Has Labour Let Down British Voters?

Labour Party (UK) leadership election - Wikipedia

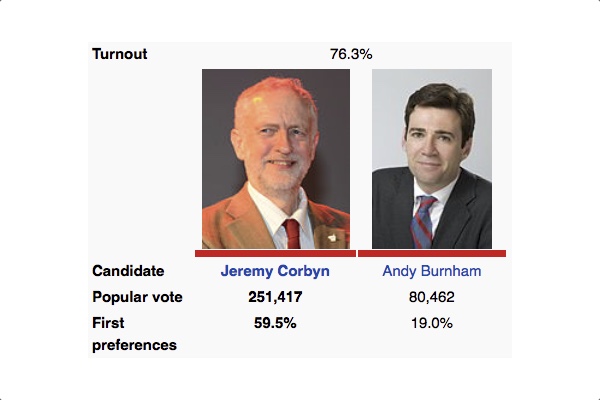

It’s over. The ballots have been tallied and Jeremy Corbyn has been elected leader of the British Labour Party. The uncomfortable task of rebuilding following defeat in the 2015 general election falls to an obscure backbench MP who has never held a ministerial position and who defied the party whip on over 500 occasions.

It wasn’t meant to be this way. Party leaders expected to unify around a centrist or right-leaning candidate. This would lance the public perception that the Labour Party had turned too far to the left under Ed Miliband and could not be trusted to run the economy. Instead, the party has selected a candidate who is unlikely to win a general election.

So what does Corbyn plan to do? Suggested domestic policies include the renationalization of the railways and energy companies, the abolition of university tuition, investment in public housing, the imposition of rent controls, the creation of a national education service, and the prevention of private sector involvement in the NHS. Corbyn has proposed ending corporate tax relief and financing a national investment bank with the proceeds and using quantitative easing to fund public services.

His international policies are a mixed bag. Corbyn plans to withdraw Britain from NATO, opposes Britain’s nuclear deterrent, Trident, and has vowed to end overseas military intervention. He has expressed skepticism over British membership in the European Union, arguing that the EU uncritically reflects neo-liberal assumptions. He has proposed closer ties with Russia. In a moment of striking naiveté, Corbyn described the death of Osama bin Laden as a tragedy. More worryingly, while there is no suggestion that Corbyn is anti-Semitic or anti-Israeli, on several occasions he has shared platforms with figures who espouse both views, as well as with Holocaust deniers.

Individually, some of Corbyn’s policies seem sensible. Leading economists welcome the idea of a national investment bank and the ending of disastrous Conservative austerity policies. Collectively, they prove problematic. Conservatives and right-leaning publications have derided Corbyn for returning to the statist tax and spend policies that voters rejected in 1979, 1983, 1987, and 1992. The left is equally concerned. Former Labour prime ministers Tony Blair (1997-2007), and Gordon Brown (2007-2010), have expressed concern about the return of ideas that made Labour unelectable for two decades. So too have major left-leaning publications such as the Guardian, New Statesman, Independent, and the Daily Mirror.

Corbyn’s candidacy has been driven by a desire to disassociate the Labour Party from Tony Blair. Despite winning three elections in a row, Blair is reviled today. This is for two reasons: the Iraq war and the 2008 global financial crisis. Blair used a “dodgy dossier” of outlandish claims about Iraq’s military capability to convince the public of the need for war. Between 1997 and 2010, Labour economic policies promoted free trade, extensive international investment in Britain, and light regulation of banks and the City of London. Some supporters believe these worsened the effects of the 2008 global financial crisis in Britain.

Forgotten are the positives of the Blair years. After becoming leader in 1994, Blair swiftly modernized the Labour Party. He embraced Third Way thinking, which used the proceeds of free market policies to fund social justice programs. The results proved startling. Between 1997 and 2007, GDP grew by 2.89 % a year, the highest rate by far amongst the major European economies. This unprecedented prosperity financed investments in public infrastructure. London School of Economics research illustrates how Labour revitalized social services that had been neglected for decades. Thousands of new teachers, doctors, and nurses were employed and hundreds of schools and hospitals built. Funding for the National Health Service increased. Access to social services, health education, and childcare was expanded for minorities and people living in impoverished inner cities and remote rural areas. A minimum wage was established and extensive retraining offered to the long-term unemployed. A system of tax credits and indirect taxes on consumption redistributed wealth without raising income tax rates.

So where can Labour go from here? Corbyn’s leadership looks troubled already. His supporters waged a successful insurgency campaign that bypassed the institutional structures of the Labour Party. The nature of this victory will make it difficult to gain support. Corbyn won a majority of party members, but received the votes of just 20 of 230 MPs. Senior MPs have refused to serve in Corbyn’s shadow cabinet. Centrist and right-leaning MPs plan to form intra-party organizations to counteract Corbynite policies. Leading union officials have demanded that opponents of Corbyn accept the new leader or leave the party. Overshadowing all of this is the question of how a serial rebel can demand loyalty and discipline.

Corbyn is making a bet that principles matter. Yet what use are principles if they cannot win? Corbyn is not just Labour leader, but Leader of the Opposition. His job is to develop policies that will pressure the current Conservative administration and present Labour as an alternative government. How though? Fairly or unfairly, Corbyn has been deemed to sit outside of the pragmatic center of British politics. History shows the consequence of this course of action. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, Labour pursued the same policies that had led to economic crisis a decade earlier. The result was defeat after defeat. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the Conservatives grew convinced that what the public really wanted were harsh free market policies, severe cuts in spending, and lengthy debates about the EU. In three elections, they were handily trounced by Labour. Blair understood keenly that the alignment of principles with the pragmatic center of British politics was the route to victory.

In 2015, the Conservatives claimed to have captured the pragmatic centre. They branded themselves the worker’s party and announced new policies such as a national living wage. This is an illusion. Such reforms merely disguise drastic changes to public services such as cuts in benefits and tax credits, increased private sector involvement in the NHS, and the permanent reduction of spending to US levels - around 35 % of GDP.

Conservative policies urgently require debate, but Corbyn’s victory leaves Labour without a credible voice. Meanwhile, cherished public institutions come under attack. Corbyn may have won the Labour leadership election, but it is clear that British voters are the losers.