Mark Twain's Progressive and Prophetic Political Humor

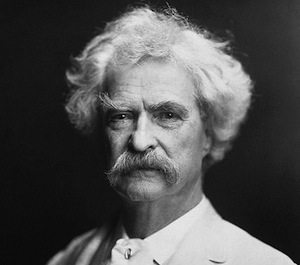

Mark Twain in 1907. Photograph taken by A.F. Bradley.

In the midst of a presidential campaign, with ads (and money to pay for them) flying left and right, what better time to recall Mark Twain? He was our first major stand-up political humorist. On one lecture tour in 1871-72, this author and public speaker/entertainer gave more than eighty speeches. Not only a humorist, he was also akin to a Jewish prophet criticizing his society for not living up to its principles. Thus, a major study of Twain as a radical social critic (by Maxwell Geismar) is entitled Mark Twain: An American Prophet.

In the midst of a presidential campaign, with ads (and money to pay for them) flying left and right, what better time to recall Mark Twain? He was our first major stand-up political humorist. On one lecture tour in 1871-72, this author and public speaker/entertainer gave more than eighty speeches. Not only a humorist, he was also akin to a Jewish prophet criticizing his society for not living up to its principles. Thus, a major study of Twain as a radical social critic (by Maxwell Geismar) is entitled Mark Twain: An American Prophet.

Lines like "Reader, suppose you were an idiot, and suppose you were a member of Congress. But I repeat myself" are not far from the feelings of many present-day voters. Pulitzer-Prize-winning historian Garry Wills once wrote that "to understand America, read Mark Twain. ... No matter what new craziness pops up in America, I find it described beforehand by him." He also referred to Twain's first novel, The Gilded Age (1873), co-written with Charles Dudley Warner, as "our best political novel." Historians have applied the novel's title to describe an era with some similarities to our own: the nineteenth-century decades following the Civil War, an era of greed, plutocrats, unbridled capitalism, and political corruption that occurred before the more reformist Progressive Era.

In his half-century writing and speaking career Twain was not always as outspoken as some modern-day progressives might like. Nor was he always consistent or right or free of the faults he satirized in others. In many of the views expressed in the last two decades of his life (1890-1910), however, on topics ranging from women's suffrage to imperialism and war, he was progressive indeed.

In 1901, almost two decades before women obtained the vote in U. S. national elections, he told an audience, "For twenty-five years I've been a woman's rights man. ... I should like to see the time come when women shall help to make the laws. I should like to see that whip-lash, the ballot, in the hands of women." And less than a year before his death, he said in a newspaper interview: "As to the militant suffragettes, I have noted that many women believe in militant methods. You might advocate one way of securing the rights and I might advocate another, they both might help to bring about the result desired. To win freedom always involves hard fighting. I believe in women doing what they deem necessary to secure their rights." (See here for the sources of many of the quotes below.)

In an edited collection, Mark Twain and the Three R's [Race, Religion, and Revolution], the section on Race contains numerous examples of Twain's criticisms of racism, both in the USA and abroad. Because of the use of words like "nigger" in Huckleberry Finn, Twain has sometimes been accused of being racist, but that fails to properly consider the work's historical and literary context. One of Twain's most recent biographers (Fred Kaplan) cites Booker T. Washington's comment about Twain's "sympathy and interest in the masses of the Negro people." This same biographer writes that "Twain strongly believed that white America owed reparations to black America," and he quotes Twain writing: "Whenever a colored man commits an unright action, upon his head is the guilt of only about one-tenth of it, and upon your heads and mine and the rest of the white race lies fairly and justly the other nine-tenths of the guilt." In a scathing and satirical 1869 editorial attributed to Twain, he lambasted a Memphis lynch mob who had lynched an innocent black man. In 1901, in response to a Missouri lynching he wrote (but decided not to publish) The United States of Lyncherdom.

By the mid-1880s, Twain was sympathetic with workers' efforts to unionize and told the Knights of Labor union in 1886: "Who are the oppressors? The few: the king, the capitalist, and a handful of other overseers and superintendents. Who are the oppressed? The many: the nations of the earth; the valuable personages; the workers; they that Make the bread that the soft-handed and idle eat." Months before his death in 1910, Twain told his good friend William Dean Howells that the unions were the "sole present help of the weak against the strong."

Twain was also concerned about human rights in other countries. He criticized the treatment of the Jewish Captain Dreyfus in France during the Dreyfus Affair, contributed to raising funds for Jewish pogrom victims in Russia, and criticized oppressive measures of the Russian tsarist government (see, e.g., his Czar's Soliloquy).

In his approach to politics and political leaders he was generally in tune with the Progressive movement of the twentieth century's first decade, but was more akin to the Progressive muckraking journalists than to Theodore Roosevelt, who criticized them and was anathema to Twain.

In 1906 (according to the first volume of a new and less inhibited edition of Twain's Autobiography), he dictated this:

The McKinleys and the Roosevelts and the multimillionaire disciples of [business tycoon] Jay Gould -- that man who in his brief life rotted the commercial morals of this nation and left them stinking when he died -- have quite completely transformed our people from a nation with pretty high and respectable ideals to just the opposite of that; that our people have no ideals now that are worthy of consideration; that our Christianity which we have always been so proud of -- not to say so vain of -- is now nothing but a shell, a sham, a hypocrisy; that we have lost our ancient sympathy with oppressed peoples struggling for life and liberty (462).

By this time he had soured on American civilization. With some sarcasm and irony he wrote:

We are wonderful, in certain spectacular and meretricious ways; wonderful in scientific marvels and inventive miracles ... wonderful in its hunger for money, and in its indifference as to how it is acquired ... wonderful in its exhibitions of poverty ... in electing purchasable legislatures, blatherskite Congresses, and city governments which rob the town and sell municipal protection to gamblers, thieves, prostitutes, and professional seducers for cash. It is a civilization which has destroyed the simplicity and repose of life; replaced its contentment, its poetry, its soft romance-dreams and visions with the money-fever, sordid ideals, vulgar ambitions, and the sleep which does not refresh; it has invented a thousand useless luxuries, and turned them into necessities; it has created a thousand vicious appetites and satisfies none of them.

Although our consumer culture was still in its early days, Twain already perceived how characteristic it was becoming of our overall culture.

Like other contemporary critics of imperialism such as Joseph Conrad, Leo Tolstoy, and Mohandas Gandhi, he realized how Western countries were using the term "civilization" itself as an excuse to sell goods abroad and to justify their "civilizing" imperialistic ventures. Gandhi referred to the "disease of civilization" and observed that "if people of a certain country, who have hitherto not been in the habit of wearing much clothing, boots, etc., adopt European clothing, they are supposed to have become civilized out of savagery." Twain thought along the same lines and wrote, "Civilization is a limitless multiplication of unnecessary necessities."

In 1898, the year of the U.S. annexation of Hawaii and the taking of the Philippines in the Spanish-American War, political orator and soon-to-be senator Albert Beveridge declared: "American factories are making more than the American people can use; American soil is producing more than they can consume. Fate has written our policy for us; the trade of the world must and shall be ours. ... We will establish trading-posts throughout the world as distributing points for American products." About the Philippines, President McKinley added: "There was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them."

In opposition to this war of 1898, Twain joined with others in the newly-formed Anti-Imperialist League, of which he later became vice-president. The League and he publicized atrocities committed by U.S. troops (see e.g. here and here) in their war to put down Filipino guerrilla forces resisting the U.S. takeover.

Of war in general, he was often critical. In his "The War Prayer," occasioned by our fighting in the Philippines, he satirized those who asked God's blessings for their war efforts -- "O Lord our God, help us to tear their soldiers to bloody shreds with our shells; help us to cover their smiling fields with the pale forms of their patriot dead; help us to drown the thunder of the guns with the shrieks of their wounded, writhing in pain; help us to lay waste their humble homes with a hurricane of fire; help us to wring the hearts of their unoffending widows with unavailing grief; help us to turn them out roofless with little children to wander unfriended the wastes of their desolated land in rags and hunger and thirst."

Twain was also critical of numerous other imperialistic activity, especially King Leopold of Belgium's scandalous policies in the Congo. Twain's scathing "King Leopold's Soliloquy" (1905) was only part of his effort to put an end to the suffering, mutilations, and deaths of millions of Congolese. He also lobbied Washington politicians, including President Roosevelt, to take actions, and gave speeches about Congo atrocities. Sometimes speaking along with him was Booker T. Washington, who said about Twain, "I think I have never known him to be so stirred up on any one question as he was on that of the cruel treatment of the natives in the Congo Free State."

Although not all of Twain's progressive social and political writings, speeches, and quips were humorous, many of them were. He appreciated the following words from William Thackeray's essay on Jonathan Swift: "The humorous writer professes to awaken and direct your love, your pity, your kindness -- your scorn for untruth, pretension, imposture -- your tenderness for the weak, the poor, the oppressed, the unhappy. ... He takes upon himself to be the week-day preacher." Although Twain was often critical of organized religion, he had a very close friend who was a minister and was himself a secular moralist who believed that humor had to serve an "ideal higher than that of merely being funny."

His friend Howells wrote in 1880, that Twain's humor sprung "from a certain intensity of common sense, a passionate love of justice, and a generous scorn of what is petty and mean." Howells also suggested that much of Twain's humor was based on the incongruity between words and deeds. In his "The War Prayer" the incongruity of asking God to inflict suffering upon women and children is evident.

Politics, religion, and the rich especially offered Twain material for his humor of incongruity because of the discrepancies they often presented between pious platitudes and unseemly behavior. He enjoyed, for example, writing about John D. Rockefeller Sr. and Jr., both of whom taught Bible classes. Twain mentioned that the father did not pay his fair share of taxes and took delight in the son's trying to explain away Christ's admonition to a young man, "Sell all thou hast and give it to the poor." (In Roughing It Twain wrote humorously of his encounters with Mormons and added an appendix on their history.) Time after time, whether in regard to religion, earning money, seeking and holding political office, slavery, race relations, imperialistic adventures, or war, Twain poked fun at incongruities between words and actions.

In the words of one scholar (Harold K. Bush), Twain's humor rebelled against "whatever seemed rigid and regulating to mind and identity: any confining orthodoxy, whether political, religious, aesthetic, imaginative, or even biological." Howells wrote of Twain's humor being aimed at oppressors and hypocrites.

As indicated at the beginning of this essay, Twain was a prophet in the sense of being one who criticized the social and political order for failing to live up to its ideals. Decades after his death, two important prophetic voices commented on the importance of humor and prophecy for any society. The first was Reinhold Niebuhr (1892-1971), perhaps the twentieth century's most influential U.S. theologian. He wrote that "a sense of humor is indispensable to men of affairs who have the duty of organizing their fellowmen in common endeavors. It reduces the frictions of life and makes the foibles of men tolerable. There is, in the laughter with which we observe and greet the foibles of others, a nice mixture of mercy and judgment, of censure and forbearance." Niebuhr thought that meeting "the disappointments and frustrations of life, the irrationalities and contingencies with laughter, is a high form of wisdom."

The second prophetic voice was that of the Trappist monk and prolific author Thomas Merton (1915-1968). True prophets, he thought, advocated "the destruction of the inequalities and oppressions dividing rich and poor; conversion to justice and equity." He thought that American society was "organized for profit and for marketing," and added that "this is the system that calls for some kind of prophetic response."

In this major election year Twain's satirical and prophetic example is more needed than ever. Garry Wills, who thinks Twain so prescient, writes "this election year gives Republicans one of their last chances -- perhaps the very last one -- to put the seal on their plutocracy." Such a form of government dominated by wealthy interests was one of the major targets of Twain during the last decade of his life. A New York Times review of the first volume of the new edition of Twain's Autobiography observes that it is "unsparing about the plutocrats and Wall Street luminaries of his day."

Comedians such as Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert (who once interviewed Wills) have recently satirized Mitt Romney, with Stewart pretending to have access to reams of Romney's back tax returns. And Romney and his plutocratic supporters are indeed an inviting target for such Twainian satire, as I have indicated in an earlier piece. But the Obama campaign is also fair game whenever it departs from the ideals the president proclaims. As Twain himself once stated, "The political and commercial morals of the United States are not merely food for laughter, they are an entire banquet."