Watch the Polls -- Where People Vote

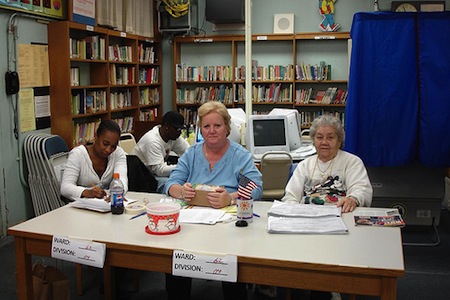

Election workers in Philadelphia's 62nd Ward, 4th Division, on Election Day 2008. Credit: Flickr/David Webber.

If I had been Al Gore's campaign manager in 2000 and he had listened to me, he would have defeated George W. Bush for president. My prime directive would have been simple. Even at the cost of spending less money on television spots, focus groups, and tracking polls, make sure that you have plenty of flesh-and-blood representatives at the polls where people vote in order to prevent intimidation and help with complicated ballots.

This advice -- which is equally relevant to the 2012 election -- would not have been the product of my day job as a professor of history but rather the result of my experience as a young poll watcher for Eugene McCarthy delegates in the April 1968 Connecticut Democratic primary. There I learned that a lot of ballots get screwed up, a non-academic term used here to embrace spoiled, stray, null, over-voted, under-voted, residual and other technical categories favored by scholars who study this problem as part of their day jobs.

As with much Election Day activism my decision to watch polls in 1968 was rooted in a combination of idealism, self-interest, and fond memories. I respected McCarthy for opposing the Vietnam War, wanted a small break from writing seminar papers at Yale graduate school, and thought the pay looked good -- about $30 if I recall rightly, no mean sum for a grad student in those days. Equally important, the mystique of Election Day that had taken hold of me when I was a kid and survived amid my moderately New Left worldview at age 22.

My uncles Tony and Jim, brothers-in-law and good friends, were respectively Republican and Democratic leaders in Ward 1 of Paterson, New Jersey during the early 1950s. The friendship was hardly incongruous since urban politics in that era lacked ideological rigor. As Tony told me decades later, he had joined the local Republicans because they sponsored livelier social events. This explanation fitted Tony’s personality but, since he was also a small businessman, sounded less than fully convincing. Still, party affiliation probably did not count for much. As Tony also recalled, "everybody" voted for FDR and for Mike De Vita, the neighborhood boy elected Paterson’s first Italian American mayor in 1948.

In the early 1950s Tony and Jim hired their relatives, including my father, as poll watchers, which involved checking in voters and advising them on how to use the mechanical voting machines. These machines had become standard in most cities since their introduction in the 1890s. Voters pulled a big lever to close the curtain, clicked the small levers beside the names of their favored candidates -- or perhaps just the slightly larger "party lever" -- and then pulled the big lever again simultaneously to open the curtain and record their votes. Sometimes I was allowed to hang around for a while on Election Day. I particularly liked to play with the little model voting machine the poll watchers used to instruct voters. At least once my father took me into the curtained-off voting booth and allowed me to click the levers for him.

Although the "new politics" organizers for McCarthy knew nothing of my poll watcher nostalgia they could not miss my Italian-sounding first and last names. Names ending in vowels were rare among McCarthy poll watchers in New Haven, not least because our ranks drew disproportionately from Yale graduate students. Accordingly, after a brief introduction to Connecticut voting law I was appointed head McCarthy poll watcher in a heavily Italian American ward. My job was to prevent chicanery by the regular Democrats.

This ward assignment made sense. I was certainly less likely than most new politics adherents to regard the locals as dangerous “authoritarian personalities" because of their ethnicity or their support for the Vietnam War. Pat (ne Pasquale), the Democratic ward leader and head poll watcher for the regulars, reminded me of my uncles. His assistants reminded me of my cousins. Luckily the regulars provided Italian sandwiches for everybody. The need for food during our dawn to early evening poll watching was a mundane matter ignored by the new politics insurgency. Even in 1968 this lapse seemed symbolic of a broader obliviousness to reality.

Despite our generally good relations Pat and I sometimes clashed. The most frequent disagreements involved the old men and women with heavy Italian accents who reminded me of my great aunts and great uncles. After they pulled the big lever and the curtain closed off the voting booth, many of them panicked. At first I was surprised by their panic but after a while the problem seemed almost routine. The question at hand was what to do. Many of those who panicked asked Pat to breach the curtain, click the levers on behalf of the regular party slate, and get them out of there.

Under ordinary circumstances, Pat would have done just that. The presence of McCarthy poll watchers changed the dynamic. At most, we insisted, Pat and I could breach the curtain in tandem and give generic advice about how these claustrophobic voters could cast some sort of vote and escape. I upheld the law and the cause of the McCarthy insurgency though not without mental reservation. After all, I was hoping that these distressed men and women would thrash around, perhaps accidentally vote for my side, or just flee the booth without voting. In some cases my hopes were fulfilled.

The Connecticut election was not strictly speaking a presidential primary. Rather, voters chose some of the delegates to the state convention that would in turn select delegates to the national convention. The McCarthy slate carried New Haven. It lost in my ward but did much better than either side expected -- and not because most voters were confused by the ballot. Even people whose names ended in vowels had begun to turn against the Vietnam War. The mainstream media made one of its periodic discoveries of grassroots activism noting that even graduate students could influence elections. I was delighted. But since April 1968 I have never doubted that a lot of votes get screwed up.

According to standard estimates 2 percent of votes in presidential elections are not recorded for one reason or another. The partial Florida recount in 2000 highlighted this general problem along with the specific issues of confusing ballots and voter intimidation. After the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Bush v. Gore brought the recount to a precipitous end, state officials declared George Bush the winner by 537 votes. If the Democrats had spent a few hundred thousand dollars to organize and train a few thousand poll watchers, especially in African American neighborhoods, Al Gore probably would have carried Florida by a small but comfortable margin and won the presidency.

During the 2000 controversy Americans learned that votes cast on computer punch cards could be invalid due to hanging chads (holes partially punched through) and pregnant chads (incomplete punches leaving dimples rather than holes). Because of the confusing ballot in Palm Beach county Reform party candidate Pat Buchanan received at least several hundred votes from Gore supporters.

Twelve years later ballots are still a mess in many if not most places. Since moving to Washington, D.C. in 1973 I have voted via ever-changing computer systems. Sometimes I have filled in circles with a pencil. Sometimes I have used a pencil to connect two parts of an arrow. Sometimes I have punched holes in computer cards; the cards did not always fit easily into the hole punching gizmo but I have done my best to avoid hanging or impregnating chads. Although old mechanical voting machines are still used in a few places no one manufactures replacements. Despite the problems I saw in New Haven, I urge their come back under the advertisement: "Your grandfather's voting machine. They can only steal or screw up one precinct at a time."

One of the most hypocritical rituals of American politics is the frequent declaration that everyone eligible should vote and everyone's vote should count. My uncle Jim might have called these ritual declarations blarney though, long since assimilated out of his familial Irishness, he probably would have chosen a more pungent adjective also beginning with "b." Discouraging, suppressing, and deliberately miscounting votes constitutes a venerable American tradition. Effective techniques have included poll taxes, literacy tests, onerous registration requirements, burdensome restrictions on ballot access, intimidation, violence, and murder. African Americans have endured the strictest and deadliest forms of voter suppression. In addition, however, from the so-called Progressive era through the 1920s many liberals joined conservatives in trying to limit the power of poor and working class voters in the name of honesty and good government.

In recent years this ignoble tradition has been sustained almost entirely by conservatives and, as conservatives have increasingly quit the Democratic Party, almost entirely by Republicans. The favored scheme of the moment is legislation requiring a photo ID to vote. The exact type of ID and degree of racial discrimination intended vary from state to state. Supporters of President Obama have challenged some of these laws on the grounds that they violate civil rights protections. Even if every law is struck down or significantly modified in application, an unlikely event, the ID campaign will have served its partisan purpose -- to deter timid voters from going to the polls, insisting on the adequacy of their identification, or asking for explanations of perplexing ballots.

So we return to the issues of intimidation and confusion on election day. While effectively litigating and (probably less effectively) pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into television spots, the Democrats seem no more attentive to face-to-face politics than they were in 2000 and recent polls showing President Obama ahead of Mitt Romney are likely to foster unwarranted complacency. They still have time to change their ways before November 6. Feisty and friendly poll watchers not only can prevent intimidation, but they also can make a converted school cafeteria or church basement feel hospitable. Equally important, these officials can offer help understanding the ballots and the gizmos used to record the votes. Outside the polling places, just beyond the distance mandated by law, the parties still swamp incoming voters with pamphlets in hope of swaying the undecided. Especially since undecideds in this presidential election are few and far between, these unofficial poll nudges can perform a better service by putting aside their formulaic flyers and offering voter orientation via sample ballots.

In 2012 my campaign advice goes to Barack Obama instead of Al Gore. But Romney, Green candidate Jill Stein, and Libertarian Gary Johnson should also consider my recommendations. I actually do believe that people should be helped to vote as they wish and have their votes counted. This idealism is my penance for watching the old Italian Americans thrash around in the New Haven voting booths forty-four years ago.