Reconsidering Journalist and Gay Activist Randy Shilts

Twenty-five years ago, Randy Shilts went to his death a conflicted man. He talked openly about the frustration of his life being finished without being complete. Beyond the obvious pain, panic or dread he must have felt as he succumbed to AIDS-related health complications, he knew there was so much more to do, but he was not going to be around to do any of it.

In many senses, he had not resolved personally the dissonance that seemed ever beneath the surface of just what his role was – or who he was supposed to be. He publicly clung to claims of being an objective journalist – “What I have to offer the world is facts and information,” he told Steve Kroft and the nation during one of his last interviews (aired on the CBS franchise 60 Minutes the week he died in February 1994). A closer examination of his life and work reveals, however, that it was not just facts and information that he sought to impart as an objective journalist, but that he sought to fully inhabit the role that Walter Lippmann long ago described as the “place” for many journalists. He fully embraced the idea that our society and culture were in need of an interpretation a trained journalist (and critical thinker) could provide, but moreover, the need to shine the light of media in the right places and set the agenda of what was important, and what was not.

Shilts’s light-shining would be what could win him fierce critics, particularly as he sought to transport himself from just a “gay journalist” to “journalist who happens to be gay.” As one of the nation’s very first openly gay journalists at a major daily newspaper, The San Francisco Chronicle, he sought to distinguish himself not only as a legitimate journalist, but also as a representative of the welcomed homosexual in a vehemently heterocentric world. Doing so meant he quickly personified the clichéd role of the journalist more skilled at making enemies than friends, who instead worried more about making a point. For Shilts, that is what journalism was for, to move society and the people in it to a new place, to a new understanding of or relationships with one another. Facts and information could do that, but Shilts understood how to focus those facts, right down to when a story appeared; he openly acknowledged that he timed stories that raised the frightening prospect of HIV and AIDS for Friday editions of The Chronicle to put some fear into his fellow gay tribe members as a weekend free for partying approached.

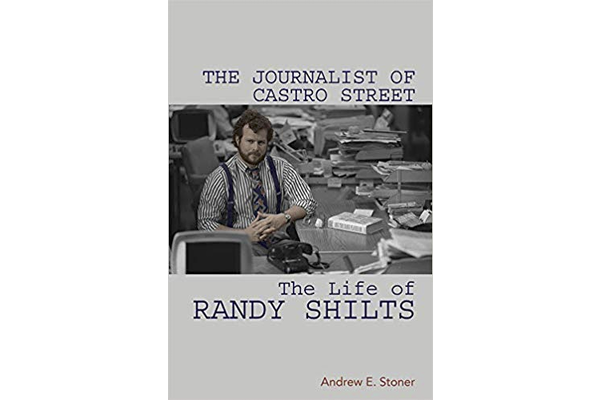

Writing about Shilts, someone I have grown to admire and love during more than nine years of research, required, however, more than just a tribute or formal canonization. After only a brief period of probing, one quickly finds that the legacy of Shilts remains a mixed one, depending upon whom one encounters. Many gay rights advocates laud his promotion of gay martyr Harvey Milk via Shilts’s first book, “The Mayor of Castro Street,” or his focus on the battle for lesbian and gay U.S. service members to serve openly in his last tome, “Conduct Unbecoming.” Others who fought the battles of the deadly HIV-AIDS pandemic that darkened America and the rest of the world reject praise and offer vocal and pointed criticism of Shilts as a heartless “Uncle Tom” of the gay liberation movement. These latter feelings flow directly from the praised – and scorned – work that won Shilts his most fame, “And the Band Played On,” and the portions of it resting on the idea of “Patient Zero” responsible for “bringing AIDS to America,” as the editors of The New York Post opined in 1987.

My research attempts to bridge these two shores, unearthing the incredible drive and determination of this outspoken gay man from small town Illinois, to becoming an early and important barrier breaker as an openly gay reporter for a major daily newspaper. Dead at the age of 42, a full 22 years before scientists would clear Shilts’s “Patient Zero” as clearly not the man who brought AIDS to America, the posthumous review of Shilts seems incomplete and unfair if it does not include a full review of all aspects of the journalist, author and man. There is value in taking up the lingering issues of how to place Shilts as a journalist and early gay liberation leader, and bring at least some resolution to the remaining conflict. We can do so without relieving Shilts of having to own his own words and actions, all the while placing them in context of his entire life.

The story of Shilts and the mixed legacy that remains a quarter century later has connecting points to our contemporary lives – where we seek a fuller understanding of historical people and times, but to do so in the correct context. Shilts’s story remains incomplete if we do not take in a fuller consideration of his successes alongside the problems centered primarily on his construction of the “Patient Zero” myth. Robbed of the living that could have resolved the dangling irritants in his story, we’re left with the same conflict Shilts felt as his life wound down. Similarly, we must wait the end of many stories playing out around us and perhaps find some resolution in the context time affords.