Teach the History Behind "Emancipation" with the Primary Sources

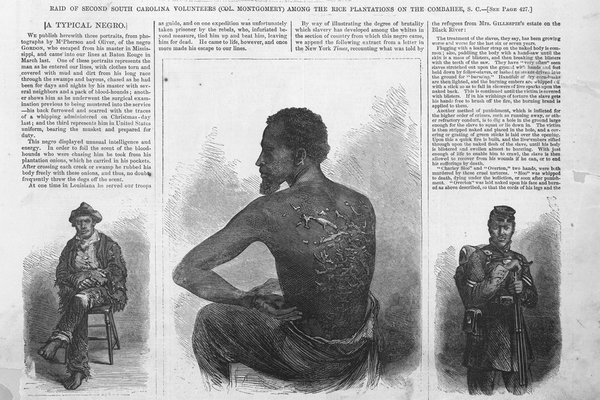

From Harper's Weekly, July 4, 1863. At center is a reproduction of Mathew Brady's famous 1863 photograph of Peter's scars.

Emancipation, directed by Antoine Fuqua and starring Will Smith, is loosely based on the life of an escaped slave in Louisiana, known in contemporary accounts as both Gordon and Peter, who fought in the Union Army helping to defeat the Confederacy and end slavery in the United States. Gordon/Peter is best known for an early photograph of keloid scarring on his back that was used by abolitionists to show the inhuman nature of enslavement. I found the movie dark and difficult to watch, both because it was filmed in black and white and because of its focus on the horrors of slavery and the Civil War. Slavecatchers killed and beheaded runaways; in Union camps surgeons amputated limbs from the wounded and deposited them in piles to be carted away; reconstructed battlefields were filmed covered with dead bodies. As a teacher, my preferred movies on slavery and African American participation in the Civil War remain Gordon Parks’ Solomon Northup’s Odyssey (1984) and Edward Zwick’s Glory (1989). Both films did a better job with character development, and the Parks’ film did a much better job portraying slavery as a work system and showed African American community and humanity under the direst circumstances. They provide more useful segments that can be played and discussed in classes.

The best thing about Fuqua‘s Emancipation was its rediscovery of the life of Gordon/Peter, whose image has survived because of the well-known photograph but whose personal and heroic story was largely forgotten. Fortunately, there are at least three accessible contemporary reports that provide documentary coverage of his life and the battle of Port Hudson that can be used in history classes: a Harper’s Weekly account from July 4, 1863 (429-430), a letter to the editor of the N.Y. Tribune dated November 12, 1863, and a New York Times article from June 14, 1863 that details the brutal treatment of enslaved Africans on Louisiana cotton and sugar plantations. The Harper’s Weekly report included three photographs, “Gordon as he Entered Our Lines” barefoot and dressed in rags; Gordon Under Medical Inspection” showing the keloid scarring, and “Gordon in his Uniform as a U. S. Soldier.” In the movie, director Antoine Fuqua did a good job of building on these sources, although the parts about Peter’s family, the way he was ripped away from them and their eventual reunification are fictional.

The Harper’s Weekly article was titled “A TYPICAL NEGRO.”

“WE publish herewith three portraits, from photographs by McPherson and Oliver, of the negro GORDON, who escaped from his master in Mississippi, and came into our lines at Baton Rouge in March last. One of these portraits represents the man as he entered our lines, with clothes torn and covered with mud and dirt from his long race through the swamps and bayous, chased as he had been for days and nights by his master with several neighbors and a pack of blood-hounds; another shows him as he underwent the surgical examination previous to being mustered into the service —his back furrowed and scarred with the traces of a whipping administered on Christmas-day last; and the third represents him in United States uniform, bearing the musket and prepared for duty.”

Harper’s Weekly credited Gordon with “unusual intelligence and energy” and described how he was able to “foil the scent of the blood-hounds who were chasing him” by rubbing “his body freely with these onions, and thus, no doubt, frequently threw the dogs off the scent.” According to the Harper’s Weekly story, Gordon initially acted as a guide for federal troops during the Louisiana campaign and was captured by Confederate forces and nearly killed. Left for dead, he managed to escape back to Union lines and entered the 1st Louisiana Native Guard, also known as the Corps d’Afrique. I believe the Corps d’Afrique was unique among African American units during the Civil War because its officers up to the rank of Captain were Black.

The New York Tribune published an extended letter signed by “Bostonian” and dated November 12, 1863. The letter claimed to correct misstatements in the Harper’s Weekly article and to

contradict the malicious falsehoods that have appeared in the Rebel organs of the North. No sooner had this heart-striking picture begun to circulate, and awaken a thrill of horror among the loyal and humane portion of the community, then the Copperhead press at once spit forth their poisonous venom, and boldly asserted that the whole story was a fabrication from beginning to end—the fruitful results of a fanatical Abolitionist’s deluded imagination.

In response,

the friends of freedom in New York and Boston have purchased "carte de visite" size photograph copies of the abused negro, as a faithful picture of the realities of Slavery as it exists in the southern States.

A “carte de visite” photograph was approximately 2 by 3.5 inches, about the size of a business card today.

In the letter, "Bostonian" claimed to have brought the original photographs to Harper’s Weekly after a March visit to Louisiana and he vouched for their “entire accuracy, as well for the truthfulness of the brief account of the outrages perpetrated upon the unoffending negroes which was published in connection with the pictures.”

In a correction to the Harper’s Weekly article, Bostonian explained that the three photographs published by the journal actually showed two different people. The person dressed in rags was a man named Gordon who was part of the group that escaped through the swamps together. The person with the lacerated back’s name was Peter. Peter barely spoke English because French was the language of the Louisiana planters and the people they held in bondage. When military officials interviewed him, Peter reported his “master’s name is Captain John Lyon, cotton planter, on Atchafalaya River, near Washington, La” and that the scars were the result of a whipping “two months before Christmas.”

Bostonian ended the letter praising the men who

chased by "hunters" with their savage pack of hounds, but they were ingenious enough to wade and swim through every stream they could find on their way, twice swimming the turbid waters of the Amite River in their wanderings. Upon coming from the water, they had presence of mind and sagacity enough to rub every portion of their body with onions and strong-scented weeds, in order to elude the trail of the bloodhounds, who were several times close upon them. To their intelligence may be attributed their narrow and fortunate escape from the terrible fate that befell “Poor John” their companion.

On June 14, 1863, The New York Times, ran a front page article headlined “FROM THE MOUTH OF RED RIVER.; Gunboat and Army Movements on the Mississippi. Gen. Banks’ Investment of Port Hudson. IMPORTANT SUBSEQUENT EVENTS.” The article recounted

Several parties of colored people have come down in canoes and flats -- having escaped on Monday and Tuesday last. They represent that the blacks are subjected to the greatest brutality by the enraged rebels, who find no other objects on whom to vent their chivalric spite. They run them down with horses; shoot them on the road, or tie and drag them with ropes at the tail of their horses toward the jail, which is now crowded so full that they cannot get any more inside the walls. All, white or black, who have shown any favor or countenance to the invading Yankees, have been arrested for punishment. Several are known to have been shot.”

Refugees reaching Union lines were interviewed about the conditions they were fleeing, and the bulk of the article reported on the treatment of enslaved Africans on Louisiana plantations. At least one planter threatened enslaved Africans that if they escaped to the Union lines "They would be sold to Cuba; be worked to death, or turned out to starve."