California's Dark History of Eugenics and Compulsory Sterilization

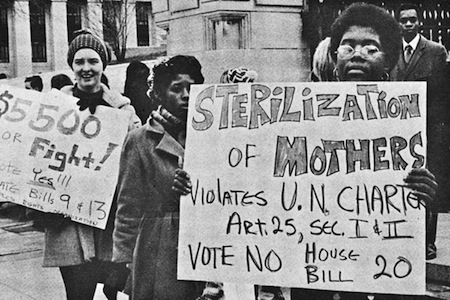

Anti-sterilization protest in Louisville, KY, in 1971. Credit: Southern Conference Educational Fund.

Cross-posted from GoodToGo.

The recent revelation that 148 female prisoners in two California institutions were sterilized between 2006 and 2010 is another example of the state’s long history of reproductive injustice and the ongoing legacy of eugenics. The abuse took place in violation of state and federal laws, and with stunning disregard for patient autonomy and established protocols of informed consent.

The recent revelation that 148 female prisoners in two California institutions were sterilized between 2006 and 2010 is another example of the state’s long history of reproductive injustice and the ongoing legacy of eugenics. The abuse took place in violation of state and federal laws, and with stunning disregard for patient autonomy and established protocols of informed consent.

In the past, sterilization of vulnerable populations in the name of “human betterment” was carried out with legal authority and the backing of political elites. What current and past practices share is the assumption that some women by virtue of their class position, sexual behavior, or ethnic identity are socially unfit to reproduce.

The unauthorized sterilization of women in prison was facilitated, as the federal courts have recognized, by a combination of inhumane practices, overcrowding, bureaucratic inconsistencies, and medical neglect. From the torturous conditions in the state’s Security Housing Units, to the exposure of prisoners to life-threatening illnesses, and the trampling of women prisoners’ reproductive rights, California rivals many Southern states in penal cruelty.

It’s a heartening sign that many groups, including the state’s legislative women’s caucus, are expressing outrage and asking how these violations of rights could take place in the twenty-first century. Much of the answer can be found in the twentieth century.

In 1909, California passed the country’s third sterilization law, authorizing reproductive surgeries of patients committed to state institutions for the “feebleminded” and “insane” that were deemed suffering from a “mental disease which may have been inherited and is likely to be transmitted to descendants.” Based on this eugenic logic, 20,000 patients in more than ten institutions were sterilized in California from 1909 to 1979. Worried about charges of “cruel and unusual punishment,” legislators attached significant provisos to sterilization in state prisons. Despite these restrictions, about 600 men received vasectomies at San Quentin in the 1930s when the superintendent flaunted the law.

Those sterilized included people with conditions we would classify today as psychiatric disorders or intellectual disabilities, as well as individuals with limited educational and economic resources, including thousands of “antisocial” minors. Initially, men in psychiatric homes were targeted for sterilization; however, eugenicists mostly targeted “feeble-minded” and “promiscuous” women, including those who had one or more children “out of wedlock.”

Moreover, there was a discernible racial bias in the state’s sterilization and eugenics programs. Preliminary research on 15,000 sterilization orders in institutions (conducted by Stern and colleagues) suggests that Spanish-surnamed patients, predominantly of Mexican origins, were sterilized at rates ranging from 20 to 30 percent from 1922 to 1952, far surpassing their proportion of the general population. In Miroslava Chávez-García’s recent book, she shows, through exhaustively researched stories of youth of color who were institutionalized, and in some cases sterilized, in state institutions, how eugenic racism harmed California’s youngest generation in patterns all too reminiscent of incarceration and imprisonment today.

California was the most zealous sterilizer, carrying out one-third of the approximately 60,000 operations performed in the thirty-two states that passed eugenic sterilization laws from 1907 to 1937. Furthermore, unlike many other states, where sterilization laws were challenged in the courts, in California the sterilization law remained on the books for seventy years.

Although it was scaled back in the early 1950s, the law was not repealed until 1979, in the context of another chapter of sterilization abuse. This time, about 140 women, mainly of Mexican origin, were sterilized without consent at USC/Los Angeles County hospital. From the late 1960s to the early 1970s, the leading obstetrician at this hospital maintained strong convictions about the need for population control, which he applied to women during and immediately after labor by coercing them into tubal ligations. Sometimes women signed a consent form under duress, other times they were not offered any consent form, or falsely told that their husbands had already signed the form.

Working with the Los Angeles Center for Law and Justice, in 1978 ten women filed a lawsuit against USC/LA County hospital and the implicated obstetrician. Although they lost, this case and parallel lawsuits filed by women of color around the country, resulted in new federal guidelines for sterilization, including a 72-hour waiting period and informed consent requirements.

Many of the stereotypes that fueled twentieth-century sterilization abuse remain in vogue today. Dr. James Heinrich, who performed tubal ligations of women in prisons, stated that this practice saved the state money because his involuntary clients were likely to have "unwanted children as they procreated more.” Such a callous attitude could have been uttered by superintendents in the 1930s, who worried about the economic burden of “defectives,” or by the obstetrician at USC/LA County who purportedly spoke to his staff about “how low we can cut the birth rate of the Negro and Mexican populations in Los Angeles County.”

It is time to break the cycle of reproductive injustice in California, and to challenge the continuing potency of eugenic rationales of cost-saving and societal betterment through nonconsensual and unauthorized sterilizations. The twenty-first century calls for a new era of human rights, institutional oversight, and the protection of vulnerable populations.