Why is the American Right so Thirsty for Generalissimo Franco?

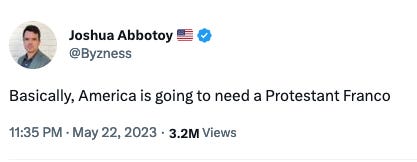

Joshua Abbotoy, a private equity lawyer who is currently a Lincoln Fellow at the far-right Claremont Institute, recently tweeted:

Francisco Franco, of course, was a brutal fascist dictator who launched a failed coup against Spain’s democratically elected left-wing government in July 1936. He then fought a bloody and ultimately successful war to overthrow that government with the assistance of Mussolini and Hitler, and was responsible for murdering hundreds of thousands of Spanish civilians during and after the war. Unlike Hitler or Mussolini, however, Franco successfully manufactured a portrait of himself as a fearless defender of Catholicism in particular—and Western Christendom in general—against the depraved excesses of communism.

Admiration for the generalissimo is not new on the U.S. right. After World War II, Franco was lauded by American conservatives for being the sole national leader to have defeated Communism in an armed struggle. (Though not communist itself, Spain’s republican government received military aid from the Soviet Union.) Pilgrimages to Spain became de rigueur among conservative American Catholics in the 1950s and 1960s. The godfather of modern U.S. conservatism, William F. Buckley, Jr., visited Spain in 1957 and lauded Franco for “wrest[ing] Spain from the hands of the visionaries, ideologues, Marxists, and nihilists.” Buckley’s brother-in-law Brent Bozell briefly moved to Spain in the 1960s.

Nor is Abbotoy is alone in his lust for authoritarianism today. Harvard law professor Adrian Vermeule—himself an admirer of the Franco regime—raised eyebrows last week when he declared that “the only power that can make corporate entities feel the sting of political enmity is state power.” What got Vermeule so worked up? The Los Angeles Dodgers had invited the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a satirical drag group, to its Pride Night. Under pressure from right-wing Catholic groups, the Dodgers revoked the invitation. But facing a backlash to the backlash from LGBTQ+ organizations, the baseball club reversed course.

For those with a sense of perspective and/or lack of a burning hatred in their hearts, the Dodgers episode underlined the pettiness and stupidity of the drag show moral panic, as well as the fickleness of corporate attitudes toward LGBTQ rights. But for far rightists like Vermeule, the episode underlined that, given the public’s increasing empathy with formerly marginalized groups, the political tactics of organized pressure, lobbying, and boycotts are a losing proposition for the right. In their minds, only state power will do—and, as perceptive analyses of Vermeule’s position have pointed out, his legal and political philosophy draws explicitly from the Francoist tradition.

Vermeule is a devout Catholic, as were Buckley and Bozell. Abbotoy’s call for a Protestant Franco is superficially more perplexing—especially in light of right-wing Catholicism’s contempt for Protestantism as the fountainhead for liberalism in all of its detestable glory. But it makes more sense in the context of the sort of “national conservatism” that is making the transatlantic circuit these days. Unlike Spain, a country historically dominated by the Catholic Church, America has a historically Protestant identity. Hence, the kind of fascistic American strongman craved by Abbotoy must correspond to this basic rule of American identity.