The American Roots of Neoliberalism

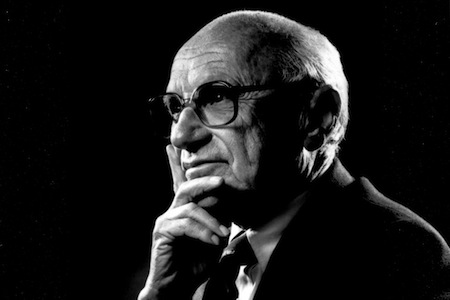

Portrait of Milton Friedman. Credit: The Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice.

The word “neoliberalism” -- the ideology of free markets, deregulation and limited government -- is easily lost in translation from the European to the American context. In part this is a reflection of the different meanings of liberalism in Europe and the United States. But it also highlights a gap in historical understanding, which is only just beginning to be filled.

The word “neoliberalism” -- the ideology of free markets, deregulation and limited government -- is easily lost in translation from the European to the American context. In part this is a reflection of the different meanings of liberalism in Europe and the United States. But it also highlights a gap in historical understanding, which is only just beginning to be filled.

In Europe (and much of the wider world), neoliberalism is often seen as an American model of unrestrained market capitalism that has wrought havoc both on the developing world through the structural adjustment policies of the “Washington Consensus” and, most recently, by causing the financial crisis that brought the world economy to its knees in 2008. In the United States, by contrast, mention of the word often raises a quizzical glance, an assumption that it has something to do with Bill Clinton’s New Democrats who claimed to reform liberalism in the late 1980s and 1990s or prompts a conversation about the rights or wrongs of the worldview of Paul Wolfowitz, the archetypal neo-conservative. Free markets are anyway viewed in the United States by advocates as being as American as apple pie and little attention is paid to the trans-Atlantic influences that have led to a distinctively neoliberal conception of free enterprise taking hold among American policymakers.

These misconceptions are unhelpful because they obscure important elements of recent transatlantic history. It is of course true that American historians, since Alan Brinkley’s famous 1994 essay, "The Problem of American Conservatism," have opened up in all sorts of fruitful directions the study of the rightward turn taken in the United States since the 1960s. But it remains a strange feature of the debate, perhaps another hangover of oft-noted American exceptionalism, that the history of the set of ideas that much of the rest of the world most associates with the American model of capitalism, neoliberalism, is only imperfectly understood in the United States itself. In my book, Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics, recently published by Princeton University Press, I trace the history of neoliberalism, which I argue obtained a distinctively American inflection in the postwar period.

Neoliberalism first emerged in the interwar period, primarily in Austria, Germany, France and the United Kingdom, among thinkers and economists, who saw a need to reform liberalism. Writers like Friedrich Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, Walter Eucken, Wilhelm Röpke, Raymond Aron and Jacques Rueff thought that the “nightwatchman state” of laissez faire, exemplified by nineteenth century Britain, had proved inadequate for the problems of the early twentieth century. They saw a threat to individual freedom in the defeat of liberal politics by the totalitarianism of fascism and communism. Neoliberals also saw the activist and interventionist liberalism of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, along with that of the British Liberal governments of Herbert Henry Asquith and David Lloyd George, as a perversion of liberalism.

These primarily European neoliberals (though there were some Americans like Chicago economist Henry Simons) sought a reformulation of liberalism that would recover the classical liberal focus on individual liberty. Neo-liberalism was therefore an attempt to find a new middle way between what the neoliberals saw as failed laissez faire on the one hand and a new form of liberalism dominated by economic planning on the other that would form the basis of a counterattack against totalitarian impulses of left and right. Famously, Hayek became the chief proponent of this early neoliberal movement in his book The Road to Serfdom (1944). The defining features of the movement were a focus on anti-trust and fostering the conditions for a competitive economy and a concomitant acceptance of the need for a social safety net.

In the 1940s Hayek also developed an intellectual strategy for political influence, which he outlined in a seminal article entitled "The Intellectuals and Socialism" (1949). The central idea was that the neoliberals needed to learn from the success of the liberal left in Britain and the United States in the early twentieth century. Like the Fabian Society in Britain and the Brookings Institution in the United States the task was to influence intellectual opinion, which would force a change in the public debate over the long term. For Hayek, intellectuals encompassed all educated opinion from journalists, scientists and civil servants to experts in particular fields. The best way to attain political success would be to establish thinktanks to promote the neoliberal agenda. To this end, Hayek had already founded the Mont Pelerin Society (MPS), whose first meeting was held in Switzerland in 1947.

In retrospect, the first meeting of the MPS can be seen as a turning point in the history of neoliberalism. The meeting was attended by a number of young American scholars, Milton Friedman, George Stigler and James Buchanan, all of whom would profoundly influence the development of neoliberal ideas in the postwar period and shift the centre of gravity of the movement from Europe to the United States.

American neoliberalism took on a more radical character than its European precursors as Hayek’s intellectual strategy came to fruition. In the 1950s and 1960s, both Hayek, who had moved the University of Chicago in 1950, and Friedman, who was already based there, became the leading hubs of a trans-Atlantic network of thinktanks and business-funded foundations such as the American Enterprise Institute (founded in 1943), the Foundation for Economic Education (1946), the William Volker Fund (1932, run by Harold Luhnow after 1944), the Earhart Foundation (1929) and the Institute for Humane Studies (1961). These organisations and others were joined by a second wave in the 1970s with the establishment of the Heritage Foundation (1973), the Cato Institute (1977), the Manhattan Institute (1980) and the Charles Koch Foundation (1980).

Friedman and Stigler became the leaders of the "Chicago School" of economics and Buchanan and his colleague Gordon Tullock established the "Virginia School" of political economy. Both "schools" sought to introduce market-based analysis to new areas. Friedman reformulated macroeconomics around a revival of the quantity theory of money. Stigler critiqued the dominant approaches to economic regulation whereby the regulated too often captures the regulator. Buchanan and Tullock applied the model of the individual pursuing his rational self-interest in the market to the realms of politics and government. Another Chicago economist and fellow Nobel prizewinner Gary Becker applied Chicago market-based theories to crime, the family, health and education. The process became known as economics imperialism.

At the same time as this expansion of market ideas was taking place the original emphases of neoliberal thought were changing. A crucial project, the Free Market Study, was undertaken in the 1950s at Chicago, led by Aaron Director, Friedman’s brother-in-law. This study began to reformulate key neoliberal assumptions. The problem of monopoly was no longer seen as one of market failure but as one of government failure. In other words, government intervention, by favouring particular players, distorted the effective operations of the market. Large corporations had built into them self-correcting mechanisms and incentive structures that replicated the conditions of competition. Instead of market failures, the real problem of monopoly was now revealed to be, in the Chicago view, the distorting role played by labor unions. Lastly, Milton Friedman, in his famous book Capitalism and Freedom (1962) and his weekly Newsweek columns substituted the supposedly more efficient market mechanism for the welfare state in a range of social policy spheres.

This moment when neoliberalism becomes a distinctively American idea incubated in interwar Europe but refined in Chicago also marks its political breakthrough in both the United States and in Britain. To be sure for such an advance to occur required the perceived failings of liberalism in general and of neo-Keynesian demand management in particular, a policy approach that was proving powerless in the face of the novel problem of the 1970s: ‘stagflation’. But there is no doubt that the change in neoliberalism from its early European origins to those in postwar America represented a radical clarification that sharpened the political message and made it more easily digestible. Key tenets of the Chicago world-view would become the centrepieces of the new political settlement after 1975.

At first, politicians of the left introduced neoliberal policies, such as Friedman’s monetarism and Stigler’s deregulation. For example, Carter appointed Paul Volcker to the Fed and introduced legislation to deregulate airlines, transport and finance. The Labour Government of James Callaghan in Britain introduced similar changes. But afterwards a more wholesale philosophy of free markets took hold under Reagan and Thatcher. The radical nature of American neoliberalism was made clear in the ‘trickle-down’ economics supported by Reagan’s leading economic advisers and influences, Arthur Laffer, Martin Feldstein and Milton Friedman. Clinton, Larry Summers and Robert Rubin left this radical free market ideology substantially un-tampered with. Certainly, in welfare reform, the pursuit of ‘flexible labour markets’ and the repeal of Glass-Steagall, it was possible to see the entrenchment of key neoliberal policy prescriptions.

The legacies of American neoliberalism -- guileless faith in markets and overweening hatred of government and public expenditure -- still dominate the Republican Party today in the perpetual crises over debt ceilings, fiscal cliffs and sequesters. But they also influence the agendas of President Obama and his Treasury team too. After a brief Keynesian resurgence in early 2009, the dominant economic agenda is once again an awkward mix of Hayekian deficit reduction and sub-Friedmanite monetary stimulus. Only by examining this complicated and layered history of neoliberalism and its political breakthrough can some sense be made of the economic predicament that we find ourselves in today.