The American Tourist in Paris: A Retrospective

Screenshot from Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. Image courtesy of Imdb.com.

For many Americans, spending time in Paris is a chance to enjoy the same delights, copious amounts of champagne and dancing to jazz at the all-night parties in the cafes and clubs of Montparnasse, that some of the nation’s greatest writers did during the années follies of the 1920s. Films like Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris glamorize the idea of this ‘faux bohemian’ life style in which “struggling” American writers, fleeing from the puritanical restrictions at home, were able to liberate themselves and indulge in all the pleasures Paris had to offer. This idea of a morally liberated city where one can indulge in all the pleasures life has to offer remains one of the many reasons Americans continue to flock to Paris on their vacations, be it for a few weeks, months, or years.

The presence of Americans in Paris stretches back to the days of the American Revolution, when diplomats and their families visited the fashionable salons of the Parisian nobility and haute bourgeois. Throughout the 19th century this trend continued with the wealthy members of American society taking in the sights, arts, and fashions of the city. The advent of easier, cheaper travel via steamship led to a broader range of upper middle-class tourists coming to enjoy the pleasures of the city throughout the Belle Époque era at the end of the century. The haute-couture houses in the fashionable 2nd arrondissement became a hub for wealthy American women, while the decidedly less reputable maisons closes/maisons tolérées became a must-see for many young American men.

Paris’s reputation as a city of pleasures carried over into the First World War, with many American troops seeking and sharing information about where to spend an evening or two. After the Armistice was signed and the U.S. military no longer curtailed periods of leave, these evening galivants through the city’s less reputable locations dramatically increased (as did the reported cases of various venereal diseases). The presence of large numbers of American soldiers enjoying their leave in Paris heightened long-present fears among French troops on the front about the infidelity of women on the home front.

While French troops might have resented the presence of Americans in Paris, civilians appreciated the energy (and money) the troops brought to the war-weary city. This was particularly true among those working in the luxury goods industries, as the well-paid American looking for souvenirs to bring home helped to ease their financial burdens created by wartime restrictions. The Parisian love affair with Americans in the immediate post-war years remained strong as President Woodrow Wilson and his Fourteen points became a symbol for peace and hope for the future of the world.

However, following the refusal of the U.S. Senate to ratify the Versailles Treaty and the joint security accords between France and U.S. in 1920, relations between the two nations soured quickly. Combined with these diplomatic tensions, the importation of Americanized mass marketing, business practices, and five-and-dime stores were viewed with suspicion as they appeared to undercut traditional French values and business practices. Fears of the Americanization of French life and culture grew exponentially during 1920s, and remains a source of concern for many French people today.

The importation of American culture occurred alongside a massive increase in American tourists. The 1920s saw the numbers of American tourists increase from 15,000 to over 400,000 annually and the number of expats living in the city jumped from 8,000 to nearly 23,000 by 1923. The behavior of these American tourists and expats throughout the 1920s did nothing to ease the fears and tensions created during the First World War. The depressed value of the franc following the war made the luxuries associated with the “good life” easily attainable for the Americans living in and visiting the city, while for native Parisians it made basic household necessities difficult to afford. As Mary McAuliffe discusses in her book When Paris Sizzled: The 1920s Paris of Hemingway, Chanel, Cocteau, Cole Porter, Josephine Baker, and Their Friends, many Parisians viewed the ways in which Americans flaunted their wealth in fashion and extravagant soirées as extremely vulgar, and the avant-garde art movement they often patronized was considered by many as a foreign intrusion and an undesirable addition to the French artistic repertoire. The difficulties of getting a table at the hottest clubs and cafes in Montparnasse due to the constant presence of Americans was a cause of annoyance among Parisians; the unpaid bills and broken/stolen furniture did nothing to endear Americans to the proprietors of the establishments.

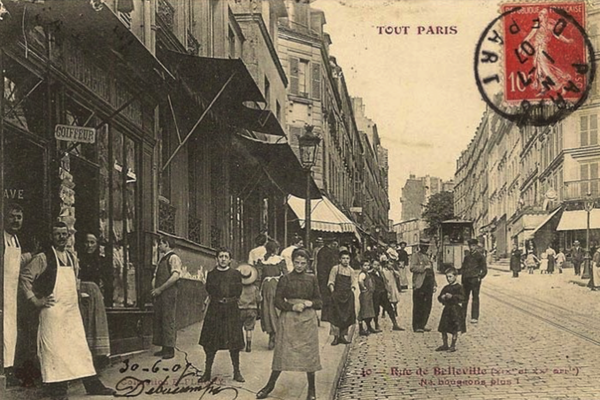

Life for most Parisians during the 1920s was much less glamourous than that of the many American expats. Image courtesy of Luc Sante (lucsante.com)

Combined extravagant displays of wealth and general disregard for local property, one of the main areas of contention between the Americans and Parisians was the overtly racist attitudes Americans had towards members of the black community. Paris in the 1920s was enraptured with all things associated with African Art and African-American culture (jazz, the Charleston, Josephine Baker, etc). Those Parisians who partook in this négrophilie considered themselves to be the epitome of the modern and fashionable world. Although extremely problematic in that it sexualized and fetishized black culture (see Jennifer Anne Boittin’s Colonial Metropolis: The Urban Grounds of Anti-Imperialism and Feminism in Interwar Paris), the Parisian négrophilie provided opportunities unavailable in the United States for African-Americans, particularly for performers, with Josephine Baker being the best example of this phenomenon. White Americans, however, were often horrified at the ways Parisians openly appreciated and enjoyed the imported black culture. They went so far as to frequently, and at times violently, demand that club and restaurant owners expel black performers and patrons. Things eventually got so bad that the French Minister of Foreign Affairs had to issue a statement:

“some foreign tourists, forgetting that they are our guests and that, consequently, they should respect our customs and our laws, have recently, on numerous occasions, violently.... demanded [black persons'] expulsion in offensive terms. If this continued, sanctions will be taken.”

Sanctions were not taken. However, the onset of the Great Depression forced many Americans to pack their bags and head home as the good life, or any sort of life, in Paris was no longer affordable. The return of American troops during the Second World War and the boom period which followed the end of the war brought Americans back to Paris. These tourists once again indulged in the delights of the city, and throughout the second half of the 20thcentury helped to maintain Paris’s status as the home of fashion, art, and fine dining.

Today Americans remain one of largest groups of international visitors to Paris. With over 2 million Americansannually descending upon the city, it is hard for locals to ignore the contributions they make to the local and national economy. Relations between Parisians and American tourists are much less tense today than they were throughout the 1920s, with American tourists presenting a constantsource of amusement for Parisian inhabitants, particularly when it comes to their fashion choices (see below). Their large numbers however continue to contribute to the numerous tourist-centric problems facing the city. While crowded streets and metros are aggravating during weekday commutes, the inundation of short-term rentals like Airbnb has caused an already tight and expensive housing market to become even tighter and more expensive, forcing many Parisians to leave the city for good and leaving the tourist-centric arrondissements surrounding the Louvre in particular bereft of tax payers and children to fill classrooms. Although no longer breaking furniture, running out on checks, and throwing racist fits about the evening’s entertainment, Americans remain an integral part of Paris’s continued debates over the benefits and detriments of being one of the world’s largest tourists destinations.

The signature “white socks with shorts” look of many American tourists is a constant source of amusement for Parisians. Image courtesy of The Telegraph.