Why I Believe Meriwether Lewis Was Assassinated

General James Wilkinson, commanding general of the U. S. Army, was known as Spanish Agent #13 in the Spanish records, which reveal Wilkinson received $26,000 in payments during 17871804. These payments were the focus of several congressional investigations and military courts. Though the charges were never proven during the general’s lifetime, historian Frederick Jackson Turner called Wilkinson, “the most consummate artist in treason the nation has ever produced.”

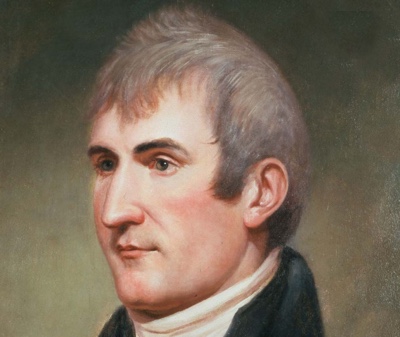

In my new book I argue that Wilkinson’s

long list of crimes includes the assassination of Meriwether Lewis,

the famed explorer and Governor of Louisiana Territory.

In my new book I argue that Wilkinson’s

long list of crimes includes the assassination of Meriwether Lewis,

the famed explorer and Governor of Louisiana Territory.

The evidence for Wilkinson assassinating Lewis consists of four parts: (1) the general’s reputation as an assassin; (2) proof that the suicide account of Lewis’s death is a lie; (3) A cover-up produced by Wilkinson, known as the “Russell Statement”; (4) his involvement with liberating Mexico after Lewis’s death.

(1) The general’s reputation as an assassin

Accusations of General Wilkinson being an assassin are found in three places in the historic record. General Anthony Wayne, commanding general of the U. S. Army called Wilkinson “that vile assassin” in a letter to Secretary of War Henry Dearborn in 1795. Senator Humphrey Marshall of Kentucky, in his 1812 History of Kentucky, accused Wilkinson of assassinating officers Hardin and Trueman and attempting to assassinate himself, Marshall, in 1792. Major Gilbert C. Russell testified under oath at Wilkinson’s court-martial on November 5, 1811 that Major Seth Hunt told him Wilkinson had tried to assassinate him (Hunt) in 1806.

In my book I accuse Wilkinson of arranging the assassination of Wayne by arsenic poisoning. General Wayne died of “stomach gout” on December 15, 1796 on his way to Philadelphia to answer charges by his second in command, Wilkinson. Only one general would be needed in the peacetime army, and Wayne’s death automatically gave command of the army to Wilkinson.

(2) Proof that the suicide account of Lewis’s death is a lie

Governor Meriwether Lewis was on his way from St. Louis to Washington in September, 1809 to protest the federal government’s refusal to reimburse him for expenses. After his death, the government reimbursed his estate $5, 267. Lewis died under mysterious circumstances in an isolated traveler’s inn called Grinder’s Stand on the Natchez Trace on October 11, 1809.

The account of his suicide is contained in a letter written to President Jefferson on October 18th. The letter was supposedly from Indian Agent James Neelly, who was serving as Lewis’s escort on the Natchez Trace. The letter itself was written in Nashville, Tennessee by Captain John Brahan, who wrote an almost identical letter to the President. The supposed letter from Neelly in Brahan’s handwriting was signed with a forged signature.

Coincidentally, on the same day, October 18, Neelly was writing a letter to the Secretary of War from his Indian Agency near Tupelo, Mississippi. The whereabouts of James Neelly during the last days of Lewis’s life are the subject of new evidence discovered by Tennessee attorney Tony Turnbow. Neelly claimed he was looking for “two lost horses,” and wasn’t present at the scene of Lewis’s death at Grinder’s Stand on October 11. Turnbow discovered instead that Neelly was being sued for debt in a Franklin, Tennessee courtroom on the day Lewis died. I propose that Neelly was recruited at the last minute to participate in a conspiracy to assassinate Lewis, and had to arrange the assassination to fit his long-standing commitment to appear in court.

Governor Lewis was traveling by boat from St. Louis to New Orleans. When he arrived at Fort Pickering (Memphis) he changed his plans and decided to travel overland on the Natchez Trace. Major Gilbert C. Russell, the commander of the fort, wrote two letters to President Jefferson concerning the last days of Lewis’s life. The contents of these letters contradict the so-called “Russell Statement” produced during General Wilkinson’s court-martial in 1811.

Lewis was buried in the yard of the inn where he died. His death was not investigated. In 1848, the state of Tennessee established a commission to erect a monument at his gravesite. The commission opened his grave and in their final report wrote: “It seems to be more probable that he died at the hands of an assassin.”

(3) A cover-up produced by Wilkinson: The “Russell Statement”

In 1962 historian Donald Jackson published the so-called “Russell Statement” in his Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents. The statement was examined by two hand- writing experts during the coroner’s inquest held in Hohenwald, Tennessee in 1996. They testified it was neither written nor signed by Major Russell. Dated November 26, 1811, the statement was written in the distinctive handwriting of a scribe whom General Wilkinson used on other occasions. General Wilkinson was undergoing a court-martial in Frederick Town, Maryland to clear his name of being a Spanish agent and mismanaging the army in New Orleans. He was acquitted of all charges.

The Russell Statement says that Lewis made two attempts to kill himself while on the boat. (Major Russell made no mention of this in his letters to the president.) It concludes with a chilling description of Lewis’s suicide: “. . . he lay down and died with the declaration to the Boy that he had killed himself to deprive his enemies of the pleasure and honor of doing it.”

The interesting question is why would General Wilkinson--in the midst of a court-martial--create a forgery concerning Lewis’s suicide? The answer appears to be that Russell had testified under oath a few weeks earlier that Wilkinson had tried to assassinate Major Hunt. Records show Major Russell went AWOL during the month of December and reappeared after Wilkinson’s acquittal. A few weeks later, Russell was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel.

(4) Wilkinson’s involvement with liberating Mexico after Lewis’s death

What was Wilkinson’s motive for killing Lewis? I propose the motive was to prevent Lewis from bringing information to Washington regarding crooked land deals involving Wilkinson and John Smith T, a mine operator in the lead mine district south of St. Louis. Wilkinson had been the first governor of Upper Louisiana in 1805-06. Lewis was bringing lead mine records to Washington. After his death, his papers were inventoried and bundled and entrusted to the care of Thomas Freeman, a Wilkinson associate. They arrived in Washington in total disorder.

Wilkinson and his distant relatives, the Smith brothers, were conspiring to participate in Father Hildago’s revolution for Mexican independence in 1810. The silver mines of Mexico, which produced the world’s hard currency, were the object of numerous foreign and domestic conspiracies. A few weeks after Lewis’s death became known in St. Louis, Reuben Smith set out with a small advance party to Sante Fe. They were captured by the Spanish and imprisoned for two years. While imprisoned they witnessed Father Hildago’s execution. Upon their release they joined the Guttierez-Magee filibuster expedition into Spanish Texas in 1812-13. Magee was Wilkinson’s protégé and Wilkinson’s son served in this expedition. Wilkinson died in Mexico City in 1825 while waiting to receive a Texas land grant.

Wilkinson had a history of assassinating, or attempting to assassinate, people who were his rivals and possessed incriminating information that could jeopardize his career. Meriwether Lewis was a man “of undaunted courage” who bravely stood up to him.