Learning from Historical Fiction: A Family Tale Reveals a Brief Multicultural Moment of the American West

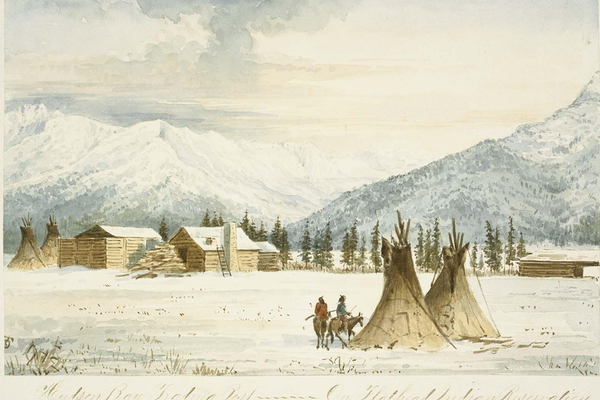

A watercolor depicts the Montana fort of Angus McDonald, the last Hudson's Bay Co. trader in the United States

Historians may well wonder what drives a creative writer to plunge into a previously unknown period to produce that peculiar hybrid: the “historical novel.” We historical novelists often ask ourselves the same question—usually right as we start trying to wrestle masses of factual detail into story form. Every project appeals for different reasons. Yet I have found the same thing happening in each dive into a new historical period. Whether the subject is the power politics of the medieval church, postwar Germany or the colonizing of the American West, the act of researching and writing a historical novel is a crash course in a portion of the past that helps me—and with luck my readers—gain new perspectives on the world.

My latest novel, The Shining Mountains, the story of a Scots-Nez Perce family caught in the crossfire of Western expansion, was particularly rich in this regard. The novel’s themes could not be more pertinent: Americans today are acutely conscious both of how history is told and of hearing voices from cultures long marginalized. The novel is a tale of the multicultural world that existed before American settlement of the West which includes indigenous points of view.

Yet this broader context was far from my mind at the start. I simply wanted to write a novel about the amazing life of my ancestor’s brother Angus McDonald, the last trader for the Hudson’s Bay Company in the United States, and his Nez Perce wife Catherine Baptiste, along with the family they raised at a time of tremendous conflict and change.

Instead, over the four years it took to research and write, I wound up teaching myself the basic facts of Native history in this country, with a focus on one specific slice: between 1842 and 1879 in the Pacific and Rocky Mountain Northwest. Then, using fiction—the imagined story of two real individuals—I was able to investigate and ultimately portray historical events that most of us never learned in school.

Every story is about not just characters, but the world these characters inhabit. Learning everything I needed to describe this world accurately was a tall order, but one I approached with energy and fascination. This was my family’s history, after all; this is America’s history as a nation. I had to educate myself on the fur trade period and the role of America’s political, military, religious and civilian actors as the doctrine of Manifest Destiny unfurled. At the same time, I had to discover everything I could about the real protagonists' lives, in order to present a story at the level of granular detail that fiction requires.

Angus McDonald and his family were sufficiently prominent to have left letters and documents in university archives. I sought and gained the support of his descendants and the tribes involved, and started digging. It should go without saying that I, like every writer of historical fiction, am dependent upon—and exceedingly grateful for—detailed and labor-intensive studies of primary sources by professional historians. We could not spin our fictions without them. Subject headings in my archive suggest the scope of my initial research: fur trade; Hudson’s Bay Company; company marriages; Glencoe massacre; Nez Perce War; Salish culture; buffalo hunting; Yellowstone Park. Then the events in which the McDonalds were involved demanded that I learn even more: Steptoe Massacre; Yakama war; Isaac Stevens’ transcontinental railroad survey; 1850s treaty negotiations; Idaho and Washington gold rushes; clippings from territorial newspapers. The great historians of this time and place—Alvin M. Josephy Jr., Jerome A. Green, Allen P. Slickpoo, Lucullus McWhorter—are the authorities on which I built my part-real, part-imagined world.

There is lively debate today about how “true” historical fictions should be. I tend to agree with those who criticize events and situations invented from whole cloth. The truth is dramatic enough, more often than not. I have also worked as a journalist committed to accuracy in my reporting for the past forty years. So I bring the same focus on getting the facts right to my fictions. This has been especially true of the history behind The Shining Mountains.

Over time I have come to see that the truths on which this book rests matter as much to me as this one family’s story. The more I learned, the more I grasped that I might have a deeper purpose in telling their history. I finally concluded that I wanted readers to experience what I had experienced, viscerally, step by step: to see exactly how the U.S. government and the settlers it encouraged actually dispossessed these Native tribes. And I wanted them to learn—as I so belatedly had—that for decades before these wars and massacres that “cleared” the country for pioneers, a vibrant multicultural society existed in the Pacific and Rocky Mountain Northwest. To that end, I included an appendix in which readers could fact-check which parts of the story were true and which invented.

I once attended a conference in which an eminent historian of Tudor England praised the late great Hilary Mantel for her brilliant grasp of the entire period. In recent years the profession seems to have tempered its reflexive rejection of fictional forays into its territory. Many historians, after all, now write fictions set in their periods of expertise. It is well established that in the classroom, at least, history told in story form lodges more firmly than factual data in students’ minds. Of course, older readers vary greatly in the approaches they enjoy. Some want to learn, others just to be entertained.

In the same way, I suspect, some writers of historical fiction aim to educate, while others are more drawn to portraying universal human drives. Looking back, I see that I did the latter in my first novel, Gutenberg’s Apprentice, a tale of vast technological change. In The Shining Mountains, I come down more on the educating side. The reason for this difference, I think, is the position in which I find myself: a writer from the dominant culture writing about a largely erased minority group. I wanted to use my bullhorn, and my privileged standing, to teach a largely white readership about these historic wrongs.