Why We Should Be Frightened that the Story of Tamerlane Seems So Relevant

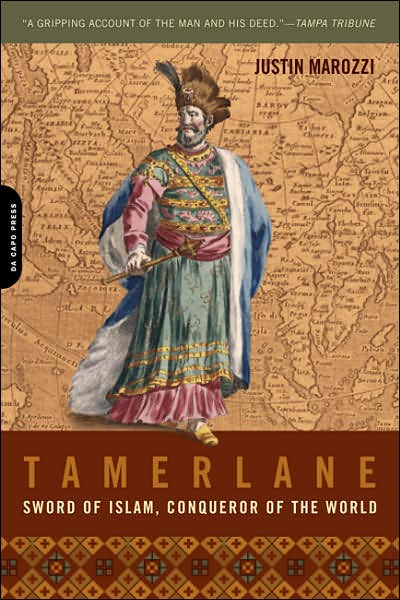

In the summer of 2004, I told a joke in Baghdad which completely bombed in front of a largely American audience of about 50. The occasion was the launch of the British edition of my book, Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conqueror of the World, and there was a grim appropriateness in the location. As I spoke, there was a dull baritone of mortars exploding and the staccato rattle of small arms fire across the city. Baghdad, once again, was at war. In 1401, the fourteenth-century conqueror had left the city, then known as Dar al Islam, the House of Peace, in ruins, girdled by 120 towers containing 90,000 severed heads of his latest victims.

My point, crudely made, was that however tragic the recent murder of a contractor, however ghastly his beheading, the situation in Baghdad had once been far, far worse. We needed to put our understandable horror at the atrocity into some sort of historical perspective. Decapitating the corpses of those men, women and children unlucky or foolish enough to stand in his way was Tamerlane’s battlefield signature. Its object was very simple: to strike fear into the hearts of his enemies. By and large, it worked. Tamerlane cut off heads on an industrial scale. He was never defeated in a major battle.

If this was a tactic of Tamerlane, it formed part of a much larger strategy. What drove him was conquest. How did he justify it, both to his weary armies – he campaigned for 35 years with only one significant break – and to his enemies? In a word, jihad.

Studying Tamerlane’s extraordinarily successful career, it is difficult not to find parallels with the modern era in which Muslim jihadists wage war against the West and, in Iraq at least, on each other. They key thing to understand is the flexibility with which the concept of jihad can be understood and therefore manipulated. If one’s enemy is Christian or Jewish, so much the better. Yet a Muslim enemy can be countenanced, too, because one can always consider that person a bad Muslim who has strayed from the path, and any innocent victims are destined for paradise anyway, so no need to worry about them. Thus, when Tamerlane offered a public justification for a particularly challenging campaign against India in 1398, he did so in the name of Islam. Never mind that his enemy was also Muslim. That didn’t matter.

“The sultans of Delhi have been slack in their defence of the Faith,” he told his amirs. “The Koran says that the highest dignity a man can achieve is to make war on the enemies of our religion. Mohammed the Prophet counselled likewise. A Muslim warrior thus killed acquires a merit which translates him at once into Paradise.”

Perhaps the most uncomfortable parallel, if you happen to be a jihadist, between Tamerlane’s holy war and the conflict raging in Iraq, is the number of innocent Muslims who meet their death at its practitioners’ hands. For all Tamerlane’s talk of killing the infidel, for all his posturing as a Ghazi (Holy Warrior) and the ‘Sword Arm of the Faith,’ he slaughtered far greater numbers of Muslims than Christians, Jews or Hindus. As the eighteenth-century British historian Edward Gibbon wrote in a typically dry aside, “If some partial disorders, some local oppressions, were healed by the sword of Timour, the remedy was far more pernicious than the disease ... perhaps his conscience would have been startled if a priest or philosopher had dared to number the millions of victims whom he had sacrificed to the establishment of peace and order.”

The same disregard for human life, notably of his fellow Muslims, was the hallmark of Abu Musab Al Zarqawi, the former leader of Al Qaeda in Iraq. Like Tamerlane, his victims were, whatever his rallying cry of jihad, disproportionately Muslim.

There is a second parallel, almost equally grim, between Tamerlane’s world and our own. Once again, it is in a Muslim country, this time Uzbekistan. President Islam Karimov, one of the world’s most brutal rulers, has made no secret of his admiration for Tamerlane. After seven decades of official vilification by the Soviets, who feared his nationalistic attraction to Uzbeks, six centuries after his death, Tamerlane has returned to the centre stage of Uzbek political life. Karimov has unveiled a statue of him in the heart of Tashkent, stuck his head on the highest denomination banknotes and newspaper hoardings, even equated himself with the conqueror in billboards of political propaganda. Tamerlane’s name has even been invoked on the war on terror, as in this quote from a member of the Uzbek Academy of Sciences:

“That which Amir Temur valued most – well-being, prosperity and, above all, peace and harmony – has been placed at the head of our independent republic’s agenda to safeguard against disorder and disturbance.”

The crackdown on human rights in Uzbekistan, briefly a key US ally in the War on Terror, has been ferocious. Does any of this sound familiar?