Clint (and Mitt), What Were You Thinking?

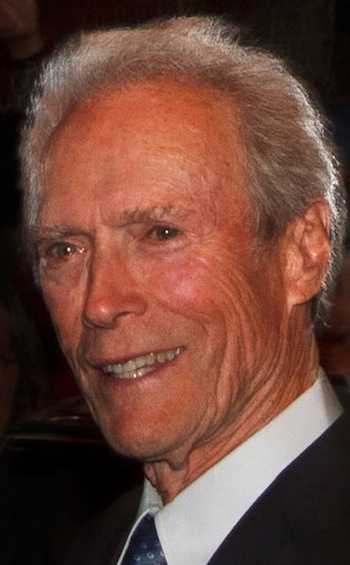

Clint Eastwood at the 2010 Toronto International Film Festival. Credit: Flickr.

Mitt Romney constantly reminds voters that he knows how to govern effectively because he had been a successful businessman. But during one of the most important evenings of his presidential campaign -- the night he delivered an acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention -- Romney fumbled. He allowed Clint Eastwood to address the nation shortly before his own speech. Romney and his top convention aides did not know how the famous Hollywood actor intended to handle the situation.

Mitt Romney constantly reminds voters that he knows how to govern effectively because he had been a successful businessman. But during one of the most important evenings of his presidential campaign -- the night he delivered an acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention -- Romney fumbled. He allowed Clint Eastwood to address the nation shortly before his own speech. Romney and his top convention aides did not know how the famous Hollywood actor intended to handle the situation.

The events of that night do not inspire confidence in Mitt Romney’s skills as a planner, organizer, and leader.

When journalists blasted Clint Eastwood’s speech as weird and inappropriate, Romney’s aides quickly tried to clear themselves and their candidate of blame. Yet Eastwood was on the stage primarily because Mitt Romney wanted him there. Romney was deeply impressed by Clint Eastwood’s impromptu talk at a fundraising event in Sun Valley, Idaho. “He’s just made my day. What a guy!” exclaimed Romney. The Republican candidate then secretly made arrangements for Eastwood’s appearance at the convention.

How could Mitt Romney and his key advisers commit a primetime slot in their carefully-scripted program to an un-vetted performance? They had not scheduled a rehearsal. Aides reminded Eastwood of talking points, but they generally allowed him to improvise. Eastwood did, indeed, ad-lib. Just minutes before beginning the routine, he surprised a stagehand by requesting that a chair be placed on the set.

Pundits have rightly characterized Clint Eastwood’s sketch as disrespectful to both the president and the vice president. Eastwood’s theatrical dialogue with the empty chair suggested that Obama told him to “shut up.” The actor asked, “What do you want me to tell Romney?” ... “I can’t tell him that, He can’t do that to himself.” Eastwood then ripped into the vice president. “Of course we all know Biden is the intellect of the Democratic Party,” he remarked sarcastically. “Just kind of a grin with a body behind it.”

Many convention delegates laughed at the one-man, one-prop show, but lots of television viewers and journalists were alarmed.

How low can politics go, they asked? Is this the way to speak publicly about the president and vice president (or for that matter, any candidate of any party for national office)? The actor did not seem to recognize that his effort to talk trash and draw laughs might upstage and undercut Romney.

Eastwood has received the brunt of criticism for this embarrassing episode, but that assignment of blame is not entirely fair. Clint Eastwood is a fine movie director and actor but not a seasoned politician (although he served in the 1980s as mayor of little Carmel-by-the-Sea). Eastwood did not appreciate how much his performance could backfire, embarrassing the GOP and alienating many viewers. Romney’s aides, who meticulously planned the convention activities, could have saved him from trouble by scheduling rehearsals and offering guidance.

True responsibility for the unfortunate event was in the hands of the presidential candidate. Mitt Romney wanted to surprise the delegates and television viewers with a presentation by a secret guest. Romney gambled recklessly when he made that decision. He did not perform “due diligence,” i.e., the kind of research and analysis that a smart businessman ought to engage in before investing.

If Romney operated Bain Capital in the manner that he handled preparations for one of the most important moments in his political life, critics might judge him a poor executive.

This is not the first time the GOP’s presidential candidates and election strategists revealed serious organizational shortcomings.

Some past errors related to convention speeches. For instance, President George H. W. Bush lost precious ground at the 1992 G.O.P. convention when Pat Buchanan alienated moderate voters with an address that seemed to welcome a culture war.

The Grand Old Party has also been troubled by its presidential candidates’ poorly researched decisions about running mates. George H.W. Bush chose Dan Quayle in 1988 as the vice presidential candidate, evidently because of Quayle’s youth and good looks (ironically, Bush was also considering Eastwood). But Quayle quickly showed inadequate preparation for national leadership. In 2000 George W. Bush took the unusual step of allowing the head of his VP search committee to become his running mate. Dick Cheney later overshadowed Bush at the White House and delivered poor advice to the president. Cheney left office with an exceptionally low public approval rating. And, of course, John McCain chose Sarah Palin in a rushed, last-minute decision. When Palin had to answer questions from the media, it became evident that McCain and his campaign team had not done their homework.

Clint Eastwood’s theatrics during the last night of the G.O.P. convention will probably not damage the Republican Party’s campaign for the White House. But news about the haphazard way Mitt Romney planned this event raises a question about his vaunted leadership skills.