What We Can Learn from Fake News

Fake news has both producers and consumers. Stories like the one about the Pope endorsing Donald Trump for president are eye catching, but fake news can really only generate much power when a lot of people believe it. Without that, it is just so much sputtering, and can even backfire on the perpetrators by smearing them with a reputation for dishonesty or for being just plain crazy.

The Franklin Roosevelt administration kept a file labeled “Below the Belt” full of media slurs against the president. The fakery was actually an asset because it encouraged people to associate his opponents with crackpot ideas. Charges that he was orchestrating international conspiracies actually provided political cover in the late 1930s while President Roosevelt took steps in opposition to Nazi Germany.

The

political problem with fakery is not its lies, but the capacity for

that fakery to seem likely. News accounts, true or false, are

embedded in story lines, mental frameworks for organizing those

facts. Public falsehoods are not news, but the current media

environment has new capacities to generate and disseminate more

information than ever, with fewer filters sorting for plausibility.

And the capacity to narrowcast to particular audiences, with stories

of any degree of truth, increases the chance that people will learn

what they already think they know.

The

political problem with fakery is not its lies, but the capacity for

that fakery to seem likely. News accounts, true or false, are

embedded in story lines, mental frameworks for organizing those

facts. Public falsehoods are not news, but the current media

environment has new capacities to generate and disseminate more

information than ever, with fewer filters sorting for plausibility.

And the capacity to narrowcast to particular audiences, with stories

of any degree of truth, increases the chance that people will learn

what they already think they know.

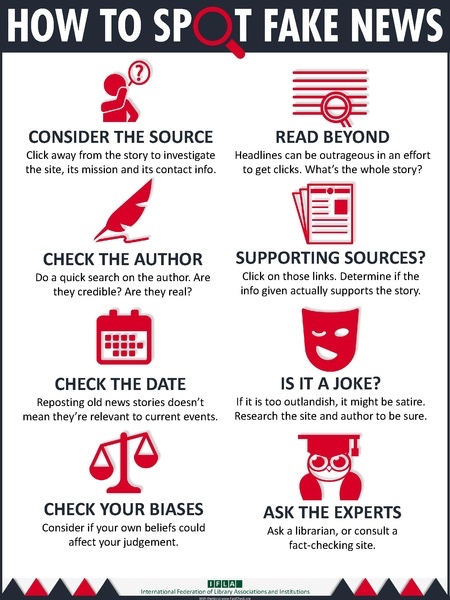

In our current arms race over knowledge claims, increased fake news embedded in narratives of likely stories, faces fact checking by Politifact.com, Snopes.com, mainstream news organizations, and even Factitious, a game that mixes fun with links to sites “known to be trustworthy.” These authoritative evaluators seem to offer a slam-dunk solution. Politifact even allows for degrees of accuracy with ratings of claims from “True” to “Mostly False” to “Pants on Fire” (as in the children’s ditty, “liar, liar, pants on fire”). Problem solved? Hardly, because fact checking does not reach into the world of likely stories.

Psychology sheds light on human impulses for selecting some facts in the build up to particular story lines. Even in simple situations, there is much more happening in any one person’s whole experience than can be perceived; countless sights and sounds, and complicating memories and anticipations make each experience superabundant. The perennial intricacies of human experience have been amplified, especially since the late nineteenth century, by abundant technological changes and more diversity of social interaction. Through these thickets psychologist William James is a good guide.

James observed that the mind selectively attends to some portions of experience while ignoring others based on each person’s particular temperament and interests and the purposes at hand. And he extended his insights about these psychological dynamics into an explanation about how whole points of view are formed: each person’s “sentiment of rationality,” also shaped by interests and purposes, establishes orienting ways of thinking that let us feel “at home” with our own assumptions and alienated from those of others. Assumptions serve as magnets for attraction or repulsion when encountering new information and interpretations, and serve as the ground floor of ideological commitments.

The impulses for selective construction of ideologies have gained support from the information revolution. To those with enough resources to afford the technology, facts and interpretations of them in uncountable variety are available instantly in the palms of our hands. Mainstream media sources compete with all others, each with their own selection of information and interpretations. And in this market dynamic, each person serves as an independent information gatekeeper, free to choose belief in any particular news item based on the story that seems most likely to be true to that person, whether it is actually true or false.

The reduced authoritative credibility of mainstream media has been compounded by the emergence of many sources of information that not only compete, with their own angles of vision on the news, but also explicitly identify the mainstream purveyors of news as inherently biased. Major news outlets receive criticism from the left wing as mouthpieces of the corporations that own them, and from the right as perpetrators of multicultural or socialist agendas. To date, the right-wing critics have gained much more influence with large audiences and with many politicians made cautious by their pronouncements.

Popular conservative talk-show host Rush Limbaugh spends at least as much time excoriating the mainstream media for “hating America” as he does in criticism of liberal politicians. The enormous pools of information provide forceful speakers such as Mr. Limbaugh with plenty of choices. He selects the facts that fit his assumptions, and then, using his critics’ arguments against them, he calls any other facts “fake news,” a broad brush reinforced by occasional scandals such as Jayson Blair’s 2003 plagiarism and made-up stories on the front pages of the New York Times. So even fact checking is readily dismissed by listeners to The Rush Limbaugh Show if the source of the checking is in the “liberal media.”

The net result is that even authoritative news outlets have lost much of their credibility for large chunks of the population, even when their work is outstanding. This undercuts not only the ability for fact checking to have substantial impact, but also the readiness of citizens to listen to different interpretations.

To those who believe inaccurate or exaggerated news reports, attacks on those stories look like equal and opposite reactions to Trump’s aggressive rhetoric, delivered by intellectual elitists no less. Many who voted for him show little interest in fact checking; as one supporter of the president explained, “it’s not what he says, but what he represents.” Accurate news is important, but so too are the stories the information represents.

False information gains strength from its roots in stories that make sense to a lot of people; mow down the latest false facts and more will soon sprout until we address those stories themselves—and the reasons people believe them. This intellectual engagement with popular ways of knowing will improved democratic practice, and the increased awareness offers the best preparation for the next election.

Hillary Clinton presented an iconic portrait of liberal contempt for Trump supporters when she slapped them in September 2016 for belonging in a “basket of deplorables.” This was a vital message about the intolerance and even militarism of some of his supporters. Her whole statement was that this appeal through fear and anger was deplorable, but that the “other basket” of his supporters are “people who feel that the government … and the economy … has let them down.” Her insult invited a Gotcha response, magnifying Trump support (shop now for “I’m a Deplorable” tee shirts and mugs), even as her commentary about his populist appeal really deserves political attention from all parties, but continues to be largely overlooked.

Disagreement over policies without hostility to the people holding them is a practical expression of the classic posture of religious leaders wise enough to hate the sin but love the sinner.

In a season of political ballyhoo, attention to the shock of fake news has served to distract from the importance of the stories surrounding those reports. Empathetic listening to stories of all stripes is not a last word for solving our political tensions, but it can be a first step toward more effective political action. You don’t have to stop fighting against the policies to which these stories point; you might even pick up some new ideas about your own ideology and ways to present it. A better democracy awaits when you take a look at the other side, and try listening to the false facts for clues they provide about the stories that make the fakery seem true.