Why a Shootout Between Black Panthers and Law Enforcement 50 Years Ago Matters Today

Members of the Black Panther Party outside the High Point property raided by police. Sonny Hedgecock/High Point Enterprise, CC BY-SA

Paul Ringel, High Point University

In the early hours of Feb. 10, 1971, police surrounded a property in High Point, North Carolina, where members of the Black Panther Party lived and worked. In the ensuing shootout, a Panther and a police officer were both wounded.

The incident did not receive much national attention at the time – armed conflict of this type was relatively common during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

But 50 years on, as the U.S. reckons with a year that saw militarized police confront Black Lives Matter protesters and fail to prevent an attack on the U.S. Capitol, I believe the circumstances of this shootout are relevant today.

As a historian who has interviewed participants in the confrontation for a coming book, I see the raid in the context of a then-emerging strategy of urban policing in the U.S., shaped by the racial and political clashes of the 1960s and forged through a growing partnership between local and federal law enforcement. That strategy, of criminalizing Black political activism at a time when white reactionary protesters were accommodated, has defined police responses to Americans’ activism – and political violence – over the past half-century.

Aggressive approach

The approach of law enforcement on the bitterly cold morning of Feb. 10, 1971, was aggressive and combative. Brad Lilley, the 19-year-old leader of the High Point branch of the Black Panthers, woke at 5 a.m. to discover about 30 police officers and sheriff’s deputies surrounding the rented house he shared with three other teenage members of the organization.

The police were seeking to evict the Panthers. Despite the fact that Lilley and the other members were paying rent on time, High Point police were looking to force them out in line with a national strategy of pushing Black Panthers out of communities because of their political activities. According to a High Point Enterprise local newspaper reporter on the scene, the force was “heavily armed and wearing flak jackets,” though none of the residents had a record of criminal violence. The Enterprise also questioned the police department’s aggressive strategy in the crowded residential neighborhood, stating “someone could have been killed in the comparative safety of his home.”

Ironically, High Point Police Chief Laurie Pritchett, who was on the scene that day, had previously built a national reputation by avoiding combative tactics. Pritchett had been chief in Albany, Georgia, in 1961 when the civil rights group the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee began organizing a movement to desegregate the city. His nonviolent approach to policing during this campaign largely thwarted those efforts, even after Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference became involved. King later called Pritchett “a basically decent man.” Some Black High Pointers described Pritchett’s approach on Feb. 10 as inconsistent with his generally nonbelligerent law enforcement practices.

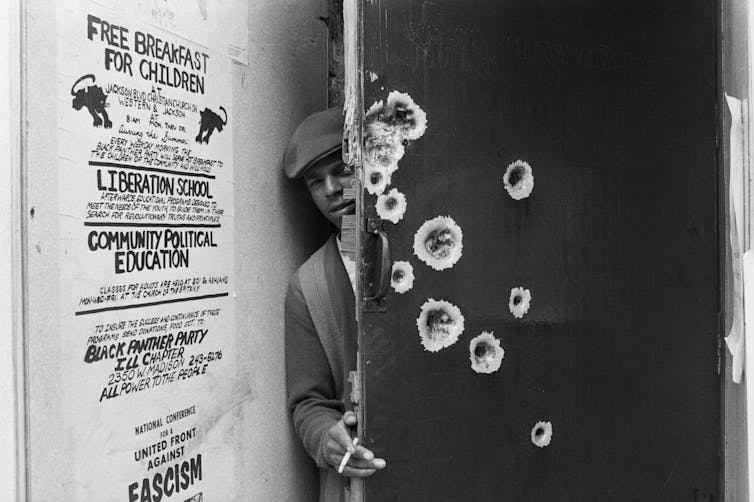

A member of the Black Panthers peeks around a bullet-pocked door that police blasted with gunfire during a predawn raid in Chicago. Bettmann/Getty Images

Interviews I have conducted suggest that the strategy of Feb. 10 exemplified Pritchett’s adoption of a more militant policing trend in the city. Lilley told me that just a few days before the shootout, a High Point police officer stopped his car and told him, “I know who you are.” According to Lilley and two other passengers in the car, the officer said he was a marked man and was going to be killed.

Surveillance and intimidation

Such targeting of leaders of the Black civil rights movement had become increasingly common for law enforcement since the FBI began surveilling King in 1963, and it accelerated after President Lyndon Johnson declared a “war on crime” in 1965. That surveillance, and the FBI’s COINTELPRO operation that sought to infiltrate Black revolutionary groups like the Panthers, reflected a shift in federal law enforcement’s response to the civil rights movement.

Previous Presidents Dwight Eisenhower and John Kennedy, respectively, had offered protection to the movement at pivotal moments, such as the desegregation of Little Rock’s Central High School and the Freedom Rides. Now the FBI was focused on disrupting and discrediting these organizations and particularly their leaders, echoing director J. Edgar Hoover’s 1968 warning to “prevent the rise of a ‘messiah’ who could unify and electrify the Black nationalist movement.”

This change aligned federal agents more closely with the practices of many local law enforcement institutions, and collaboration between the two groups flourished. The Law Enforcement Assistance Act of 1965 began the process of Congress’ providing “military-grade hardware” for local police departments. This trend has accelerated in the post-9/11 era, enabling local police to produce heavily militarized responses to anti-racism protests today.

Militant methods of policing Black activists also aligned with the violent treatment of left-wing and anti-war protesters at sites like the Chicago Democratic Convention in 1968 and Kent State University in 1970. Such aggressive tactics conveyed a perception of danger posed by left-wing and Black activists, an association that is still seen today in the different police responses to Black Lives Matter and anti-Trump protesters compared with that of right-wing activists. The Capitol attack shows the dangerous consequences of this tendency.

The law enforcement strategy against Black Panther leaders at the time also saw local and federal officers share information, with the FBI facilitating the Chicago Police Department’s killing of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton through an informant who shared information about Hampton’s activities and the layout of his apartment.

This partnership between local and federal agents contributed to the mistrust of law enforcement that already existed among Black activists. When the High Point police demanded that Lilley and the other Panthers exit the house that morning, they refused. Lilley remembers thinking about Hampton, as well as Bobby Hutton, the 17-year-old Panther shot at least 10 times by Oakland police in 1968 as he voluntarily surrendered.

This mistrust remains strong half a century later. A Feb. 2 poll revealed that just 36% of Black Americans trust the police, compared with 77% of white Americans.

Healing communities

When police threw tear gas and began moving toward his house in 1971, Lilley told me he was sure he would be killed.

He fired a shot that wounded one of the officers. The police responded with dozens of rounds of gunfire, and one of the Panthers was also wounded. Lilley subsequently served four-and-a-half years in prison for assault with a deadly weapon. He is now a pastor and activist in High Point, working to deescalate violence in the community.

Fifty years on from the police shootout, he said: “I find myself still in the struggle to help my community heal from the violence that is used against us.”

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Paul Ringel, Associate Professor of U.S. History, High Point University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.