The Unlikely Success of James Garfield in an Age of Division

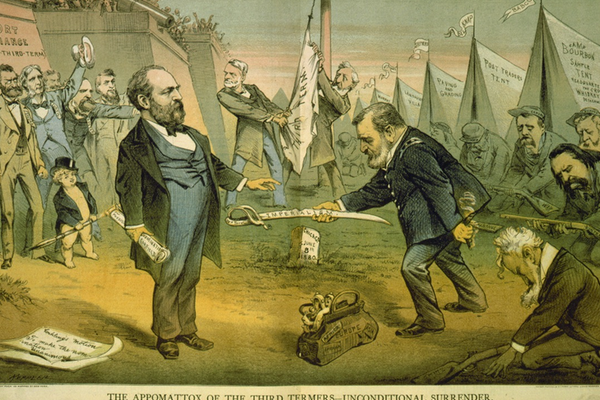

An 1880 Puck Cartoon depicts Ulysses Grant surrendering his sword to James Garfield after being defeated for the Republican nomination.

The candidate, at first glance, seemed to have no business being his party’s nominee for the White House. In an era seething with political strife, he had long been viewed by peers in Washington as a pleasant but out-of-touch figure. Partisan warfare was not his strong suit; he cultivated friendships with civil rights opponents and election deniers alike. He enjoyed scrappy political debate but refused to aim any blows below the belt (“I never feel that to slap a man in the face is any real gain to the truth.”) What’s more, American voters seemed to be in a decisively anti-establishment mood, and this nominee had been a presence in Washington for almost two decades – the epitome of a swamp creature.

Yet, somehow, it added up to a winning formula: James Garfield, the nicest man remaining in a polarized Washington, would be elected America’s next president in 1880. His rise to power would be framed as a rare triumph of decency in the increasingly bitter political environment of late 19th century America. It has resonance today as our country again navigates similar public conditions.

Garfield’s election was the very first of the Gilded Age. It was a time defined by tremendous disparity emerging in America. Men like Andrew Carnegie and Jay Gould were ascendant members of a new ruling class of industrialists, the so-called “robber barons.” But their factories were grinding down the working class; America’s first nationwide strike had broken out in 1877. Meanwhile, Reconstruction had failed in the South, leaving Black Americans in a perilous spot. They technically possessed rights, but, in practice, had lost most of them after former Confederates returned to power and reversed the policies of Reconstruction.

Yet the period’s discord was most obvious in its politics. The last presidential election had produced what half of Americans considered an illegitimate result: poor Rutherford Hayes had to put up with being called “Rutherfraud” for his term in the White House. Meanwhile, the broader Republican Party had fractured into two vividly-named blocs (the “Stalwarts” and the “Half-Breeds”), each of which loathed Hayes almost as much as they did each another.

In this setting, Minority Leader James Garfield was a uniquely conciliatory figure – the lone Republican who could get along with all the fractious, squabbling members of his party. Stalwarts described him as “a most attractive man to meet,” while the leader of the Half-Breeds was, perhaps, Garfield’s best friend in Congress. President Hayes also considered Garfield a trustworthy legislative lieutenant. The overall picture was a distinctly muddled approach to factional politics: Garfield did not fall into any of his party’s camps but was still treated as a valued partner by each.

Much of this came naturally (“I am a poor hater,” Garfield was fond of saying). But there was also, inevitably, political calculus informing it – the kind that comes from decades spent in Washington, trying in vain to solve the nation’s most pressing issues.

Exceptional as Garfield’s political style was, his life story was more so. He had been born in poverty on the Ohio frontier in 1831 and raised by a single mother. A dizzying ascent followed: by his late twenties, James Garfield was a college president, preacher, and state senator; only a few years later, he had become not just the youngest brigadier general fighting in the Union Army, but also the youngest Congressman in the country by 1864.

His talent seemed limitless; his politics, uncompromising. The young Garfield was an ardent Radical Republican – a member of the most progressive wing of his party on civil rights and the need for an aggressive Reconstruction policy in the postwar South. “So long as I have a voice in public affairs,” Garfield vowed during this time, “it shall not be silent until every leading traitor is completely shut out of all participation of in the management of the Republic.”

But he lived to see this pledge go unfulfilled. Garfield’s Congressional career was exceptionally long – stretching from the Civil War through Reconstruction and beyond – and his politics softened as events unfolded. Principle yielded to pragmatism during what felt like countless national crises. “I am trying to be a radical, and not a fool,” Garfield wrote during President Johnson’s impeachment trial. By the end of 1876, a young firebrand of American politics had evolved into a mature legislative chieftain – the Minority Leader of a fractious Republican Party. Younger ideologues of the Party had Garfield’s sympathy but not his support. “It is the business of statesmanship to wield the political forces so as not to destroy the end to be gained,” he would lecture them.

It is no wonder, then, that Garfield’s reputation as an agreeable Republican was not entirely a positive one. From Frederick Douglass to Ulysses Grant, friends tended to say the same thing: that Garfield’s flip-flopping and politeness indicated he “lacked moral backbone.” Garfield, in contrast, would argue that open-mindedness was a sign of inner strength rather than weakness.

This argument was put to the test in the election of 1880. Republicans entered their nominating convention with a handful of declared candidates who had no clear path to a majority of party support. They emerged behind a surprising choice – James Garfield, who had been picked (apparently against his will) off the convention floor as a compromise candidate. The rank-and-file rejoiced. “His nomination will produce perfect unison,” one celebrated, “because he has helped everybody when asked, and antagonized none.” Garfield was not so exuberant about the outcome. Over the course of his political career, he had learned to view the presidency with deep suspicion; none of the Administrations he had witnessed up-close ended well.

His reservations were well-placed. While trying to appease his party’s different blocs, President Garfield ultimately failed to keep the peace between them – kick-starting a chain of events that led to his murder. The result, ironically, was the nation’s politics suddenly shifted to resemble his own. Americans made Garfield into a martyr and blamed the hyperpartisan political climate of the country for his death. A great period of correction began, but, in all the drama around Garfield’s assassination, his remarkable life was overshadowed by its own untimely end.

On his deathbed, President Garfield seemed to sense this would be the case. Turning to a friend, he asked if his name would “have a place in human history.” The friend’s affirmative answer appeared to relax him. “My work is done.”