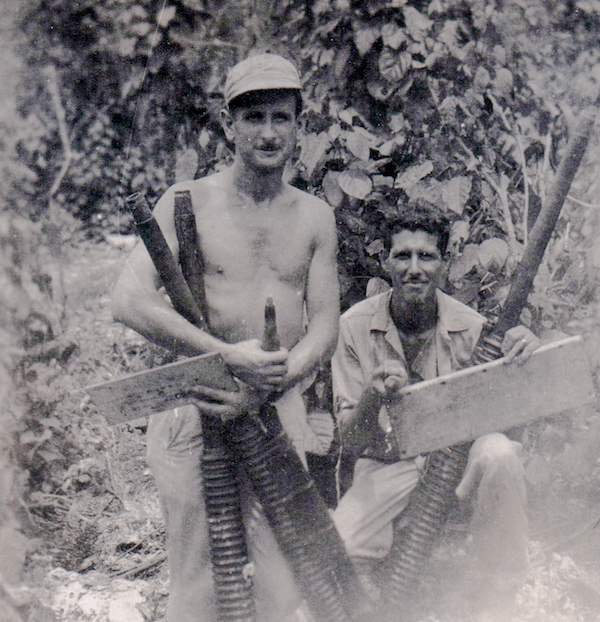

He never got to fly with the bomber squads. He was fortunate because the vast majority of the bombers that flew out of the Phillipines never returned to base. I once heard him remind a war buddy who served with him in the same squadron that after the company’s cook [Pfc. Miles H. Clayton] was killed in a bombing raid, my dad was assigned to help out in the base kitchen. Dad was modest and laughed the episode off. In reality, the photos he saved show that he was also engaged in field battles in the Philippine jungles.

Henry Romo and buddy in combat.

Dad spent some time in New Guinea, but he was deployed the last two years of the war to the Island of Leyte, a major island of the Philippines. Scholars have declared the Battle of Leyte as the last major battle of the Pacific. The defeat of the Japanese forces at Leyte demonstrated the U.S. superior forces and weapons. Brig. General J.V. Crabb, Commander of the 5th Bomber Command, distributed a booklet to all the men who served with him. The booklet, designed and published at the base, included photos, drawings, and written accounts of some of the battles described by members of my dad’s squadron. Several of the photos and stories give observers a close-up look at how the U.S. military fought.

Henry Romo and friend on a captured Japanese tank.

Brokaw’s interest lay in writing about the men and women at war as well as what their lives were like when they returned home at the end of the war. Henry Romo came home from the war to find that discrimination against Latinos had not abated during his time away. After a Latino family learned that the local funeral home in Three Rivers, Texas would not handle the burial of Pvt. Felix Longoria—because the local white community might object—my dad joined Dr. Hector Garcia in a newly formed Latino organization, the American G.I. Forum. The Forum successfully gained the support of the newly elected U.S. Senator Lyndon B. Johnson, who arranged for Pvt. Longoria, who had been killed in the Philippines, to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery outside Washington, D.C.. My dad remained active with the G.I. Forum for many years, serving on the National Board and as director of the San Antonio regional chapter.

Henry Romo, in Leyte Island. 5th Bomber Squad. Photo found in the 1990s by Henry Romo, Jr.

My dad was proud of serving his country. He was not unusual as a veteran in not talking about his war experience, especially to his family. He never discussed his military service at any family gathering. The one time we heard about his WWII experience was when a former military buddy dropped by to visit with him at his small grocery store in the Westside of San Antonio. On Veterans Day, I am happy to share some of the WWII photos that my dad treasured but never discussed with his family.