“Of the East India Breed …”: The First South Asians in British North America

An entry in a 1635 Virginia land record is the earliest indication of the presence of a South Asian in colonial North America. “Tony East Indian” -- with a diminutive first name and no last name except for an epithet indicating a vague understanding of geographical origin and racial identity, “Tony” is an insignificant speck in the vast landscape of the emerging colony. But his presence is surely remarkable – this man who came from the very antipodes, as it were, in an era when even the voyage from Europe to the New World was lengthy and dangerous.

The person who listed Tony and 23 other men as headright to the 1200 acres of land he was registering was George Menefie, a prominent Virginia merchant, landowner, and colonial office holder who had himself arrived from England in 1623. Tony’s transport to Virginia might have been arranged by Mr. Menefie or an agent acting on Menefie’s behalf, but his journey most certainly involved forces of even greater magnitude than a single Virginia landholder.

In 1600, when Queen Elizabeth I had granted a charter to the “Company of Merchant of London trading into the East indies …,” the members of the East India Company, as it came to be known, had already recognized the tremendous profits to be made from trade with the enormous cluster of kingdoms and principalities known as “India.” Always a land of myth and marvel in the western imaginary, India, was, by the early 1600s, a still wondrous but also geographically precise space reached by navigable sea routes. The East India Company went on to become a behemoth of a corporation-cum-government, but even in its relatively modest early years, some Company officials returning to England took back with them (perhaps, in some cases, forcibly) Indian servants, many of whom continued to live and work in London. Adding to the East Indian population in England were other “lascars” or sailors employed in Company ships sailing to England who found themselves stranded and destitute in and around English ports. England, one can assume, was the mid-point of Tony’s journey to Virginia.

Although Tony and the other East Indians (as they were called) who followed him to colonial America are almost erased from our collective memory, the fact of their presence provokes some interesting questions and offers up some important reminders.

First, were they brought over as servants? This is a distinct possibility. After all, increasing numbers of people came to Virginia after 1620 as indentured servants, helping swell the labor force needed by the colonial setters. As John Pory, speaker of Virginia’s first general assembly famously wrote: “Our principal wealth … consisteth in servants.” Deeds of indenture were drawn up prior to travel, though some agreements, especially in the early years, were negotiated with employers after landing. In both cases, there were varying degrees of exploitation and abuse and deeds of indenture of all servants, East Indians possibly among them, could be sold, bought, and transferred.

On the other hand, was Tony enslaved? Or, to put it differently, did he (and the other East Indians who followed him) have the same rights and freedoms as indentured white servants or did they suffer the same restrictions as enslaved African people? The exact standing of early Africans in Virginia and elsewhere is debated by historians, but one can perhaps agree that a few notable Black landowners notwithstanding, most Africans (even those who were servants rather than enslaved) probably did not share the same status as white migrants, even white servants. Slavery probably existed in fact even before it became institutionalized. Richard B. Allen, who has studied the East India Company’s (and other European) involvement in the slave trade in the Indian Ocean, has made the argument that the trans-Atlantic slave trade was not distinct from the concurrent Indian Ocean traffic in humans. While the latter mainly involved the sale of East Africans and natives of Madagascar, a number of enslaved Indian people were taken from the port cities of South India and the coastal regions of Bengal.

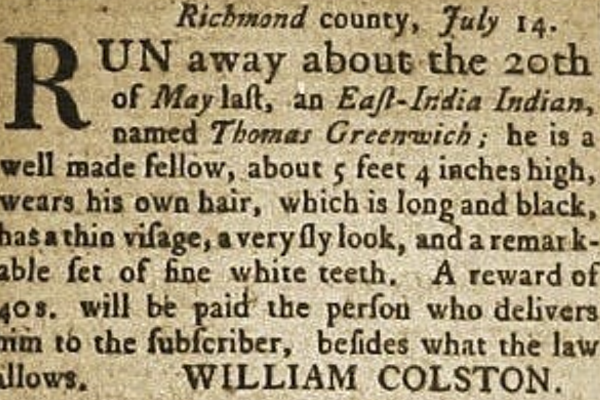

Some records also indicate that Indians were enslaved to English masters in their voyages across the Indian Ocean. No certain claim can be made about Tony’s status in Virginia, but some 70-odd years later, in 1708, one Thomas Mayhew (who might have also gone as Thomas India) stated in his petition for freedom that he was born in India, taken to England where he was baptized, and subsequently transported to Maryland with his mother. Although he claims that he came as an indentured servant, his mistress, he states, kept him as a slave. Similarly, a 1786 advertisement for a runaway “an East India negro man” named Jean describes him as “slave born” although “he will call himself free,” while one Pompey is described in a c. 1735 court order from Spotsylvania County as “an East Indian (slave) belonging to William Woodford, Gent.”

Image Geography of Slavery in Virginia, Virginia Center for Digital History. Advertisement from Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg), August 4, 1768

The limited evidence available also, however, indicates that, as slavery became increasingly institutionalized and racialized in British America and subsequently in the fledgling United States, at least some East Indians were successful in their petitions for freedom because they were East Indian (presumably rather than African). So, in 1777, Peter Charles “is an East India Indian and justly Intitled to his freedom”; one Will, who was “fraudulently trapped out of his Native Country in the East indies and thence transported to England and soon after brought to this Country and sold as a slave …,” was awarded freedom in 1708 as the Court considered that “the sd. Will ought to not have been sold as a slave and that he was a freeman …”

A third possibility is that many East Indians (like those Africans who were designated indentured servants) were less likely to have held well drawn-out deeds of indenture, so resulting in increased exploitation, which might have taken the form of very long (perhaps even lifelong) terms of servitude.

Numerous East Indians subsequent to Tony are mentioned in deeds, estate accounts, runaway ads, and court documents. They have been enumerated and listed by Paul Heinigg in his Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia and South Carolina and the information further compiled by Francis C. Assisi and Elizabeth Pothen in “South Asians in Colonial America” among others. One finds them (mostly men, but some women as well) mentioned in 18th century court judgments as having completed their indentures, in inventories of personal property, in advertisements for runaways (although at least one East Indian was apparently not above reporting a runaway himself). Some East Indians also fought in the Revolutionary War, both on the American and the British side.

Both English and American records indicate that the terms “East India Indians, “Asiatic Indians,” “blackmoors,” “(East India) moors,” and “(East India) negroes” were used to describe this population. Sam Locker, a runaway, is described as a “negro man … has rather long hair being of the East India breed” while another runaway, John Newton, is described as “an Asiatic Indian” in one edition of the Virginia Gazette but as a “mulatto” in another, while, as late as 1794, 16-year-old Crispin, a runaway from Philadelphia is described as “a kind of mulatto East India boy.” In some cases, a distinction is more clearly drawn between East Indians and people of African descent. One Ann James, presumably a white female, named the father of her child as Pompey “an East Indian,” and was judged by the court as not carrying a “mullato child” as the law “only relates to Negroes and Mullatoes and being Silent as to Indians.…” One can conclude that from the earliest date this group of arrivals exemplified the complexity of race and race relations in colonial America.

Early East Indians soon blended with the African population, so providing among the first examples of alliances between peoples of color. They created “multi-ethnic” families and, consequently, further confounded the already complicated and shifting idea of race. Will, a man who ran away from Mr. Hepburn’s Plantation in 1760 in Frederick County, Maryland is described as being “of a yellow complexion, being of a mix’d Breed, between an East Indian and a Negro.…” Thomas Mayhew, who escaped from a Maryland jail in 1760, is described as being “of a very dark Complexion, his Father being an East India Indian.…” The wording of the latter notice indicates that Thomas might have been the product of a union between a white woman and an East Indian man.

Tony’s story—and that of other early East Indians—is a significant preface to the narrative of South Asian immigration to the USA although, after their merger with the African-American population, they no longer retained their “East Indian” identity. Further, their presence is a symptom and consequence of elaborate and far-reaching circuits of global movement and exchange, which lead to new understandings of self and other and new experiences of both familiarity and xenophobia. More specifically, they are a reminder that, while the variegated and complex story of early America is certainly a result of cross-Atlantic movements, it is also shaped by proto-imperial networks that traversed the entire globe.

Most notably, these East Indians are a reminder that the “Atlantic world system” was also connected to the societies and peoples of the Indian Ocean. In fact, the small group of merchants who formed the East India Company also had interests in the Virginia Company (apart from sharing the same London offices and having the same governor for a while). It is not too surprising, then, that servants who might have been brought to England by EIC officials eventually accompanied their masters, or were sent by them to America. The East Indian presence in North America is only one sign of this confluence and interconnectedness between India and America: Europeans paid for Indian commodities with silver bullion from the Americas and for African slaves with Indian textiles; later, Lord Cornwallis, after his 1781 defeat in Yorktown, went on to serve as Governor-General of India. Also of interest is the fact that Elihu Yale, major donor to the institution that became “Yale College” had been Governor of Madras in India and made much of his fortune in that country.

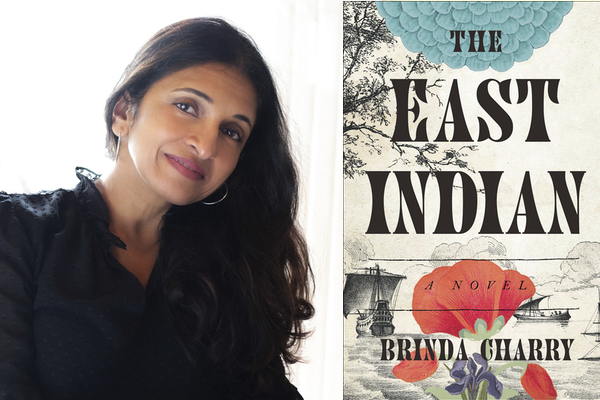

The English poet John Donne in a characteristic rhetorical flourish sees his beloved as the confluence of the two hemispheres. Both the Indias of spice and mine … lie here with me, he proclaims in his 1633 poem “The Sunne Rising” – a line surely inspired by the new geographies and the interconnected new world (both brave and brutal) coming into being. That is what moved me, too, when I imagined the long-forgotten Tony’s story in my forthcoming novel The East Indian: unlikely paths that crossed and collided, a voyage that is somehow both fantastical and plausible, and the sheer length of the road traveled … indeed, such a long journey….