Picturing James Baldwin in Exile

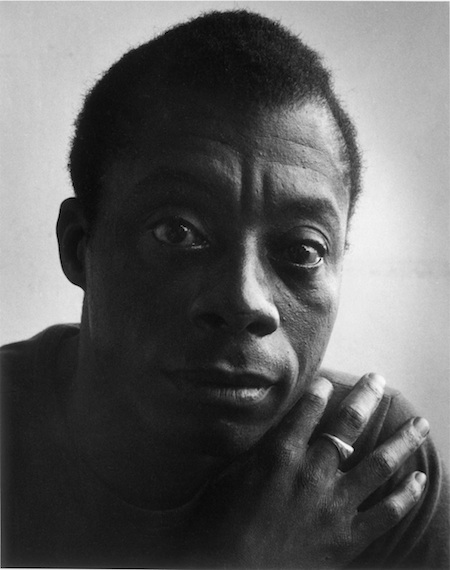

1964 portrait of James Baldwin. All photos courtesy of Sedat Pakay.

Being out . . . one is really not very far out

of the United States . . . One sees it better

from a distance . . . from another place,

from another country.

-- James Baldwin

James Baldwin (1924-1987), the renowned American novelist, essayist, playwright, civil rights advocate and social critic, was an outspoken advocate for equality and respect for all citizens regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or sexual preference. His novels include Giovanni’s Room, Go Tell It on the Mountain, and Another Country, but he may be most remembered for his powerful essays, often reflections on the timeless American obsessions with race and sexuality, found in his books such as Notes of a Native Son, The Fire Next Time and Nobody Knows My Name.

Baldwin was at the height of his career in the early 1960s -- and the demands of admirers and critics alike grew so overwhelming that he was often unable to work in his native land. A celebrity, a public intellectual and an inspiring leader, Baldwin was doubly cursed in the U.S. for being both black and gay.

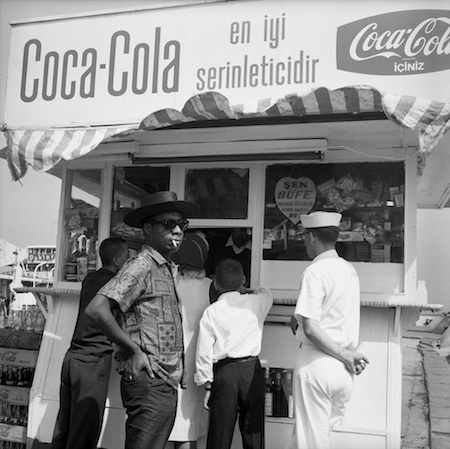

From 1961 to 1971, when the civil rights revolution and anti-war movement embroiled America and demands on Baldwin’s time were unceasing, he often sought refuge in Turkey to write and enjoy a less frenzied and more contemplative life.

At age nineteen, a young Turkish photographer, Sedat Pakay, met Baldwin in Istanbul, photographed him, and became a close friend. Since then, Pakay has become an internationally acclaimed photographer.

Now, Seattle’s own Northwest African American Museum (NAAM) is hosting a rare exhibition of dozens of Pakay’s candid photographs of Baldwin from that historic epoch as well as his short documentary of Baldwin in Istanbul, In Another Country. The images in reveal a much more relaxed, happier, funnier and more reflective man than usually portrayed in the American media at the time, and make vivid again this iconic artist and activist. You see Pakay’s friend “Jimmy” in unguarded moments: working at his typewriter, apron-clad in a kitchen, clowning with friends, lost in thought, napping, and even eying a friend’s pet pelican.

Many of Pakay’s photos as well as tributes to Baldwin are included in the exhibition catalog James Baldwin in Turkey: Bearing Witness from Another Place -- Photographs by Sedat Pakay and Foreword by Charles Johnson (University of Washington Press).

This unprecedented show of Baldwin photographs by Sedat Pakay will be on display in Seattle at the Northwest African American Museum (2300 South Massachusetts Street, Seattle, WA 98144) until September 2013.

Barbara Earl Thomas, the museum’s executive director -- and nationally renowned visual artist and writer -- recently described the series of events that brought the premiere of this heralded show to NAAM.

Thomas explained that Howard Norman, the University of Maryland professor, novelist (The Bird Artist, Devotion, What is Left the Daughter) and a personal friend of Pakay, was in Seattle a couple of years ago for a reading at Elliott Bay Book Co.

Norman called Thomas and told her about “these wonderful photos by Sedat Pakay who, as a young person in Turkey, met James Baldwin and ended up chronicling his life.” And Norman insisted, “I think the Northwest African American Museum would be a great place to have the show.”

Thomas recalled telling Norman that “we were a small, very modest place and you could go anywhere,” but Norman responded “No. I think the Northwest African American Museum is the place to do it.”

Then, at Pakay’s invitation last year, Thomas and Brian J. Carter, NAAM’s assistant executive director and exhibition curator, traveled to Pakay’s home in the Hudson Valley of New York, met Pakay and reviewed hundreds of his slides, contact sheets, and photographs of Baldwin as well as his documentary on Baldwin.

After reviewing Pakay’s rich material, Thomas and Carter decided to do a show. Thomas said that Carter visualized the show and put it together but, she added, “I take credit for being captivated by the idea and pursuing it.”

Sedat Pakay was born in Turkey in 1945. He went on to Yale where he studied art and received his Masters in Fine Arts in 1968. Pakay has worked as a photojournalist for various magazines including Holiday, Esquire, and New York. He also made documentary films about his friend and mentor at Yale, the eminent photographer Walker Evans, as well as artist Josef Albers. His photographs are in international private and museum collections including those of The Museum of Modern Art, Smithsonian, Museum of Turkish-Islamic Arts, Getty Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin, Istanbul Modern Art Museum and Lehigh University. He lives with his wife in Hudson, New York.

* * * * *

How did you meet James Baldwin?

Sedat Pakay: I met him in 1964, the year I finished high school at an American school [in Istanbul] called Robert Academy, a part of Robert College.

I saw an item in one of the newspapers that said “Famous American Writer Visiting Istanbul.” Immediately, I wanted to photograph this man because he had a fabulously photogenic face. I collect faces. I like doing portraiture and faces and people fascinate me.

You were already a photographer then?

I was a novice. This was really my first trial at photographing somebody well known. I went in without any expectation that [the photographs] would be sought after. I didn’t really know about him and hadn’t read any of his books.

Through a friend, my art teacher, I got to the people he was staying with. I asked if I could photograph Jimmy Baldwin and they said fine. It was a very easy assignment. I asked him to sit here, sit there, move your hand, move your head. He complied and he was very nice.

Later, I read about him and, my goodness, I was nineteen years old and [directing] this seasoned writer and well-known personality.

He was immediately quite comfortable with you?

He was. I wasn’t pushing. I’m basically of the school of photojournalists who didn’t want to show themselves to the world. For example, the photographer Cartier-Bresson who refused to have his picture taken and didn’t want anybody to know who he is.

Throughout the years that I photographed Jimmy, I was just a witness in his scene. He was comfortable, and did whatever I asked because he knew I wasn’t exploiting him and he was very cooperative.

Your unobtrusive approach must be the secret to these intimate photographs where you capture Baldwin napping, reflecting, working, and clowning. How did Baldwin come to Turkey and what enthralled him about it?

Engin Cezzar, who he stayed with, went to Yale Drama School. He’s an actor/ director. He went to New York, waited tables, and then he went to Actor’s Studio where Baldwin was writing a play, and they became good friends.

Engin returned to Turkey and married a well-known actress and they were a theatrical power couple. When Baldwin was trying to finish Another Country [Engin] invited him to come to Istanbul for peace of mind. So he lived with him and finished Another Country. [Baldwin’s biographer] David Leeming met Baldwin in a party [in Istanbul] and he said, “It’s finished, baby.” Later on [Baldwin] said that finishing Another Country was like giving birth to a baby after ten years of pregnancy.

How did you become a member of Baldwin’s inner circle in Turkey?

After I met and photographed him, I had a show at Robert College about a Turkish painter Aliye who was very blonde and I opened that show called “Aliye and Jimmy.” Jimmy was the opposite: dark and not a great beauty whereas this woman was. The show opened, and I gradually made friends and I was invited to meet his friends, Engin Cezzar and his wife.

So I knew these people and other artists and newspaper people, but luckily no photographers. I had the camera and nobody else had one. I was able to photograph and catch him in my quiet way without any forceful interruption.

Wasn’t Baldwin traveling frequently between Turkey and the United States from 1961 to 1971?

He was traveling. Many of the pictures in the exhibition are from 1966 when he rented a villa on the Bosporus and was writing the novel Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone. There are shots of him pecking away on what I tell young people is a machine from the twentieth century called the typewriter.

A funny thing happened. At the end of 1966, I was accepted to Yale Art School. The American Consulate [in Turkey] wanted an affidavit of someone to support me so I wouldn’t be a burden to anyone if I didn’t have money. The only person I knew was Baldwin, and I said, “Jimmy, would you mind giving me this document they require?” He said, “Not at all.”

We went to the consulate and still say I wish I’d had a camera. These two huge Marines guarded the consulate and Baldwin walked between them. Jimmy was small: five feet and very skinny. It was a funny sight to me that there was such a major contrast.

So I was in New Haven at the Yale Art School, and whenever Baldwin was in New York, I’d go and see him. I’d go with him and his second youngest brother David who was like his bodyguard to protect Baldwin from any evils that might come his way. And he would leave and go back to Turkey and to France, zigzagging back and forth over the Atlantic Ocean.

And this was at the height of the civil rights movement in the United States, yet Baldwin chose to often leave the country?

He was already active in that earlier than his arrival in Istanbul. My theory is that he was not really free to write his books in New York. There were always interruptions and he was pulled in every different direction. He was invited to four or five dinners every night and he couldn’t say no. The first would end at twelve, and then he’d go to the second dinner, and by five o’clock, more or less finish this round with the proper amount of Scotch.

He was a big celebrity. People would come to our table to get his autograph and he was always dressed as a dandy [with] this scarf around his neck and beautifully dressed. He knew he was at the top of the world, and he acted as such.

And he was also sought out by the media.

Yes. He was in many programs. There was one with [conservative commentator] William Buckley. It was difficult for both of them. They were ready to have a fistfight. Buckley was a son of a bitch to start with, and he was really nasty to Baldwin, especially on racial issues. Baldwin was very quick on his feet and he was trying to answer and tear down the references that Buckley used and Buckley was not pleasant or polite.

Was Baldwin open about his sexuality?

He was very open and everyone knew he was gay. There was a wonderful interview with a BBC reporter who said, to the effect, “Mr. Baldwin you are a Negro and you’re such and such and you are a homosexual.” And Baldwin said, “Baby, I hit the jackpot.”

You note that celebrities often visited him.

Yes. Marlon Brando visited him in Istanbul. He and Brando had worked together at the Actors Studio in New York and they were good friends.

In 1970, I stayed with him in L.A. where he was writing a screenplay for Malcolm X based on the book by Alex Haley, who first interviewed Malcolm X for Playboy magazine [and] then wrote The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Baldwin moved to L.A. and I had a tough photography assignment in upstate New York. I was exhausted and I asked Jimmy if he minded if I come to stay in L.A. He said come on over.

I flew there the next day and went to this house in the Hollywood Hills and stayed with him. He had a young Frenchman from Marseilles accompanying him. He always had young guys from England and France hanging around. I became the third person in the house. One of my duties was to take this French guy around L.A. just to keep him busy when Baldwin would go to the studio and work on the screenplay.

He was assigned a screenwriter from New York, Arnold Perl, who was a well- known writer who was blacklisted. His best-known work was the TV series East Side, West Side. A lot of Arnold Perl’s friends were also blacklisted like George C. Scott, Zero Mostel, and Lee Grant. A Yiddish writer, Shalom Aleichem, has a very short play called Tevye and His Daughter. Arnold expanded this play into a Broadway musical that became Fiddler on the Roof.

A lot of people came to visit Baldwin then. Billy Dee Williams, who wasn’t a star then and was doing police shows, was at the house every day because he wanted to play Malcolm X. And others wanted to play Malcolm X like Raymond St. Jacques and Roscoe Lee Brown.

During that time, Baldwin often had lunch guests. Once I sat there with [French actress] Simone Signoret, a friend of his from Paris. I cursed my fate because I didn’t speak French and there was an enjoyable conversation going on, and I also regret that I didn’t photograph it. Also the Greek actress, Irene Pappas, came for lunch.

And the photographer Gordon Parks did his first [film] directing at the time from his book The Learning Tree about his childhood in Kansas. He invited us to look at the rough print [at] Warner Studios. And Parks wanted to direct Malcolm X. This project had gold attached to it, and everybody wanted a piece of it.

Baldwin would come home at night quite exhausted after dealing with studio executives. One night he came in and said, “You won’t believe what happened today ... The studio executive wants Charlton Heston to play Malcolm X. He said with a little makeup job we can make him into Malcolm.” He couldn’t believe it, but that’s the mentality he was up against. We both considered it a joke that the man who split the Red Sea would play Malcolm.

Shortly after, he left [the States]. The film was never finished as a feature film. Arnold Perl stayed on as screenwriter and convinced them to turn it into a full-length documentary. I was one of the researchers so I went to Tunisia and found some film of Malcolm X when he was doing a pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia, and I also went to Paris and found some film. It was finished in 1973. It opened in about 200 theaters and a week later Warner pulled it and it disappeared. I heard all kinds of conspiracy theories like pressure from the government.

When did you make your film on Baldwin, In Another Country?

I graduated in 1968, and all of these new documentary films were coming out by the Maysles Brothers, Pennebaker, Wiseman and people of that sort. They didn’t have the usual voiceover narration. I thought Baldwin would be the ideal subject for a film like this if you just let him talk. All you had to do was point a camera at him and you’d get a fabulous film.

With this idea, I went to a film company and they said they would finance it. I got very excited and went back to Turkey in 1970.

His agent told Jimmy not to do it because this would be a waste of money and time, and he convinced me not to do it. But I still wanted to do something on Baldwin. He was so animated, so intelligent, so articulate. Something had to be done to preserve this bundle of energy and intelligence.

Baldwin rented a house in the middle of Istanbul. I said let’s do [the film] here. A good friend who did feature films had his own camera. The very first morning, the maid answered the door and I asked where was Mr. Baldwin, and she said he’s sleeping. I said to the cameraman, “Let’s go into the bedroom.” We barged into his room as he was waking.

We finished filming, and I couldn’t take it out because Turkey had very strict rules about exporting film. You had to go through a censor board and government agencies. The film sat in my family’s apartment [and] my clever uncle found a way to get this film out. It came to my apartment in New York City.

The film was finished and I rented a classy theater in New York City. The place was full, standing room only. I showed the film, which was only 12 minutes. It was very well received.

One of the audience members was Maya Angelou, who came with Gloria, Baldwin’s sister. Gloria was always embarrassed by Baldwin’s sexual preference. I have a feeling they may have been embarrassed by the opening scenes with Baldwin in his underwear. They passed me by without saying anything.

Baldwin never saw it. He was in France. In the last few years, there’s been an incredible amount of demand for the film. I have shown it and talked at universities [such as] the University of Michigan, in Minnesota, and at New York University. I’m very proud of it and it’s wonderful stuff.

I’m thinking about doing a part two of Baldwin with interviews I didn’t use. He was very disturbed at that time by an article in Life about white mothers in Alabama spitting on little black children, and I asked him about it. He asked, “How can a mother do this to somebody else’s child?”

I didn’t see Baldwin after that, which is a shame.

What else should people know about Baldwin, especially younger people who may not be familiar with his work?

Many people ask me this question. I always tell them what directed his life was love. He basically wanted people of all colors and races and nationalities to live together, to understand the humanity in all of us. To me, that’s what James Baldwin represents -- that we shouldn’t divide people into categories according these specifications. What he wanted was synthesis of races, black and white. Everybody should live together and love one another.

Do you have any concluding comments on James Baldwin?

When I came to Yale, people who saw my pictures said this guy is passé. He was famous in the fifties and sixties. And they asked how come you show him happy and smiling in these pictures. We thought he was angry and solemn. In real life, the man loved to laugh. But if you said something offensive about race, he would cringe and become ferocious.

And he was very eloquent and very intelligent and very well read. That was amazing. When I was living in his household for months in L.A., he would go to his room after dinner and write. The thing that amazed me is that he talked about conditions in Zambia or the economics in England, and I asked myself when does he have time to read these things. That was before the information age and the Internet. Where did he find this information and when did he read these things to have an informed opinion?